Political Violence: Still as American as Cherry Pie

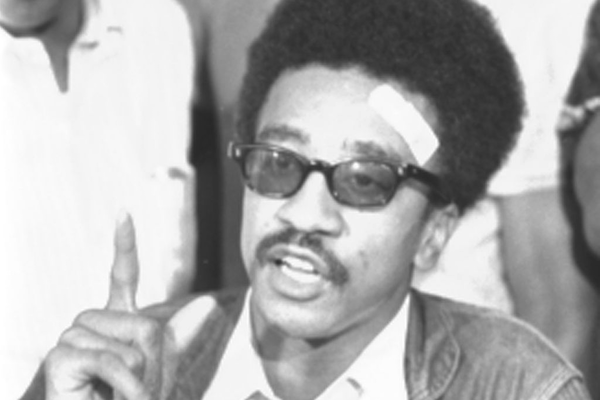

SNCC chair H. Rap Brown was excoriated after a July 1967 press conference where he told reporters: “I say violence is necessary. Violence is a part of America’s culture. It is as American as cherry pie. Americans taught the black people to be violent. We will use that violence to rid ourselves of oppression if necessary. We will be free, by any means necessary.”

Following the attack by Trump supporters on the U.S. Capitol, President-elect Joe Biden issued a statement that “the scenes of chaos at the Capitol do not reflect a true America, do not represent who we are.” While some Republicans in Congress accused the Democrats and Black Lives Matter movement of normalizing violence and rioting, other elected officials from both political parties, including Donald Trump, echoed Biden’s remarks.

Unfortunately, H. Rap Brown was right. Violence, especially racist violence directed at African Americans, is as “American as cherry pie.” Colonial America was founded on the violence of the trans-Atlantic slave trade and chattel slavery. In New York City, in 1741, enslaved Black people, suspected of planning an insurrection, were tortured to confess, as many as three dozen were publicly executed, and an estimated 70 were sent to Barbados to work and die on the island’s sugar plantations.

In the antebellum United States violence against African Americans was not just a Southern phenomenon. Before and during the American Civil War there were anti-Black and pro-slavery riots that resulted in murder in Cincinnati in 1829, 1836, 1841, in New York City in 1834 and 1863, in Connecticut in 1834 and 1835, in Boston in 1835, in Illinois in 1837, in Philadelphia in 1838 and 1842, in Kansas in 1856, and in Detroit in 1863. With a death toll of 120 people, the 1863 New York City draft riot that led to the lynching of Black men on Manhattan streets remains the largest and most deadly urban riot in United States history.

After the Civil War ended white racial violence against now freed Black people erupted in Memphis (1866), New Orleans (1866, 1874, 1895 and 1900), Tennessee again in 1868, Mississippi (1871), Louisiana (1873), Alabama (1874), South Carolina (1876 and 1898), and Atlanta, Georgia (1906). During the 1866 riots in Memphis and New Orleans as many as 100 Black men and women were murdered. In Colfax, Louisiana, a white militia murdered as many as 150 Black men in 1873. In 1898, a white mob in Wilmington, North Carolina overthrew an interracial elected government. Rioters destroyed Black-owned property and businesses and killed as many as 300 people.

As the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama documents, between the end of Reconstruction in 1877 and 1950, racial terrorism led by groups like the Ku Klux Klan, including former Confederate soldiers, swept through the South to enforce Jim Crow segregation, protect unfair labor relations, and deny African Americans the right to vote. There were over 4,000 lynchings in twelve Southern states. An estimated six million Black people eventually fled north and west to escape the South’s terrorist regime.

Again, racist violence was not confined to the South. In 1910, after Jack Johnson, the defending heavyweight champion and an African-American defeated James J. Jeffries, a white former champion, anti-Black riots broke out in Atlanta, Cincinnati, Chicago, Columbus, Houston, Lo Angeles, New Orleans, New York, Philadelphia, and St. Louis. During and after World War I, as African Americans moved north to escape racist violence in the South and to find newly opening factory jobs, they were attacked in Chester, Pennsylvania, East St. Louis, Illinois, Omaha, Nebraska, Wilmington, Delaware, New York, and Chicago. White mobs destroyed hundreds of black homes and businesses on Chicago’s South Side. Over 1,000 Black families were left homeless. The worst white mob violence was in Tulsa, Oklahoma in 1921 where white rioters, many deputized by local police, attacked and destroyed homes and businesses in the Greenwood District, a prosperous Black community. The Tulsa massacre is considered the worst incident of racial violence in United States history.

White attacks on Black people erupted again during World War II as African Americans challenged segregation in jobs and housing. Whites rioted against Black workers and families in Beaumont, Texas, Mobile, Alabama, Detroit and Los Angeles. After the war there were a number of anti-Black, anti-integration riots in the Chicago metropolitan area. The Chicago Commission on Human Relations recorded over 350 serious attacks on Black families trying to move into what had been white Chicago neighborhoods between 1945 and 1950 alone, while Chicago Police Department reportedly did not intervene to stop the violence. In Cicero, a Chicago suburb, 4,000 whites attacked an apartment building where a Black family lived in 1951.

During the Civil Rights movement Black and white activists were repeatedly assaulted and a number were murdered, including Rev. George Lee and Lamar Smith in Mississippi in 1955, Herbert Lee in Mississippi in 1961, William Lewis Moore in Georgia in 1963, Medgar Evers in Mississippi in 1963. James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner in Neshoba County, Mississippi in June 1964, Jimmie Lee Jackson, Rev. James Reeb and Viola Gregg Liuzzo in Alabama in 1965, Samuel Ephesians Hammond Jr., Delano Herman Middleton and Henry Ezekial Smith in South Carolina in 1968, and the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. on April 4, 1968 in Memphis, Tennessee. In the 1970s, efforts to racially integrate schools in Boston and Brooklyn led to attacks on school buses.

In December 1986, Michael Griffith was chased onto a highway by a white mob after his car broke down near their Howard Beach, Queens neighborhood in New York City. Griffith was struck and killed by a car. In August 1989, Yusef Hawkins was shot to death after being attacked by a white mob in Bensonhurst Brooklyn in New York City. Hawkins had gone to Bensonhurt to inquire about a used car that was for sale. In August 1997, Brooklyn police tortured Abner Louima in their precinct house.

The advent of the cellphone camera finally exposed the extent of police and vigilante violence to a broader (meaning white) public, and the Black Lives Matter movement demanded that we “Say Their Names”: Ahmaud Arbery (Georgia); Sandra Bland (Texas); Michael Brown (Missouri); Eleanor Bumpus (New York); Philando Castile (Minnesota); George Floyd (Minnesota); Eric Garner (New York); Freddie Gray (Baltimore); Trayvon Martin (Florida); David McAtee (Kentucky); Tony McDade (Florida); Laquan McDonald (Chicago); Tamir Rice (Cleveland); and Breonna Taylor (Kentucky).

A violent United States committed genocide against North America’s indigenous people. Immigrants to the country were continuously attacked by nativist groups. Police and troops were used to break strikes, suppressing the rights of workers. If the United States is going to heal the divide exacerbated by Donald Trump during his presidency, it will have to recognize that violence, especially racial violence directed against African Americans, has been a big part in the past of who we are as a nation.