Is There Anything Left to Learn about Hitler?

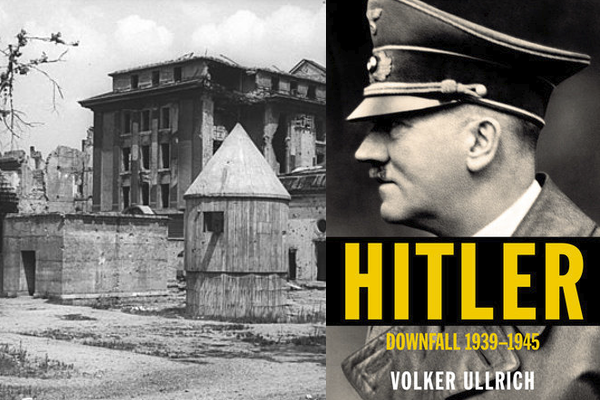

Reviewed: Hitler: Downfall 1939-1945 by Volker Ullrich (Trans. Jefferson Chase, Alfred A. Knopf, 2020)

Is there anything new we can learn about Adolf Hitler?

More than 128,000 books have been written about the dictator, including acclaimed biographies by historians Richard Evans, Alan Bullock and Hugh Trevor-Roper. However, pieces of new information continue to surface (e.g. diaries, archives) and each passing year provides authors with a different historical perspective on the perpetrator of the “greatest crime in history.”

As Volker Ullrich notes in the closing pages of Downfall, “we are not and cannot be done with confronting Adolf Hitler. In a certain sense, we will be bound to him for all eternity.”

Ullrich is a highly respected German journalist and in this, the second of his two-volume biography of Hitler, he has wisely chosen to focus less on the what than on the why and how of the dictator’s crimes. In particular, he focuses on two of Hitler’s most deadly undertakings: The Holocaust and the disastrous invasion of Russia.

Although Hitler publicly railed against the Jews countless times in his 12 years in power, he was careful never to issue any written instructions ordering their mass extermination. In Downfall, Ullrich concludes that before 1941, Hitler’s initial inclination was to simply remove Germany’s Jews to a distant location. The dictator considered North Africa and the island of Madagascar as possible sites for relocation, but dropped those sites after signing an armistice with Vichy France.

Hitler also believed Germany’s Jews could be used as bargaining chip in negotiating with President Franklin Roosevelt, whom he considered “a dupe” of Jewish capitalists.

December 1941

Ullrich points to two key events in December 1941 that changed Hitler’s mind about the fate of the Jews. First, his drive into Russia stalled outside Moscow. This dashed his hopes for a swift conquest of the Soviet Union and ruled out mass relocations of Jews deep inside Russa. Second, on December 9, Germany declared war on the United States. With that action, Ullrich notes, “any calculations that the Jews could be used as bargaining chips to keep America out of the war were now obsolete.”

This led to the infamous Wannsee Conference of January 20, 1942, where Nazi party leaders and SS commanders including Adolf Eichmann and Reinhard Heydrich plotted the mechanics of the Holocaust. These ambitious bureaucrats operated without any specific orders but with “a clear signal” from Hitler and SS commander Heinrich Himmler that the mass extermination of Europe’s Jews must now be carried out as quickly as possible.

In the next three years, as the killing machine swung into action, Hitler received verbal briefings, but was careful not to take direct responsibility. For example, in late 1942, the SS made a boastful documentary about its mass killings, but Hitler declined to see it. His preference was for “keeping at a distance the reality of the genocide he had set in motion.”

Declaration of War on U.S.

Ullrich addresses one question that American historians have long wondered about: Hitler’s decision on December 9 to unilaterally declare war on the U.S. At that point, Congress had declared war on Japan, but not on Germany; FDR intended to fight Germany, but hadn’t yet formally declared war.

The Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor came as a complete surprise to Hitler. Initially he was “overjoyed,” believing it was a great opportunity for his war effort. Greatly underestimating American military capabilities, he thought the U.S. would be consumed by fighting Japan and be forced to cut back supplies to Great Britain and the Soviet Union.

He also saw his declaration of war as a major propaganda coup because “a major power does not wait for the enemy to declare war on it.”

Many historians have wondered if Hitler might have possibly won World War II if he better managed Germany’s economy or deferred to his generals on military strategy. Ullrich believes that Hitler sealed his fate when he invaded Poland. That immediately triggered Great Britain’s entry into the war and set up an inevitable confrontation with the Soviet Union and the U.S., two world powers that Nazi Germany would never be able to defeat.

Downfall describes how the leading German generals were always afraid of Hitler, and shows how the June 20, 1944 attempt to assassinate Hitler was flawed in conception and doomed to fail.

Ullrich believes that Hitler’s “six years of absolute power (1933-39) had a pernicious influence on the dictator’s personality.”

He adds that “his egocentrism, his inability to self-criticize…his tendency to overestimate himself, his contempt for others and his lack of empathy…” all increased, making him a fanatical tyrant divorced from reality who was willing to destroy his own nation along with himself.

In considering the responsibility of the German people for Hitler’s crimes, Ullrich concludes that Hitler’s 12 years in power were a “dictatorship of consent.” The Nazi leadership was successful in reducing unemployment, improving social welfare programs and keeping taxes low. And, of course, the Nazis maintained a brutal police state. Thus, the majority of Germans accepted Hitler with little dissent, until the Russian armies steamrolled across the eastern border. Only then did the populace tear down their Hitler portraits and burn their Nazi party cards.

Judgment

As far as the Holocaust, Ullrich states that while “few Germans knew everything about the ‘final solution,’ very few knew nothing about it.” Although the Nazi propaganda machine was careful never to discuss the Holocaust directly, the average German could not help but notice that all the nation’s Jews had disappeared without a trace, their property confiscated. German citizens also heard whispered accounts of atrocities from soldiers on leave from the eastern front.

In his concluding chapter, the author calls for a continuation of the “German culture of self-critically examining the past.” This is essential to combat a small group of neo-Nazis in Germany (active on social media) who deny the Holocaust and seek to remove memorials about it.

Ullrich warns that if Hitler’s dictatorship “teaches us anything it is how quickly democracy can be prised from its hinges when political institutions fail.”

In this contentious (and not-yet-completely-finished) election year of 2020, that is a lesson that American readers can take to heart.