The Issue of Visibility in Latino Art

Chicano mural in El Paso, Texas. Note the tears flowing into the Rio Grande River. Image included in the “Painted Walls of the Barrio” exhibit. Photo: Ricardo Romo, 1983.

For border artists, many of whom incorporate imagery related to immigration, there has never been a more urgent time for artistic expression than now. El Paso has been one of the busiest immigration centers on the 2,000-mile international border as thousands of refugees arrive daily at this West Texas border station. Many border artists see the turmoil and complexities of immigration policy close up. El Paso’s active muralist community was featured in an excellent article by Diana Spechler, “Art Without Borders,” in the New York Times on April 11.

Spechler made a strong case for communities like El Paso to support the work of its muralists, writing that ”we need a mode of connection beyond ‘reaching across the aisle’... We need art that shakes us and we need lots of it--not just in major cities, but also in rural America, in suburbs.” Spechler’s conclusions are especially worth considering as she makes a call for “art as commentary--not the safe, sterile kind--art to counteract deception, art that reminds us that even when things seem beyond fixing, they are not beyond describing.”

I commend Spechler’s call for more public art --art that makes one think, art that offers critical commentary through its imagery. Nearly forty years ago I led a documentary team to El Paso, Houston, San Antonio, and other Texas communities that had established a mural tradition to capture the prominent Latino murals. Our mission resulted in an art presentation at the Institute of Texan Cultures in San Antonio titled: “Painted Walls of the Barrio.” The visual presentation had a twenty-year run at the Institute where thousands of school children were treated to a 30-minute show in the Institute’s expansive rotunda showing images simultaneously on four large walls. The murals had many historical and social themes that always elicited questions from the visiting school children.

Chicano mural in Houston Texas. Artist: Leo Tanguma. Mural image detail included in the “Painted Walls of the Barrio” exhibit. Photo: Ricardo Romo, 1983.

Public art has many champions, and I have been one for many years. But in this essay, I offer another art option: Recognizing that our tax-supported museums have only marginally collected Latino art, I propose that major museums in Texas, which include those in Houston, Dallas, Fort Worth, San Antonio, and El Paso reassess their collection’s holdings by Black, Latino, and Asian artists. This can be done with the assistance of their in-house curatorial staff, but may also require the appointment of special community artists and art scholars to discuss and assess the diversity of the museum collections and make recommendations on how to remedy any shortcomings.

President Joe Biden’s support for the arts is generous in the stimulus package which according to GrantNews, allocated $15 billion for arts grants. Most artists rely on exhibitions or art shows to display and sell their art. With the pandemic, nearly all museums and art galleries across the nation shuttered their doors. Artists were left to employ virtual shows to exhibit their works. Artists I spoke with did not see much advantage in virtual shows. Overall, sales were dramatically down, and most artists had to rely on other types of work to survive financially. While the stimulus funding will help nonprofits with trained staff and those who know how to apply for grants, artists worry that the self-employed artists who have depended on art galleries and art show sales will see less help initially.

Houston Texas mural. Restoration of Leo Tanguma’s mural completed by Gonzo. Photo: Ricardo Romo, 2019.

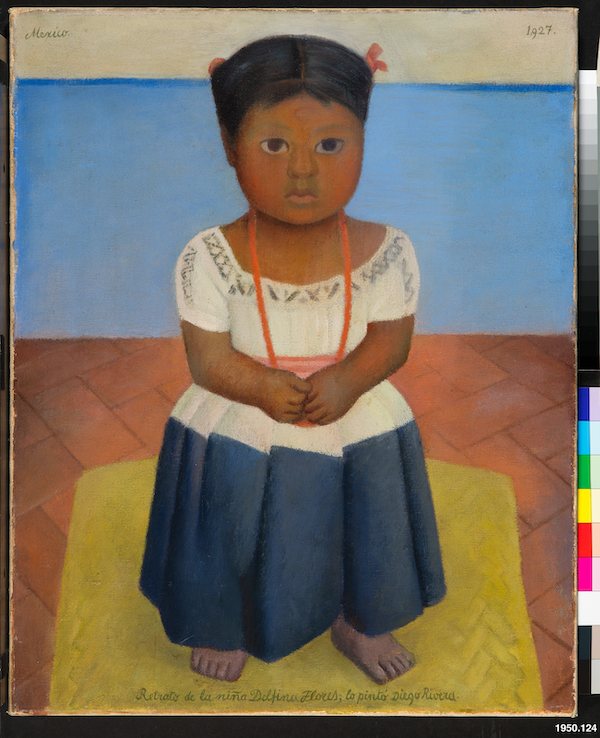

The definition of Latino art is broad and can include art from Mexico, Central America, and Latin America as well as U.S.-born Latinos. Some museums collected the works of Latino artists early on. Marion K. McNay, who later established her beautiful home as an art museum in San Antonio, for example, collected a stunning painting of a young girl by Diego Rivera in the early 1920s. Several university museums, the University of California-Santa Barbara Museum of Art and the University of Texas-Austin art museums acquired the works of David Alfaro Siqueiros. The Boston Museum purchased a painting by Spanish-Mexican artist Jose Arpa in 1899. The sale of that painting, which was in a San Antonio exhibition that same year, convinced Arpa to move from Mexico City to San Antonio the following year.

Before World War II, there were relatively few American-born Latino artists known to the general public and museums. San Antonio resident and landscape artist Porfirio Salinas became the exception in the late 1940s when the newly elected Texas Senator Lyndon B. Johnson acquired several of his bluebonnet paintings and hung them at his Junction, Texas ranch and in his U.S. Senate office. Later when Johnson won the presidency in 1964, his fondness for Salinas’ wildflowers and landscapes was such that nearly all the paintings in the Oval Office were by Salinas.

Porfirio Salinas. “The Alamo.” Oil on canvas. Courtesy of Fort Sam Houston Museum, San Antonio,Tx. Photo by Ricardo Romo

The Witte Museum in San Antonio, founded in 1926, was one of the first museums in America to exhibit and acquire works by Mexicans and American Latinos. Mexican art first came to Texas in September of 1927 when the San Antonio Art League brought 200 paintings from Mexico City for an exhibit at the Witte Museum. Witte curator Amy Fulkerson’s research on Witte exhibits found references in the local papers of “200 original paintings” lost in train transport to San Antonio. The paintings were found safe, although we know little about the incident. That same year, Marion K. McNay loaned her “Delfina Flores” painting of a young Mexican child by Diego Rivera to the Art League.

Diego Rivera, Delfina Flores, 1927. Oil on canvas, 32 ¼ x 26 in. Collection of the McNay Art Museum, Bequest of Marion Koogler McNay © Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, México, D.F./ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

It has been 90 years since Texans first demonstrated an interest in Mexican art. In recent decades that interest has grown. As the larger cities of the state become increasingly Latino, more will be expected from publicly supported museums. The moment is ripe for bringing Latino art to public spaces and public museums. The number of talented Latino artists has multiplied over the past two decades, and the opportunity to make their work visible is now.