Is Donald Trump a Conservative?

In December of 2015, Senator Lindsey Graham asked rhetorically, “You know how to make America great again? Tell Donald Trump to go to hell”. Graham went on to say that President Trump “doesn’t represent my party. He doesn’t represent the values that men and women who wear the uniform are fighting for.” Although Graham was among the most outspoken critics of then candidate Trump, he was not alone in this criticism. Ted Cruz and other prominent Republicans warned against a Trump presidency and feared that his beliefs contradicted that of their party.

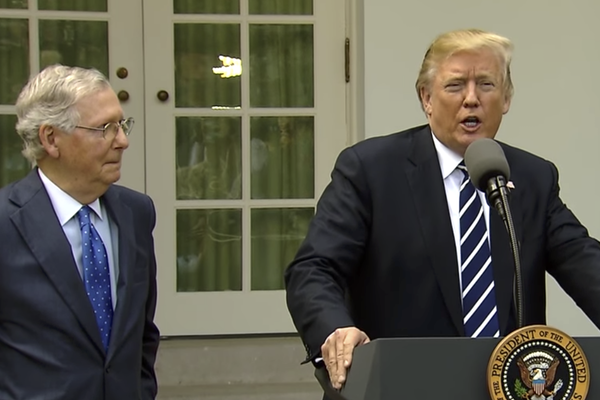

As Republicans are now nearly united in defending Trump from impeachment, it is hard to remember that just a few years ago Republicans routinely criticized the President. But it’s worth examining why many Republican leaders initially resisted Trump’s primary bid. Trump’s policy interests and approach to politics deviate from the modern conservative movement.

It is impossible to separate the overlap between conservatism and the Republican party because it has most traditionally served as the philosophical inspiration of the party’s members. For intellectuals, pundits, and mainstream voters alike, conservatism has long been a concrete metric by which to judge a Republican candidate.

That is not to call conservatism a one size fits all philosophy. As historian George Nash explains, conservatism is “a coalition with many points of origin and diverse tendencies”. In other words, conservatism is a broad movement that encompasses a wide range of intellectual beliefs that are relatable but not identical. Nevertheless, Republicans are generally expected to agree with a few aspects of the conservative coalition: free trade, small government, and individual freedom. So, does Trump – the often touted unique, unprecedented President – fit the aspects of modern conservatism?

In large part due to George Nash’s book The Conservative Intellectual Movement in America Since 1945, historians are able to concisely define modern conservatism. Nash conceptualized that there were three coalitions that formed the conservative base after the Second World War. The first were classical liberals – outraged at the New Deal – who feared that individual liberty was disappearing. The second coalition was comprised of traditionalists who were angered by the rise of totalitarianism and advocated for an awakening of religious orthodoxy. This sect, according to Nash, were militant evangelists who hoped to preserve the integrity of America and the western world through the renaissance of traditional values. The final group were former communists themselves who feared the power of the party. The so called “ex radicals” fought fervently against the spread of communism. Together, these three separate coalitions formed the modern conservative movement that influenced American politics throughout the Cold War and into the twenty first century.

Of course, there were always natural tensions and divisions within the coalition. However, the divide began to worsen as the Cold War ended and the spread of Communism, a decisive factor that kept the coalition together, faded. In addition, the spread of globalism and mass migration has had a profound impact on all political philosophy of the 21st century. According to Nash, these two events led to the rise of populism internationally because new conflicts filled the void left by the conclusion of the Cold war and globalism has led to a counter movement of nationalism. Populism, of course, can and has existed on both sides of the political spectrum. As a result, it is both unfair and incorrect to prescribe populism as the influence that changed conservatism.

So, does Trump fit the mold defined by historians on conservatism? Does his brand of populism even fit the classical ideology of conservative populist thought?

Not entirely. While it can be argued that Trump stands for the general three beliefs of conservatism – individual freedom, the suppression of authoritarians, and a return to a “traditional” lifestyle – that is also the jargon of all political leaders, despite the consequences or intentions of their actions. In addition, conservatism is more than just those buzzwords – it is a complex ideology that includes theory and policy. Therefore, it is unfair to fit Trump as a conservative because of these three general beliefs. And, most importantly, Trump greatly differs from conservatism in two main ways: his rejection of globalism and his incessant attacks on all intellectual elites.

Globalism and free trade have been a basis for conservatism since the philosophical movement gained popularity. It has historically been so important that movements, organizations, and publications have assembled to tackle free trade economic issues. Most famously, the traditionally conservative Economist publication was started to organize against the English Corn Laws in 1843 – tariffs that harmed the English economy.

In the more recent past, conservatism has promoted internationalism to preserve and promote western institutions. The internationalist movement is well documented and is rooted in the philosophy that America must promote freedom by working with other nations regardless of the inherent cost.

In addition, recent conservatism has promoted free trade globally. Conservative presidents Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush each supported regional trade agreements with Mexico and Canada and Bush 41 started the NAFTA negotiations. Free trade and globalism were a standard platform of modern conservatives.

But President Trump supports none of these ideals. Rather, he advocates for tariffs not unlike The Corn laws the Economist lobbied against. He argues that NAFTA is harmful to the United States and that we must rethink our involvement trading with our neighbors. And finally, he withdrew the United States from a similar trade agreement, the Trans-Pacific Partnership, because of his beliefs against free trade.

Even beyond his economic policies, President Trump is by no means an internationalist. Rather, he is most identifiable as a nativist – a fervent nationalist who supports only American interests. While traditional conservatives were concerned with the wellbeing of the western world, the current president is concerned only within his own borders.

And finally, rather than coalesce against dictatorships – a trait Ronald Reagan was so widely praised for – he is friendly and congenial with the leadership of both Vladimir Putin and Kim Jung-un. It is common, factual knowledge that their governments do not promote freedom, democracy, or individual liberty. But president Trump – unlike modern conservatives – does not care.

Donald Trump hardly fits the definition of a conservative when analyzing his policy beliefs. Perhaps what’s most shocking, though, is that he doesn’t seem to care. In fact, he actively tries to not be a classical conservative. Modern conservatives have banded together, worked as a coalition of intellectuals who agree on a philosophical basis. President Trump is not interested in doing so. Rather, he claims his movement “is about replacing a failed and corrupt political establishment” because it “has brought about the destruction of our factories and our jobs”. President Trump clearly has a political vendetta against any intellectual organization.

Importantly, he claimed that nobody has a better understanding of the American system, and that “I alone can fix it”. Trump’s claim of individual power is important to note because he establishes himself as a singular unit of change rather than a leader of a larger philosophical coalition. Conservatism has long been understood as an alliance of individuals who share a common interest. But Donald Trump wants to be an individual – separated from the intellectual movement – and seen as the individual source of knowledge and change.

Anti-elitism is not new in politics and it exists across the aisle. Throughout American history populists have attacked and blamed elites for their respective political qualms. According to Nash, though, they often target a select, identifiable group of people: a republican populist would blame the liberal elite and vice versa. But president Trump blames every elite – conservative and liberal alike. This again separates president Trump from the traditional conservative movement.

Further, modern conservatives have been blatantly elitist. Mitt Romney, the previous Republican candidate for president, stated that he would never win over 47% of the country because they pay no taxes. This claim to wealthy donors perfectly highlights the blatant elitism that conservatism has often aligned with. Newt Gingrich, former Speaker of the House, ranted about Steve Bannon – a Trump friend and former Chief Strategist – for his attack on the GOP establishment. Gingrich stated that starting a political war against the Republican party was an “absurdity”. Two former symbols of conservatism have been blatantly elitist and highly critical of Trump’s anti-elitism. By diverging from the GOP established leaders, Trump proves to be outside the conservative spectrum.

Perhaps what is most interesting is not Trumps sense of anti-elitism, but the irony in his rhetoric. Trump clearly claims to be anti-establishment but is himself is so enshrined in elitism. He often promotes himself as successful and knowledgeable because of his elitism, his wealth, and his luxurious lifestyle. Populists most often try and cast themselves as distinct from elites – Bernie Sanders, for example, portrays himself as outside the wealthy elite. Whether or not that is true is beside the point: the irony is that Trump casts himself as the elite while simultaneously branding them as evil.

Trumpism promotes taking down the infrastructure of intellectual establishments. These groups and set on opposing him as well, regardless of political affiliation. For example, the National Review, Commentary, and The Weekly Standard each oppose President Trump in obvious and outspoken ways. The Weekly Standard went as far to issue a plea for an entirely new brand of conservatism. The National Review, started by the conservative intellectual William F. Buckley, even published an article titled “Against Trump”.

It is clear that the conservative establishment does not view the president as one of their own. The three main publications have regularly criticized the president. Rather than endorsing a republican president’s actions, traditional publications actively resist him. Conservative politicians once longed for the endorsement from such intellectually respected publications known for promoting the wellbeing of their philosophical beliefs. But no longer.

President Trump’s mutual alienation from the classical conservative ideology shows that he does not support them, and they do not support him. This, combined with his policies that outright defy what modern conservatism stands for, lands him outside the understanding of modern conservatism.