These American Political Bachelors Were Known as ‘Siamese Twins’ During the Antebellum Era

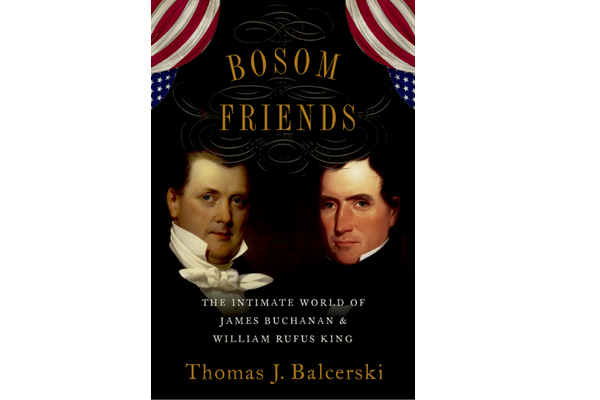

Thomas J. Balcerski is an Assistant Professor of History at Eastern Connecticut State University and the author of Bosom Friends: The Intimate World of James Buchanan and William Rufus King, an original dual biography. He received his PhD in history from Cornell University in 2014.

Why did neither James Buchanan or William Rufus King ever marry? They were lifelong bachelors. And how unusual were they for not getting married?

Bachelorhood was not uncommon during the 19th century, particularly the early part of that period. In fact, during the 19th century, the prevalence of bachelorhood grew, such that, in a place like New York City, it had reached an all-time high of perhaps 12% of the male population.

Bachelorhood as a phenomena was very much part of the culture of the period. When you look at the United States Congress during this period, particularly the US Senate, I ran an analysis between the years 1790 and 1860 to estimate just how many men were unmarried and I determined the number to be at 7%, with perhaps as many as 4% being lifelong bachelors. On the whole, bachelors were a known part of politics. The question becomes partly a biographical one: Why did each man marry or not? And I say that because of that percentage of bachelors, many would go on to marry after their service in the Congress had ended. James Buchanan and William Rufus King, in contrast, never married and this does set them apart from others with whom they served and lived in a boardinghouse, and even politically for the period, they were the most prominent bachelor politicians of the 19th century.

Another word about why each did not marry: I do think both men were very ambitious. For bachelors, the decision to marry or not was very much based on how it might affect one's future course, whether it be in one's own career or personal life. For political bachelors, there was an additional calculation of whether or not marriage would impede or enhance one's political standing, and in those cases, Buchanan and King calculated that they could achieve political success without marriage. That is not to say that either man did not engage in courtship, or at least purport to engage in courtship, but it is to say that at a certain point in their political careers, they had learned to identify as bachelors and to take the good and the bad that came with it.

How did the historian Elizabeth Ellet come to remember the two men as ‘the Siamese twins’ and how have they been remembered since?

Elizabeth Ellet is a writer, a historian, and a contemporary of many of the politicians of the 19th century. She personally knew several of the former first ladies of the period, and was at least on corresponding terms with them. One whom she corresponded with: Julia Gardiner Tyler, who was the second wife of President John Tyler. Note: John Tyler was widowered in office while President and remarried to a much younger Julia Gardiner. In the 1860s, when Elizabeth Ellet was preparing a history of what she called The Court Circles of the Republic, she reached out to Mrs. Julia Tyler and asked for her reminiscences about her two years as the First Lady and wife to President John Tyler. It's from that correspondence that I find the phrase "the Siamese twins" enters into historical memory, by way of a First Lady looking back at the boardinghouse culture of the period. That's why I began the book, with Ellet's recollection as a way to suggest both how memories are made and how historians have played a part in characterizing the relationship of Buchanan and King.

I did want to add that in addition to Julia Tyler, Elizabeth Ellet wrote to Harriet Lane Johnston, who was the niece of President James Buchanan and who served as his First Lady. Additionally, she wrote to Cornelia Van Ness Roosevelt who, as I discuss in the book, plays a critical role in bringing together King and Buchanan at a moment when they had separated upon King’s departure to France in 1844. Mrs. Ellet certainly plays a role in my story and I think it's a fitting one, to begin with a contemporary historian looking back at the period before the U.S. Civil War.

Your book argues that Buchanan and King’s relationship conformed to an observable pattern of intimate male friendships prevalent in the first half of the nineteenth century, meaning they were not America’s first gay Vice President and President. How did you arrive at this argument?

That's a great question in that it connects the argument I'm making about friendship with questions of sexuality, and particularly, modern understandings of it. I think though in your question, just to push back a little bit, is something of a conflation that I don't quite want to make. And that is to say that intimate male friendship is a construct that can be observable to the 19th century. The word ‘intimacy’ is the key word here. I'll begin with that.

Intimacy is a word of the period. I find it in the correspondence of politicians, particularly people serving in the Congress. What it had connoted to mean was a closeness, not so much in a physical sense as much in a political, and to a lesser extent, personal sense. We get this phrase — personal and political friendship.

For James Buchanan, he distinguishes these two things. When they combine, however, that is when intimacy seems to enter into the equation for him. In parsing his correspondence, I tried to see about whom he spoke of as an intimate friend—and there were several besides King. King, of course, is in that category and so it's not to say that there wasn't a more deeply intimate friendship compared to some of the others, but it does fit into a pattern, not just of Buchanan, but as I say, across the 19th century. The notion of sexuality and the notion that they are or are not gay does take us down a different path, and one that I think is what may draw readers to the book, and for that, I'm grateful.

At the same time, in the introduction of the book, I talk about my assessment. The evidence does not permit a definitive rendering of their relationship as anything other than platonic, but it also allows me to suggest that we move beyond the question of modern terms related to sexual identity and orientation. We can and we should, as historians and biographers do, since interested readers want to know as much as we can about the outlooks and attitudes of these two men.

For that, in my own mind, I've come to see Buchanan as someone actually quite different from King. I see them as almost on opposite ends of that spectrum, with Buchanan more clearly conforming to romantic courtship with women, and King not as much. In their relationship, then, I see much more of a one-way desire, attraction, and longing, that of William Rufus King for James Buchanan, than I see in return. For that reason alone, they should not be figured as a gay couple, and even if one wants to use the orientations of today to understand either or both men, I don't think it necessarily answers the question of their relationship as much as it perhaps can be a satisfying exercise in understanding historical sexuality.

Can you talk about the period of their active friendship, split into two discrete phases, and spanning more than 18 years, as the most successful example of a domestic political partnership in American history?

Yes, and to begin with that notion, 'domestic', I think it's important to remind readers how boardinghouses and boardinghouse culture worked in the 19th century. Prior to the period in which Congress met continually, more or less, with short recesses, during a two-year term, the Congress is typically only in session for three periods of the term, so that the typical Congress would spend less than a year of the 2-year term in Washington. The seasonal nature, therefore, of Congress required a different kind of residential pattern than what we see today in Washington, D.C. They instead shared temporary establishments or boardinghouses or messes. They lived there, they often took meals there, and in the process became, well, domestically intimate with one another.

We see that across multiple boardinghouse patterns, not just Buchanan and King. Buchanan and King, though, were somewhat different than the typical boardinghouse group. For one thing, they shared the same Democratic party affiliation, but for another, they came from different sections of the country. In my study of the boardinghouses of the 19th century, it's a rare thing to find men from different parts of the country living together for so long a period.

They might come in and out for one or two sessions of the Congress. When you look at Buchanan and King, and you realize that they lived together for 10 years in Washington, D.C.—something else then was at work than mere convenience. That's when we come to the point that they self-consciously lived with one another because they were bachelors. My findings suggest that they thought of themselves, to use their words, as a "bachelor's mess," and they brought in other bachelors with whom to live. During that 10-year period, it wasn't just Buchanan and King, it was actually a rotating cast of characters, most of whom were unmarried.

The second period of their friendship—you are right to call it two discrete phases—is after they are no longer living together, and in some ways, the second period is more poignant but more important. Poignant in that they lose the intimacy of their friendship. They are now separated and no longer living together. Important and significant in they both begin a rise into national power which ends with their election to high office. There is a lesson here, too, that for Buchanan and King, each man did need to leave the other in order to eventually achieve success on his own. They tried and failed to be on the same ticket for President and Vice President. Only separately, then, were they able to obtain that office.

As you wrote, Buchanan and King were different: they had varying socioeconomic statuses and were of opposite political parties. But they also shared some personal factors in common.

To start with, it is unusual that two men from different parts of the country and who began with different political views would ultimately run on the same ticket. To understand why, we must first remember that Buchanan and King were born during what's called the First Party System which consisted of, on the one hand, the Federalist party, and on the other, the Democratic- Republican party. Buchanan was a Federalist. King was a Democratic-Republican.

Buchanan, therefore, had certain views about banking, the tariff, and the war, which King held in opposite. When Buchanan was first elected to the US House of Representatives, he was a Federalist. King, a Democratic-Republican. Politically, they came from a different background; personally, too, they came from different socioeconomic standings and cultural backgrounds. Buchanan was born fairly poor in a log cabin. His family was involved as merchants and traders along a route in what is today Mercersburg, Pennsylvania. He was one of many children, the first of which to go to college, and did not have much in the way of material wealth. He made it on his own as a lawyer in the city of Lancaster, which was then the capital of Pennsylvania before it moved to Harrisburg.

William Rufus King was born into a large slaveholding family that was prosperous and that grew agricultural products like wheat, corn, and cowpeas in North Carolina. He inherited land and slaves from his father when he turned of age, and he too went to college and studied law but had an easier go of it and got into politics at an early age as a result. He was a Democratic-Republican, so he supported the War of 1812. He stood against the banking system and against tariffs which generally protected manufacturing concerns in the north at the expense of agricultural concerns in the south.

The great change in politics during this period can be summed up in one person: Andrew Jackson. Buchanan realized the force of nature that was Jackson and shifted his political allegiance towards him. King naturally merged into that direction as well. Buchanan probably, of the two, moved further in his political principles than King, but they both fell into line as Jacksonians. By the time, therefore, each comes to the US Senate—Buchanan comes later than King—the Jacksonian orthodoxy was fairly well-established. They more-or-less would follow it for the rest of their careers.

One man from Pennsylvania, part of the North, which was moving away from slavery. There were still enslaved people in Pennsylvania after Buchanan was born. Emancipation laws would go into effect gradually. King will hold to the slaveholding system for his whole life, and in fact, it becomes the key issue on which Buchanan must bend for a political alliance with William Rufus King to work. In time, Buchanan will come to see the political value of protecting the slave system from his interactions with Southerners such as King.

You wrote that “the heart of the friendship of Buchanan and King lay a solemn pact, developed in the boardinghouses of Jacksonian Washington, that the Union must not split over the question of slavery.” How did the two men cultivate this pact?

I still stand by that statement and yet the evidence for it is more circumspect than direct. Let me try to give some examples of how I came to that conclusion. The one gets back to the very nature of a boardinghouse friendship. Buchanan, it turns out, was the only Northener in the boardinghouse called the bachelor’s mess. All the other men who came into it—unmarried men—were Southerners. Indirectly, you see that Buchanan is the one who has to adjust himself culturally to his messmates' belief system. That's one piece of evidence. The second piece comes in with the voting patterns that Buchanan took and his speeches in the US Senate during this period.

We find evidence of him, whenever possible, supporting repression or gagging discussion about the issue of slavery, and Buchanan is famously the author of the United States Senate gag rule forbidding any petition that would call for the end of slavery in the south. He put his money where his mouth is, you might say, politically. The third way we see it is just in how as President, and even before that in retirement, he lives the life of a cultivated southern gentleman at his estate in Lancaster called Wheatland. Then, as President, we see it in his policies through his support of the Dred Scott case, his support of the Lecompton Constitution which permitted slavery in the Kansas territory, and arguably by his less than hardline stance in the face of Southern secession in the winter of 1860 and 1861.

Finally, too, Buchanan preferred the company of Southerners while President, and this is what's fascinating for me: One of his favorite people to have in his White House was none other than King's niece, Catherine Ellis. We see evidence of her at multiple points of Buchanan's term as President, including in a portrait that was painted to commemorate President Buchanan's visit with Prince Edward Albert to Mount Vernon to see the tomb of George Washington. It's been little noticed but Harriet Lane, his niece—and First Lady—stands directly next to Catherine, King's niece.

The term ‘bosom friendship’ meant a particular kind of domestic intimacy common in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Are there any other early American phrases that have caught your attention during the making of this book?

You mentioned ‘Siamese twins’ earlier, and initially, I had thought that that would make a more apt title for my book, in that Elizabeth Ellet’s evocation of Buchanan and King as Siamese twins seems so nicely to capture the political meaning of their friendship. Why I chose ‘bosom friends’ and why I think it stands out among the various phrases and euphemisms used in the 19th century is that it connoted more positively. It allowed for something of that personal nature to be understood in their friendship. It was, of course, political, but people understood that they had a personal connection as well.

We find the phrase being used about a number of political duos of the period, that include some of Buchanan and King's greatest enemies and critics. Towards that end, I would add to the various a list of phrases, such as Siamese twins and bosom friends, a few others that had entirely to do with political gossip from the period; words that were used to describe Buchanan and King in various stages. I'm thinking here of the phrase 'Aunt Nancy' or 'Aunt Fancy' or 'Miss Nancy'. All three of them show up directly in their correspondence, newspapers, talking about either Buchanan or King.

Deciphering gossip actually became a big part of my project, trying to think about the kinds of insults that were used. When we think about our own political times and how gossip and insult works, it's not a foreign concept to us. What's perhaps more interesting here is these series of 'aunt' insults do have a gender implication that tends to belittle and feminize them. For that reason, historians of the period have been attracted to them. They've often pointed to Andrew Jackson using the phrase 'Aunt Nancy' to describe Buchanan and King as somehow definitive proof of a sexual relationship. I always point out in return that it’s just one piece of what historians call ‘a grammar of political combat’, and that Buchanan and King, for their part, also used such gossip and language to talk about their political opponents.

It is a world that requires us to almost dial back a little bit our modern assumptions about what words mean, and instead try to think about what nineteenth-century people thought of.

Many factors contributed to the lasting power of their relationship, but as you describe “its ultimate longevity may be attributed to another factor altogether: their nieces, Harriet Lane Johnston and Catherine Margaret Ellis.”

It's important to remember what happens after a great man dies, and that a President of the United States in the 19th century was not given any special treatment or given government attention like he would today. Like it or not, at some point, the papers and letters and artifacts from the presidency of Donald Trump will end up under National Archives and Records Administration control, as it has since the time of Herbert Hoover. Before President Hoover, no President was given that Federal support and apparatus. We find that with someone like Buchanan, his personal papers became then part of the obligation of his familial descendants.

Harriet Lane Johnston was an incredible lady and a dogged advocate for her uncle during the remainder of her life, and she will help to establish the collection that ends up at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, as well as at the Library of Congress, both of which today are very important to understanding the life of James Buchanan. By contrast, Vice Presidents receive even less attention and support, and there are some US Vice Presidents about whom we know almost nothing because their papers do not survive.

William Rufus King is in that category to a degree. His letters to other people show up in personal papers throughout the country, but the letters that he received are fewer than you might expect. There are possible explanations as to why Buchanan's correspondence is so large and voluminous, and why King's is not, but at baseline, it has to do with the circumstances of their families' lives after their respective deaths. Lancaster, Pennsylvania avoided the scourge of the Civil War. Selma, Alabama was among the last of the major battles in 1865. We know from the history of the battle of Selma that King's plantation was raided and valuable articles and items were destroyed, and that it is quite likely that personal papers were destroyed in the process.

However, there's other explanations for the asymmetry in their papers, and I talk about that in the book. What I want to stress here is that these two nieces were incredibly proud having been at their uncles’ sides during their lifetimes and were even more doggedly devoted to preserving their legacies.

There is a myth—a persistent myth—that the two nieces, by prearrangement, destroyed their uncles' correspondence. My book helps to dispel that myth. If anything, it's because of these two nieces that we have surviving correspondence of their uncles. More than that, the correspondence between them reveals a different kind of intimate friendship. That between two women who shared something in common: in being at the scene of high political power in the 19th century, something that women were only rarely exposed to during that period. As such, they maintained a lifelong friendship as well.

From a historian's research standpoint, when you approach archives, you encounter many letters. Are you hoping for as much as possible to draw primary research sources from, or are you sizing up the collection? How do you size up and scope that in order to execute a book, dissertation, or project?

I took the approach of anything written by William Rufus King was valuable, and because we unfortunately do not have all that much, it proved to be the case. James Buchanan, on the other hand, is a different story. I spent much of the last several years reading as many of his letters as possible, and even so, I have to admit, I didn't get through them all. We are fortunate that archivists and librarians have prepared detailed finding aids which allow us to understand the ebb and flow of the collection, but more importantly, for Buchanan, we are fortunate (and I was extremely so) to be able to work from historiography in past histories and biographies. I'd like to point out that in Buchanan's case, Philip Klein wrote the definitive biography of James Buchanan, published in 1963.

I had a chance also (and this is something I might give as a piece of advice) to look at historian Philip Klein's own personal papers, that upon his death in the 1990s, he donated to Pennsylvania State Library where he worked during his career. Reading Klein's notes and papers was an incredible experience. It made me realize that if Klein covered it, he did so accurately, and that part of what I hoped to do was build upon Klein to see areas he might have missed, to find new sources that would have come to light since the 1960s when his book was published. Also, to use the interpretive framework that I knew I was bringing in the 21st century which he didn't have in the mid-twentieth century.

To your question, yes, it is sometimes valuable to be selective when looking in an archive, but as a biographer—and in my case a dual biographer—everything is on the table. We need to be open to as much as possible, following sources where they lead us.