A CIA Historian’s Photos of the Afghan War Tell the Story of Those Being Left Behind in Afghanistan

On May 1, the Pentagon officially began withdrawing troops from Afghanistan, thus ending an extraordinary, two decade long war fought under four presidents (a departure I have criticized from the strategic perspective). I know this land well from my journeys across more than half of its provinces as a professor of Afghan history and as an employee of the CIA’s Counter-Terrorism Center (see HNN article on my journey to the Agency here). I was tasked by the CTC with tracking the movement of Taliban and Al Qaeda suicide bombers, who I discovered were being dispatched into our team’s zone from neighboring Pakistan’s North Waziristan tribal agency as part of a terroristic effort to shatter the democratic institutions we were attempting to build there. I also worked at a Forward Operations Base in Regional Command East as a S.M.E. (Subject Matter Expert) for legendary insurgent-hunter, General Stanley McChrystal’s, U.S. Army Information Operations team.

During the course of my journeys over more than half of Afghanistan’s war-torn provinces, I came to love the ancient, almost timeless people of this land, many of whom dreamed of a building a better world with American help. While carrying out my independent scholarly fieldwork, and on my solo missions for the CIA and US Army beyond the safety of our base’s walls in what my team described as the Afghan “Red Zone,” I also did something that none of my US Army comrades---who traveled in convoys and were restricted by ROEs (Rules of Engagement)---could do. I freely photographed the fascinating Afghan people around me as they went about their lives in an active war zone.

Sadly, my rare photos are images of a world that is, in many ways, already fading as the Taliban continue their relentless march from the half of the country that they have already conquered in recent years. I fear these photos may be some of the final record of a threatened way of life---like those photographs taken of Afghanistan in the 1960s when Western tourists visited this relatively stable kingdom and found Westernized Afghan women wearing miniskirts---that will soon disappear. When our final support troops depart by September 11th, the increasingly confident Taliban are expected to launch a nationwide assault on an embattled Afghan democratic government ally that, like our former South Vietnamese allies, will be left to fend for itself without its American “big brothers.”

1. The Warlord. In this photograph, that could have almost come from the Middle Ages, my friend and focus of my book The Last Warlord. The Afghan Warrior who Led US Special Forces to Topple the Taliban Regime, the legendary Uzbek Mongol cavalry commander General Dostum, is pictured riding his prized war stallion Surkun. He rode Surkun into combat alongside horse-mounted U.S. Special Forces Green Berets to overthrow the ethnic Pashtun-dominated Taliban regime in 2001. Hundreds of his riders were killed in the desperate mountain campaign against their Taliban blood enemies that was won in just two months with only 300 US troops. These allied proxy fighters are the unsung heroes of the war on the Taliban and, under Dostum, Mongol horsemen boldly rode into war to change the course of history for the first time in hundreds of years (see my video of this remarkable campaign here).

Led by the larger-than-life secular warlord Dostum---who was brilliantly portrayed in the movie 12 Strong. The True, Declassified Story of the Horsesoldiers by Iranian actor Navid Negahban---the northern Persian-Tajik, Uzbek-Mongol and Hazara-Shiite Mongol tribes joined with a Green Beret A Team led by Captain Mark Nutsch (portrayed as a modern day Lawrence of Arabia by Thor actor Chris Hemsworth) in breaking out of their remote mountain base to topple the hated Taliban regime by December 2001. See my article on the making of 12 Strong and my efforts to bring authenticity to the remote New Mexico mountain movie set where this movie, whose Afghan half was based on my book, was filmed here.

2. The Girl. I photographed this girl in a roadside tent babysitting little brother while her parents worked in the fields. At nine years old she was charged with protecting him and the family tent by herself. While American children grow up safely in kindergartens, learning with technology in advanced schools, partaking in school sports, dating, having access to orthodontics and other medical care, books, computers, baby seats, and internet, Afghan children do not have such unimaginable luxuries. Many die as infants from disease and lack of access to medical help. I have no idea what became of this curious and welcoming girl’s fate, but in Afghanistan many impoverished children like her do not get the opportunity to learn how to read and write.

3. The Chicken Fighters. My weekly visit to the Friday afternoon chicken fights in Kabul, a favorite past-time for men who bet on winners in a hillside garden beloved by Kabuli families known as the Bagh e Babur. The famous Garden of Babur was built around the marble tomb of the 16th Turkic-Mongol Muslim warlord Babur “The Tiger.” This warlord marched out of Kabul with his cannon-equipped Central Asian warriors and fought his way across Hindustan to forge the legendary “Moghul” dynasty, famous for the Taj Mahal.

Many Afghans enjoy timeless recreational activities of the sort their ancestors did hundreds of years ago. Such past-times include two-humped Bactrian camel fighting in the Uzbek north, kite flying, and chess. Among the Afghans’ most cherished sports is the ancient horse-mounted Afghan “polo” game of buzkashi played by whip-wielding horse warrior-heroes known as chapanzades. These predominately Turkic-Mongol Uzbek and Hazara riders---who are feted as heroes in the same way Americans hero worship their baseball or football players---play a game first introduced to the Eurasian nomads by Genghis Khan the Jehanger (World Conqueror) in the 13th century to teach his warriors how to be tough.

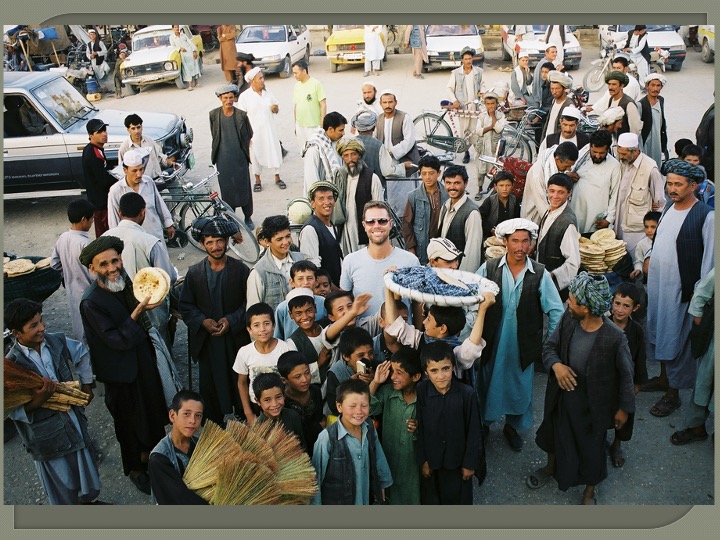

4. The Hosts. Me (in sunglasses) in the middle of a smiling crowd of curious Afghans, of the sort that often gather around a Westerner when he or she appears in their midst. I was always amazed at the warm welcome I received while traveling across this land. I was regularly invited into Afghans’ simple homes as an honored American guest. There, my impoverished, but thrilled, hosts would eagerly offer me lamb or goat, often after slaughtering their only source of meat, to honor me. The warmth I experienced in my travels compared drastically to the stereotypical images many Americans have of this as a uniformly hostile land. I wish many of my fellow Army teammates who were confined to our base could have had this sort of experience to get to know the Afghans.

Hospitality to honored guests like myself is an ancient tradition all of Afghanistan’s ethnic groups cherish. For them offering panagah (sanctuary in Persian) or melmastiia (hospitality to guest in need in Pashto) is almost a religious duty. So protective of me was the Uzbek leader General Dostum in my visits to his northern realm, that he had armed fighters sleep outside my door and follow me around (much to my annoyance) to keep me safe. But the most famous recipient of melmastiia was the Saudi Arabian terrorist Osama bin Laden who was granted sanctuary by the Taliban of the south in 1996.

5. The Burger and Pizza Chef. In the bustling capital of Kabul, I found Western-inspired sights that would have been unimaginable under the grim Taliban masters. For example, I found previously-banned beauty shops, internet cafes that brought the world to previously isolated Afghans, a few (now closed due to Taliban attacks) bars for foreign aid workers and military contractors, a shopping mall (whose entrance was protected by armed guards with metal detectors to protect it from suicide bombers), TV studios, and even American-style restaurants, including one of my favorites KFC, Kabul Fried Chicken.

The restaurant pictured above was run by an Afghan who had, like tens of thousands of his people worked on a U.S. base. There he learned how to make such popular dishes as pizza and hamburgers. Two decades of American cultural influence and exposure to the modern West has radically transformed many Afghans, especially those who are better off and live in the cities. This influence, in the form of women on such Afghan channels as Tolo, young men wearing American-style clothes, women in university, and young people on Facebook, will be hard for the provincial Taliban to completely eradicate should they re-conquer Kabul and other comparatively cosmopolitan, liberal cities.

6. The School Girls. A group of middle school girls who were, after five years of being denied the right to be educated by the Taliban, excited to be attending school. The girl in the middle was crying as she told the story of how her parents were killed by the Taliban. She worriedly told me “the day the Americans leave the Taliban will return and execute us if we try to learn to read and write which is forbidden by their law.” Girls like her told me horror stories of the Taliban misogynists’ draconian brutality against women. One teenager told me of a girl in her village who was stopped by the Taliban’s dreaded, whip-wielding moral police, the Committee for the Prevention of Vice and Promotion of Virtue, and discovered upon investigation to have had forbidden finger nail polish on her fingers. She was then dragged screaming to the town square. There, she had her fingers cut off in public with a sword as a Taliban mullah or priest read passages from the holy Koran condemning her as a “prostitute.”

In a sign of things to come, and stark warning to girls who might have hopes for continuing to get the sort of education they have been able to receive for 20 years, on May 8th terrorists slaughtered 30 people, mainly school girls, and wounded another 52 with a massive bomb outside a girl’s school.

7. The Guardians of the Buddhas. High in the remote fastness of the mighty Hindu Kush Mountains live the Shiite Mongol Hazaras who have been terribly repressed by the Sunni Muslim extremist Taliban from the southern lowlands. The Hazara highlanders’ villages were burned in the late 1990s and their people continue to be slaughtered even in their weddings by the Sunni Taliban and ISIS fanatics who considered them to be Shiite “heretics.” Under the influence of their notorious Al Qaeda Saudi guest Osama bin Laden, the Taliban iconoclasts also blew up the magnificent stone Buddhas carved into the wall of one of Afghanistan’s most scenic valleys, the 8,000 foot high Vale of Bamiyan, by the ancient Aryan Tokharians in the 6th century.

Approximately 800 years after they were carved by the Buddhists inhabitants of the valley, Mongol garrisons settled in the heights of the Hindu Kush (the name Hazara signifies a Unit of One Thousand Troops) and gradually came to see themselves as protectors of Afghanistan’s most prized archeological treasure. The Taliban’s senseless culturecide destruction of the locally cherished Buddhas that appeared on the Afghan currency was a calculated blow to the Hazaras’ pride and spirit.

Here I am photographed standing with Hazara kids with beautiful Vale of Bamiyan behind me and the empty dark niche carved into its rock wall where the 180 foot, larger of the two Buddha carvings guarded the secluded valley for a millennia and half. I was led by a local guide through Taliban landmines to the mournful, rubbleized ruins of the massive Buddhas. He told me that his people believe that when evil is approaching their lands, the ghosts of people in nearby ruins who were slain by Genghis Khan scream in warning. My Hazara friends on Facebook tell me their elders claim them the voices are now screaming again as the Taliban once again approach their mountains from the south.

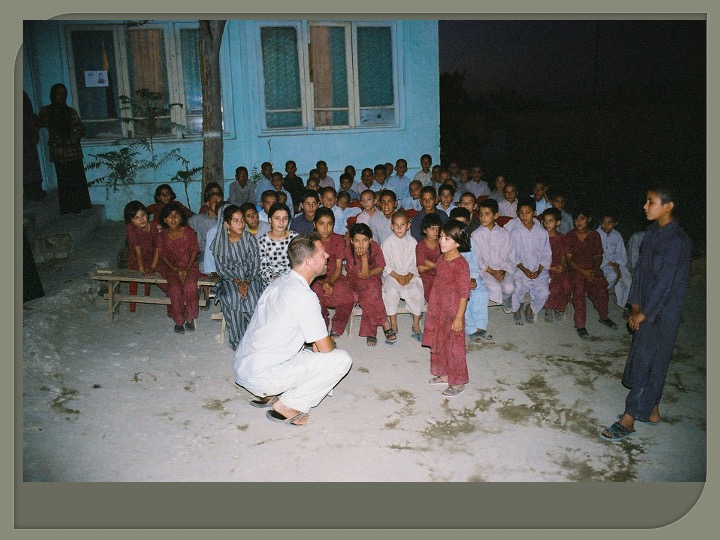

8. The Orphans. During my visit to this home for war orphans run by a wonderfully compassionate Afghan woman, I encountered this angel who sang an Afghan song for me. I wanted to take her, and all of them, home with me when I found they were sleeping three to a bunk bed and living on a simple, twice-daily meal of porridge and bread. When I asked about their future, the kind woman who ran the shelter told me the girls might get lucky and be married off as a second, third, or fourth wife to an older man and the boys might get lucky and be adopted to serve as laborers. As grim as these fates seemed, they were far better than the fate of hundreds of thousands of Pashtun war orphans in the 1980s and 1990s who were adopted by fundamentalist madrassas (religious seminaries) where they were indoctrinated by Saudi-funded mullahs to become fanatical, misogynistic Taliban.

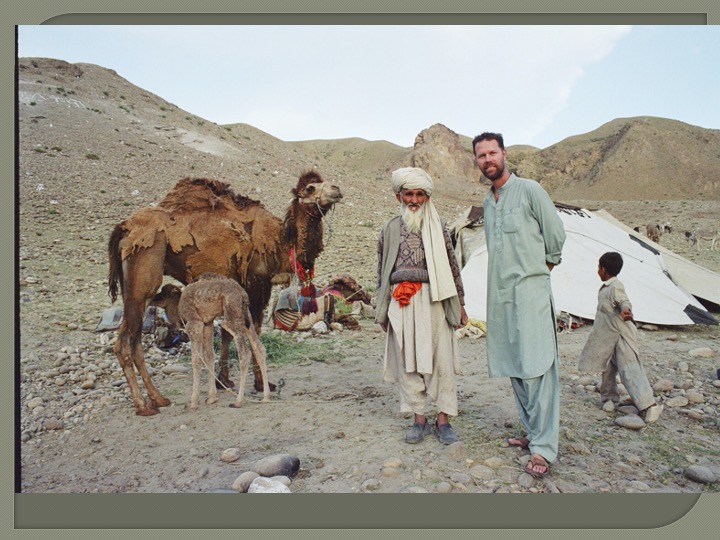

9. The Nomads. As you drive around Afghanistan’s south, you encounter wandering Pashtun sheep and goat herders who have nomadized on these lands since the dawn of time. These primordial nomads known as Kuchis live disconnected from settled villagers, except when they wander into their markets to sell sheep skins, beautiful hand-woven carpets, milk, or meat. The Pashtun Taliban rarely interfere with the migrating Kuchi tribes who live by their own ancient rules. For this reason, they were, and hopefully will be, less impacted by the Taliban’s harsh enforcement of shariah Islamic law and their relatively free women rarely wear the all-encompassing burqa veil. The elder on my right welcomed me to his encampment with the famous hospitality of his people and I was given insights into a timeless world of a people who do not have cell phones (of the sort many Afghans now have) or even electricity, running water, or heating.

10. The Americans. I chose not to share a typical combat mission photo, but to instead include this image, of the sort few non-military people see, of my base members enjoying rare down-time from the strains of war to celebrate July 4th. Here two of our base members who were famous for their “Scottish-rock” songs (hence the kilt and bag pipes) entertain the base during an Independence Day barbecue. While life as a “Fobbit” on a F.O.B. (Forward Operations Base) could be stressful—we had a car-borne suicide bomber detonate at our heavily guarded gate killing several soldiers, some mortar shelling, and a PTSD suicide that summer—we were far better off behind our walls and blast barriers than troops living in much smaller, remote, exposed C.O.P.s (Command Outposts).

Almost 800,000 American troops served in Afghanistan and they drastically transformed this land that time forgot on many levels. I remember making the long drive from the town of Jalalabad near the Pakistani border, over the mighty Hindu Kush Mountains, and across the burning deserts of the north to the Uzbekistan border on a beautiful ribbon of black tarmac and being proud we had built it (this road was far smoother than those found in my hometown of Boston!). American troops also built schools, hospitals, and wells, de-mined fields, trained a police force of 116,000 and army of 180,000 troops, and helped prevent the Taliban insurgents from taking a single regional capital or town of any size for twenty years.

History shows that more aid was pumped into the building of Afghanistan’s democracy than was spent to rebuild post-World War II Europe in the Marshall Plan (when factoring in inflation). These efforts brought much, but certainly not all of this un-developed land (that was never colonized or modernized the way say Russian-Soviet Uzbekistan was), from the Middle Ages into the 21st century. They also gave Afghanistan a “government in a box” that included mandatory seats for women, ended the Taliban repression of the northern Uzbek Mongol, Tajik Persian and Hazara Shiite Mongol ethnic groups, gave girls a chance to be educated, and gave all those who dreamed of an escape from the medieval cruelty of the Taliban a breathing space to try to forge a pluralistic democracy where women’s and minorities’ rights were respected. It remains to be seen how permanent these fragile gains are.

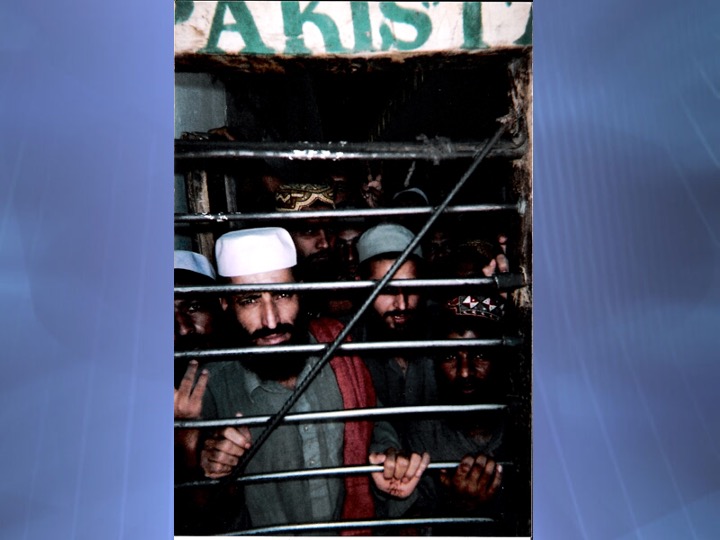

11. The Taliban. I took this photograph in a fortress-like prison in the northern deserts where thousands of Taliban prisoners of war were being held by General Dostum. I was given the rare chance to sit down with the notorious Taliban and talk with them while my glowering Uzbek guards looked on. The captives ranged from hardcore fanatics, including one who said he would kill me as an infidel if he was not handcuffed, to less extreme “village Taliban” who had been paid to fight. I also met Pakistani Taliban who had been lured into Afghanistan in 2001 to defend it from the American “infidels.” As I took in the despair in the prisoners’ eyes, like the one I captured here, part of me felt sorry for them.

But when I remembered the stories of school girls who had had disfiguring battery acid thrown in their face by Taliban to punish them for daring to get an education and the shredded bodies of victims of one of their senseless suicide bombings I encountered, I forgot such emotions. Should they conquer post-American Afghanistan, girls will once again be forbidden from sitting in a classroom with boys to learn to read and write, Western-style restaurants and beauty salons will be banned (along with buzkashi and chicken fighting), and the repressed Shiite Hazaras of the Hindu Kush Mountains will once again be repressed. I am still haunted by one Taliban prisoner’s bold boast of the Taliban’s famously defiant mantra to me back in 2003 “You Americans may have the watches, but we have the time…We will outlast you.”

Sadly for the Afghan people, it appears he was right.

For more of Dr. Williams’ photos from Afghanistan and Islamic Eurasia, articles, videos and his books see his website at: brianglynwilliams.com

I would like to thank Carol Hansen and my wife Miriam Braz Williams for their assistance with this article