S.F. History Museum Highlights America’s First Immigration Restriction: The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882

It may come as a surprise to many Americans to learn that the first country to have its citizens specifically excluded by the U.S. Congress was not Mexico, or a Middle East nation, but China. In 1882, Congress passed the first of several Chinese Exclusion Acts that prevented all immigration of Chinese laborers. These laws were not reversed until 1943, when China was an important ally in the war with Japan.

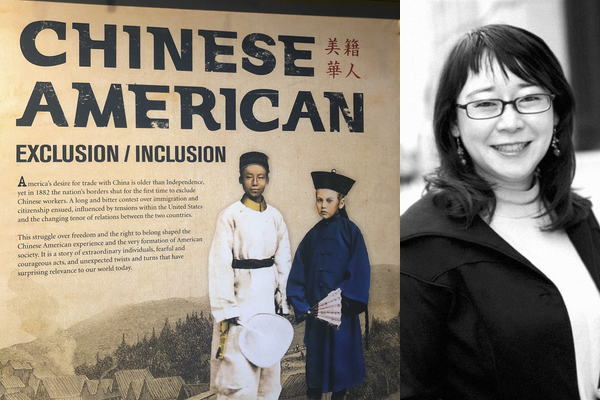

The Chinese Historical Society of America Museum (CHSA) is currently displaying an exhibit, Chinese American: Exclusion/Inclusion, which vividly documents the changing views of Americans towards Chinese immigrants in 19th and 20th century America. The museum, in the heart of San Francisco’s Chinatown, is the oldest organization in the country dedicated to the interpretation of the cultural and political history and contributions of the Chinese in America.

Tamiko Wong, the executive director of the CHSA, spoke with the History News Network about the exhibit. Before joining the CHSA, Wong was the Executive Director of the Oakland Asian Cultural Center. A graduate of U.C. Berkeley, she is a former Asian Pacific American Women’s Leadership Institute fellow. She has served on the California Commission on Asian and Pacific Islander American Affairs and is a recent graduate of Coro’s Women in Leadership program.

Q. The current exhibit is very timely. How was it organized?

A. Chinese American: Exclusion/Inclusion was originally curated by the New York Historical Society in 2014. Our museum provided content and paintings for the initial 2014-2015 show in New York. The NYHS originally hoped that the exhibit would travel to different parts of the country, but after one run at the Oregon Historical Society, the New York museum gave it to us in 2016. We were delighted because it is a high quality, interactive exhibition highly relevant to our story.

When it arrived in San Francisco, we added more objects from our own collection and refocused it to include more of a West Coast story. Although there are more than 5 million Chinese in America, we are still a small minority being only about 1.5% of the total population. Our hope for the exhibition is to enlighten visitors on the struggles of immigrants and contributions of Chinese in the U.S. even when citizenship was not an option. We want to contribute to the discussion of what it means to be an American.

The exhibit is timely because it clearly shows a pattern we have seen throughout history, not just in the US but elsewhere too. Immigrants are brought in as a source of cheap labor, and have often faced discrimination and harsh conditions. Especially during downturns in the economy, immigrants become scapegoats who are blamed for society’s ills. Racist rhetoric becomes normalized in the media, discriminatory feelings are codified into law, and immigrants face violence and unfair treatment. For Chinese Americans in particular, we have been seen as perpetual foreigners even when many of us are citizens, have fought and died for this country, and have contributed to the building of this country from everything from railroads to some of the civil liberties we currently have such as birthright citizenship.

Q. What has been the reaction to the exhibit by the local Chinese community and the broader, regional public?

Overall, Chinese American history is not general knowledge. Here in California, even though there are curriculum standards to teach about the Chinese Exclusion Act, I would say 90% of our new visitors know very little about Chinese American history prior to coming to the museum. So often we hear, “I had no idea about what the Chinese went through.” Those who took Asian American studies courses when they were in college may remember some aspects of our history, but the content which we cover in Chinese American: Exclusion/Inclusion is a very powerful history lesson on immigration policy, discrimination, and resilience. Visitors who leave messages in our comment books express how important it is to have this history shared and how timely it is because of how immigrant and racial issues are discussed today.

Q. Most of the exhibit materials were of American origin, including photographs, posters, newspaper clippings. Apparently very few written materials from Chinese immigrants (e.g. diaries, letters, books) have survived. Why is that?

I am not sure if the lack of first-hand accounts from letters or diaries is true of all periods in Chinese American history. The lack of letters and diaries is true in the case of Chinese railroad workers during the late 1800s. As reported by professor Gordon Chang, head of Stanford’s Chinese Railroad Workers in North America Project, despite an extensive search, researchers have been unable to recover first-hand accounts or letters from these workers although many could read and write Chinese. There are theories about why this is so, for example, many family and historical documents were destroyed during the Cultural Revolution in China. In the U.S., many Chinese communities were damaged or destroyed by hostile forces in the late 1800s-early 1900s. And the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire destroyed most of this city’s Chinatown.

Q. A large section of the exhibition is given over to the role of Chinese American women. One display noted that in 1850 only seven of San Francisco’s 4,000 Chinese residents were women. However, today in San Francisco, the city’s assessor and one of its seven supervisors are Chinese American women. What are the reasons for this dramatic evolution?

One current section of our museum, Towards Equality: California’s Chinese American Women is devoted to that topic. Unfortunately, this particular display will close in October.

To summarize, few Chinese women immigrated to the U.S. in the mid-1800s due to patriarchal norms in China that relegated them to their homes and reinforced their inequality. In the U.S. Chinese women were viewed as immoral, and Congress passed the 1875 Page Act that effectively stopped Chinese women from immigrating. The 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act curtailed the overall number of Chinese immigrants, but ironically created a broader opportunity for Chinese women to come as family members of merchants or American citizens. Over time, the population of Chinese women grew, especially among those born in the U.S. We find that these American-born, English speaking 2nd and 3rd generation women broke with traditional Chinese values and sought independence, mainstream acceptance, and became community activists seeking inclusion by American society.

Q. This year, 2019, is also the 150th anniversary of the transcontinental railroad, in which Chinese workers played an important part. One part of the exhibit notes that a delegation to the 1969 Centennial celebration was snubbed by Nixon’s Transportation Secretary.

I was proud to have been present at the transcontinental railroad’s sesquicentennial celebration held on May 10, 2019 in Utah (also known as Spike 150).

CHSA Board Emeritus, historian, and railroad worker descendant Connie Young Yu also represented CHSA at the Spike 150 celebration, and gave the opening speech. Connie’s speech paid homage to Chinese railroad workers and called for the reclaiming of the immigrants’ rightful place in history. Her presence at the podium fulfilled a mission begun in 1969 by then CHSA President Phil Choy. He was initially asked to speak at the centennial celebration, but at the last minute he was removed and replaced with actor John Wayne. To add insult to injury, Transportation Secretary John Volpe said in his keynote address, “Who else but Americans could chisel through miles of solid granite? Who else but Americans could have laid 10 miles of track?”

This was an insult to the memory of Chinese immigrants who actually performed these feats yet could not become citizens at this time due to racist laws.

Q. What are the next steps for the exhibit and the CHSA? Will this exhibit or others travel to other museums?

Chinese American: Exclusion/Inclusion has content that remains relevant and we plan to continue exhibiting it. We hope to add more content that helps to tell the important and timely story of how immigrants have been treated here in the U.S. through different points of view. We hope to add features that will focus on how the lives of well-known Chinese Americans who have intersected with history, looking at immigration to the U.S. that has been mediated by experiences in other places such as the Philippines, Latin America, and Taiwan.

The overall exhibition is large and this makes it difficult to travel. However, we have built a number of traveling exhibitions that touch upon the themes covered in it. The most travelled exhibit to date is Remembering 1882 which focuses on the Chinese Exclusion Act and this year, because of the 150 Anniversary of the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad, our The Chinese and the Iron Road: Building the Transcontinental has been very popular. Additionally, starting in October, our exhibit Towards Equality: California’s Chinese American Women will be available to travel and we welcome inquiries from other institutions who may wish to show it. In addition, we have available another display, Detained at Liberty’s Door, which traces the formation of the Angel Island Immigration Station in San Francisco Bay and highlights the inspiring story of Mrs. Lee Yoke Suey, the wife of a native-born citizen who was detained for more than 15 months.

Note: to see excerpts from the exhibit and learn more about Chinese Historical Society of America, go to www.chsa.org., You may contact the museum staff at info@chsa.org.