Biden's Inaugural and the Return of History

Four long years ago, newly sworn-in U.S. President Donald J. Trump promised unprecedented achievements. It was a speech bereft of history, promising to overcome past problems—invoking crime, rusted factories, and jobs exported overseas—with unprecedented methods, in order to return to a mythic past that never existed. “We are looking only to the future,” Trump said, promising America would be filled with “winning like never before.” In a repudiation of establishment politics, he vowed to accomplish them by handing power back to the people. Trump called his followers “a historic movement, the likes of which the world has never seen before.”

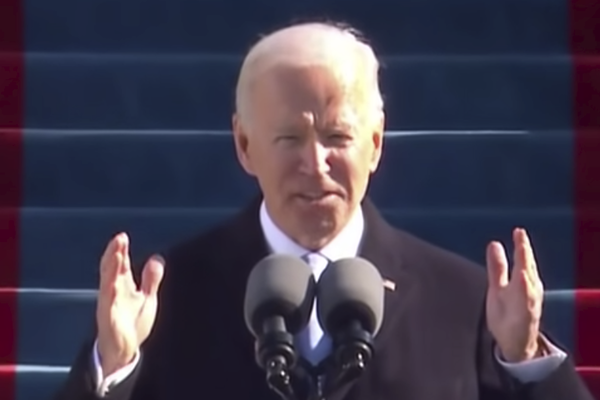

Joseph R. Biden, inaugurated on Wednesday as the nation’s 46th president, echoed some of Trump’s calls for unity and national renewal (as most inauguration speeches do). But there the similarities stopped. Instead of finding a new way to combat yesterday’s issues, Biden showed an understanding of how history can be applied to solve the problems of the present—the pandemic, inequality, racism, financial insecurity, and environmental degradation. Rather than harkening back to America as a finished product left to rot, Biden urged Americans to continue building this unfinished project we call the United States.

As Biden—and his speechwriting team, including the historian Jon Meacham—realizes, there is no magical way to build toward a better future. “I know the forces that divide us are deep and they are real,” Biden said. “But I also know they are not new.” It takes hard, painstaking work, using tried-and-true methods like clearly written yet expertly crafted legislation, guided through Congress with compromise and deal making. It is done by respecting norms and traditions in the ways the legislative and the executive branches of government conduct their business.

The president, as well as legislators and political appointees, accomplish goals—whether they believe in “small” or “big” government—by dedicating themselves to the task at hand: governing the country by making and enforcing its laws. A rededication to good governance might be a way to overcome the increasing polarization that has wracked the country for the past three decades. It allows for dissent without making politics a zero-sum game focused on power rather than a common goal. As Biden eloquently put it: “Politics need not be a raging fire destroying everything in its path. Every disagreement doesn’t have to be a cause for total war.”

It is no coincidence that the president’s next words took aim at Trump’s assault on truth, a call to “reject a culture in which facts themselves are manipulated and even manufactured.” Making up facts about past and present fueled the rise of the conspiracy theorists who attacked the Capitol, believing in the Big Lie: that the election was stolen, either through massive voter fraud or an illegal plot to rig the election by changing voting methods.

Trump and his supporters (and not only the conspiracy theorists) view the past in heroic terms. The past is to be used to inspire Americans to be proud. It must be conserved, like a tiny, pristine ship in a bottle—devoid of context. And so a statue of Robert E. Lee represents not a snapshot in time of what people wanted to believe when they erected it, but a universal truth to stand for all time. Then destroying statues can be equated with destroying history. Trump hoped to erect a garden of national heroes, an eclectic list of American personalities, more appropriate for a wax museum than a sculpture garden. Ultimately, the garden of heroes was not about history because it was not meant to instruct but to elicit pride.

Another of Trump’s last acts as president was to publish the findings of the 1776 Commission, a body ostensibly about history but really another exercise in pride conservation. The job of the commission was to respond to New York Times Magazine’s 1619 Project, which puts slavery at the forefront of America’s founding. The 1619 Project—like any historical work—is not above criticism or without flaw, and several prominent historians have spoken out against it. Rather than collecting a group of historians to produce a more nuanced and contextualized history that might explain and rectify the 1619 Project’s flaws, however, Trump convened a group of political loyalists—none of them specializing in the history of the American Revolution. It was no surprise, then, that the commission’s report was not a work of history, but a flimsy, fact-bending and citation-free critique. It is meant to inflame and attack, but produces no way forward. Having vanquished uncomfortable facts, what were Americans to do, their chests puffed with all this pride?

We must puncture our own bubbles of pride, within which people of all political stripes have ensconced themselves. History can be the needle—a way to end this “uncivil war,” as Biden called it. Why? Because history done right provides citizens and policy makers with what historian Francis J. Gavin has called a “sensibility,” made up of all the antidotes to our current malady that Biden invoked. Empathy. Humility. Understanding. One of Biden’s first presidential orders will disband the 1776 Commission (the report itself has already disappeared). It is a sign that the U.S. presidency, and hopefully the rest of the government, is rededicating itself to learning from history, rather than making it up whole cloth.