Recent Discovery Shows Women Scholars have been Hiding in Plain Sight of History

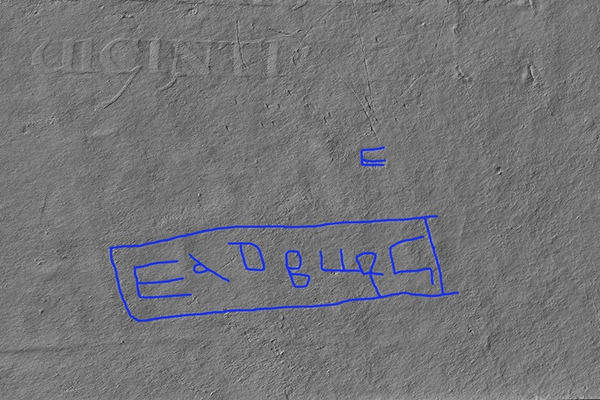

Digital imaging revealed Eadburg's inscription on the pages of a manuscript of the Acts of the Apostles in Oxford's Bodleian Library.

The poignant discovery of an 8th-century Englishwoman scratching her name no less than 15 times upon a Latin manuscript reminds us that women have been leaving their mark upon literature since time immemorial.

The manuscript was unearthed last year by researchers at the Bodleian Library in Oxford and is a Latin copy of the Acts of the Apostles, written in England some time between AD 700 and AD 750. So, 1,300 years ago someone – we can only assume Eadburg herself – repeatedly inscribed her name in the margins of the text, surely a sign that she herself either created, used, or owned the manuscript.

Eadburg's name is now visible to us through the use of advanced "photometric stereo" technology that employs multi-dimensional scanning to bring to light drypoint inscriptions (ie her scratchings). This remarkable technology means Eadburg can finally be seen, over 1000 years later.

While scholars have typically dated the emergence of women writers in England to the later Middle Ages (around the 15th century), Eadburg’s writing of her name reminds us that women were engaging with texts much, much earlier than this.

Most scholars have lamented that it is scanty evidence that has rendered most of these female writers invisible. And we are—correctly—advised not to assume anything from a lack of evidence. As a recent Guardian editorial on the Eadburg discovery reminds us: “absence of evidence cannot necessarily be equated with absence of achievement.”

But I believe this is not a correct interpretation of Eadburg’s story. The difficulties with rendering women writers visible are manifold. But the primary obstacle is not a lack of evidence. Instead, it’s a lack of sufficiently creative approaches. The Bodleian discovery shows us that Eadburg was always there, hiding in plain sight. In other words, the evidence was not missing. It just took the right technology to be able to see her.

My own research into women writers in Africa in the twentieth century has striking parallels with Eadburg’s story. Scholars typically argue that significant women writers only became active in the later decades of the century, from the 1960s onwards. The commonly cited issue, once again, is “evidence” – what remaining manuscripts exist by women writers of the early twentieth century? Almost none at all.

Yet as with Eadburg and medieval literary women, what we need is not necessarily more evidence, but rather different approaches to the evidence we do have, coupled with a willingness to consider less conventional types of evidence.

Scientists have developed exciting photometric stereo technology – the ability to see a manuscript in 3D. Historians need to be similarly resourceful in our efforts to "see" literary women of the past. Denied opportunities to publish and formally affix their names to documents, many women's names have to be searched for in unusual and unconventional locations. Historians need to create our own equivalents of 3D imaging.

My own biography of Regina Twala, an unknown twentieth-century female writer is a case in point. Twala never managed to publish a single book during her lifetime. This was not for lack of producing content (she authored as many as five different manuscripts) nor for trying (she repeatedly approached local and international publishers, with no success).

So there is certainly no “evidence” in terms of published books with which to reconstruct Twala’s career as a writer.

But to only consider published work as the defining quality of a female writer is unnecessarily limiting. Publishing was a highly restrictive industry for twentieth-century women in South Africa – even more so for Black women negotiating the strictures of a sexist and racist society. To search for evidence in places where we already know we likely won’t find it is not an effective approach.

While Twala “failed” to publish, she wrote hundreds of articles and columns for newspapers across South Africa. She also wrote hundreds of letters throughout her lifetime, largely to her second husband, Dan Twala.

While neither journalism nor letters are usually considered “serious” literary output, my book argues that this is precisely the kind of evidence we ought to be considering in our efforts to chart the history of women writers in Africa.

While publishing presses were often closed to women, women were able to use the relatively more egalitarian forum of the newspaper to regularly air views, express opinions, and experiment with genre and style as well as content. And many women wrote using pseudonyms, shielding themselves from the censure of hostile men. Letters, moreover, were truly open to anyone, a humble platform that could nonetheless generate exciting literary experimentation.

And despite our stereotypes of letters as “private,” Twala’s letters were not only read by her husband, but circulated more widely in her community, passed around in a whole network of friends, family, and sometimes even to those whom she did not even know.

In these ways, early twentieth-century newspapers and letters in Africa reveal the full extent of the innovative literary work being undertaken by women, decades before the first books by female authors were published.

Finally, like Eadburg, Twala’s writing has been hiding in plain sight. But it has been rendered invisible due to being appropriated and passed off as his own by a renowned Swedish historian, Bengt Sundkler. In the 1950s, Sundkler hired Twala as his research assistant, paying her to undertake a study of religion in Eswatini. Twala diligently sent Sundkler pages and pages of research materials.

Two decades later, in 1976, Sundkler would publish Twala’s work – but under his name, not hers. Sundkler became famous for his pioneering work, Zulu Zion and Some Swazi Zionists. It was only when I compared the research notes Twala had sent Sundkler (kept in his archives in Uppsala Library in Sweden) with Sunkdler’s published book that I realized Sundkler had extensively plagiarized Twala’s material, frequently word-for-word.

Again, the issue here is not lack of evidence. Twala’s written words existed. But they were published under a European male scholar’s name, a product of a society and an academic infrastructure that operated according to racist and gendered hierarchies and rendered intellectual exploitation all too easy to accomplish.

To reiterate again, what was needed was a new approach to the existing evidence. In this case, I needed to sift through the archives of Sundkler’s research materials, read his notes against the grain in order to render visible the usually ignored processes by which scholars’ research is actually done and the nuts and bolts of how they put their arguments together. It is laborious to do this work, for sure.

But it is an approach that I am certain would yield similar discoveries for a whole host of “classic” scholarship of the twentieth century. These kinds of guerilla archival tactics would surely show that many largely male authors relied upon an army of unacknowledged female and Black intellectual labor for their published work.

Eadburg and Twala. Two women separated by over a millennium, by geography, and by race. But both alike in being literary pioneers for their times. And both demanding that we as researchers step up to the task of seeing what they left in plain sight. Their work is there for all to see - if only we find the right tools to open our eyes with.