The Two-State Solution in Israel/Palestine is as Dead as Burhanuddin Rabbani

All eyes were focused on the game of brinkmanship over the Palestinians’ bid for full United Nations membership when Afghanistan’s ethnic Tajik leader and ex-president Burhanuddin Rabbani was assassinated in Kabul on Monday (September 20). Rabbani’s murder has as much to do with the past rivalries, as well as the future, of Afghanistan and is significant, as is the battle for Palestinian statehood. The stakes are high in each case. What will transpire seems uncertain at this stage.

All eyes were focused on the game of brinkmanship over the Palestinians’ bid for full United Nations membership when Afghanistan’s ethnic Tajik leader and ex-president Burhanuddin Rabbani was assassinated in Kabul on Monday (September 20). Rabbani’s murder has as much to do with the past rivalries, as well as the future, of Afghanistan and is significant, as is the battle for Palestinian statehood. The stakes are high in each case. What will transpire seems uncertain at this stage.

I am not convinced that the Palestinian bid is necessarily doomed in the face of the United States veto (whenever the Security Council decides to vote) and Israel’s brute military force against the Palestinian population in the occupied territories. The Palestinian move does not alter the reality on the ground for now, but has the potential to transform international diplomacy, isolating the Obama and Netanyahu administrations. A vote in the United Nations General Assembly could then upgrade Palestine to be a “UN non-member state,” putting it alongside the Vatican, Kosovo and Taiwan. It would be short of full statehood, but a significant push.

Freedom from occupation comes after a long struggle and great sacrifices. It has been the case in the past and it is certainly the case with the Palestinians. I am old enough to remember apartheid in South Africa and how that system created a messy network of affluent white communities living off the labor of blacks of Bantustans, existing at the mercy of the Afrikaner regime. The power of anti-apartheid campaigners inside South Africa was no match compared to the power of the rulers.

The virtue of their cause gave them inner strength. Their plight transformed the world opinion slowly but decidedly. Today, the U.S. administration brandishes its veto because Israel’s military power is not enough. What is blindingly obvious to much of the rest of the world is the cruelty and injustice of the system of expanding illegal Jewish settlements and shrinking Palestinian towns and villages, separated by the wall. It stands as a monument of colonization and wrong. Attempts to create a social order of this nature often fail, and at a great cost.

For now, though, in the midst of an economic crisis, the issue of Palestine is the last thing President Obama wants to deal with, for it threatens his reelection in 2012. Obama’s remarks before an audience representing 193 member-states in the General Assembly, overwhelmingly supportive of the Palestinian bid, marked a dark, shameful day for the United Nations and the United States.

Uri Avnery, founder of the Israeli peace movement Gush Shalom and ex-Knesset member, reacted by saying, “Almost every statement in the passage concerning the Israeli-Palestinian issue was a lie.” Avnery described Obama at his best, and at his worst. The anger on the Palestinian side was profound.

While the demand for a “two-state solution” is under the spotlight, there is another side to the debate that is even more nightmarish for Israel’s hardline citizens and their friends. It is the idea of a single democratic state with Jews, Palestinians and Christians, all living as equal citizens of the same state. It may look farfetched now. However, as illegal Jewish settlements continue to squeeze the Palestinian land in the West Bank and Gaza, and an independent Palestinian state becomes less and less viable, the idea of a single Israel-Palestine gains credence.

The Palestinian leadership of Fatah and Hamas must be aware of the prospect. For the more diehard, committed to the idea of an Islamic (or Jewish) state, it may be beyond contemplation. But for liberal Jews and Palestinians, and others outside, it is not such a fantastic idea.

Imagine the unthinkable: Four million Palestinians of the West Bank and Gaza, with nearly eight million citizens of present-day Israel, six million of them Jews, all enjoying equal rights under the same constitution. The Israeli-Palestinian conflict has a long, destructive history behind it and similarly a difficult road ahead. However, it is beginning to point to a destination, still distant, not quite certain, and unpalatable for the Israeli ruling elite and those in friendly capitals.

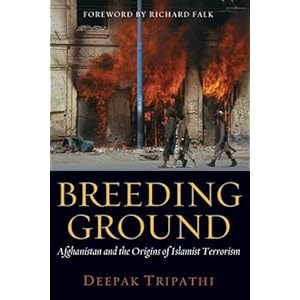

The assassination of Burhanuddin Rabbani in Kabul temporarily overshadowed the Palestinian debate in New York. Much has been made in the western press about the setback the assassination has delivered, because Rabbani was the chairman of the Afghan Peace Council, an appointment by President Hamid Karzai. In truth, the reasons behind Rabbani’s murder have much more to do with the Cold War and Afghanistan’s ethnic and political rivalries that go fifty years back—rivalries that I discuss in my book, Breeding Ground: Afghanistan and the Origins of Islamist Terrorism (Potomac, 2011).

Rabbani, an ethnic Tajik from the north, was a founder of the Islamist party Jamiat-e-Islami and a theology lecturer at Kabul University in the 1960s. His bitter rival was Gulbuddin Hikmatyar, a Pashtun student in the faculty of engineering, and a leading figure in the Pashtun fundamentalist group Hizb-i-Islami, which later split. Both were violently opposed to Afghanistan’s secular ruling elite.

Their hatred for each other was to continue through the 1980s, when both fought the Soviet occupation forces with the CIA’s help. Their rivalry grew more intense as Hikmatyar became Pakistan’s favorite, receiving the largest amount of Western weaponry and money from Saudi Arabia, channeled through the ISI of Pakistan.

When the Soviet Union withdrew in 1989 and the last Afghan communist leader Najibullah was ousted three years later, open warfare broke out between Hikmatyar’s and Rabbani’s forces. Rabbani was president of Afghanistan during the years of factional war between 1992 and 1996. Then the Taliban, successors of the Mujahideen, pushed Rabbani’s forces out of the capital, Kabul. Thereafter, he was president only in name until the Taliban were ousted following the September 11, 2001 attacks on America.

Today, Gulbuddin Hikmatyar is close to the Taliban, fighting the U.S.-led foreign troops in Afghanistan. Rabbani was living in a heavily guarded mansion in Kabul, supposedly assisting President Karzai in achieving reconciliation with the Taliban. However, the process under Rabbani’s chairmanship was a nonstarter from the beginning. It ended in his assassination by a suicide bomber who had supposedly gone to visit him for talks.

Two days before the September 11, 2001 attacks, Rabbani’s military chief Ahmad Shah Massoud was murdered by al Qaeda suicide bombers posing as journalists. The writing had been on the wall ever since for Burhanuddin Rabbani. The prospects of a controversial Tajik figure like Rabbani succeeding in negotiations with the Taliban were always remote. His assassination is like oil in the fires long raging between Afghanistan’s biggest two ethnic groups.