Friendless in the Middle East

The Arab upheavals of 2011 have inspired wildly inconsistent Western responses. How, for example, can one justify abiding the suppression of dissidents in Bahrain while celebrating dissidents in Egypt? Or protect Libyan rebels from government attacks but not their Syrian counterparts? Oppose Islamists taking over in Yemen but not in Tunisia?

Such ad hockery reflects something deeper than incompetence: the difficulty of devising a constructive policy toward a region where, other than in a few outliers (Cyprus, Israel, and Iran), populations are predominantly hostile to the West. Friends are few, powerless, and with dim prospects of taking control. Democracy therefore translates into hostile relations with unfriendly governments.

Both the first wave of elections in 2005 and the second wave, just begun in Tunisia, confirm that, given a free choice, a plurality of Middle Easterners vote for Islamists. Dynamic, culturally authentic and ostensibly democratic, these forward a body of uniquely vibrant political ideas and constitute the only Muslim political movement of consequence.

But Islamism is the third totalitarian ideology (following fascism and communism). It preposterously proposes a medieval code to deal with the challenges of modern life. Retrograde and aggressive, it denigrates non-Muslims, oppresses women, and justifies force to spread Muslim rule. Middle Eastern democracy threatens not just the West's security but also its civilization.

That explains why Western leaders (with the brief exception of George W. Bush) shy away from promoting democracy in the Muslim Middle East.

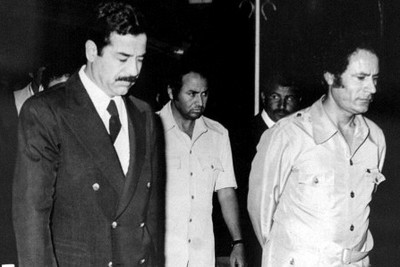

In contrast, the region's unelected presidents, kings, and emirs pose a lesser threat to the West. With Mu'ammar al-Qaddafi long ago chastened by American power and Saddam Hussein removed by American-led forces, the egomaniacs were gone by 2003 and surviving strongmen largely accepted the status quo. They asked for little more than to be allowed quietly to repress their populations and noisily to enjoy their privileges.

Saddam Hussein (left) and Mu'ammar al-Qaddafi in their salad days (circa 1985).

A year ago, Western policymakers could survey the region and note with satisfaction that they enjoyed reasonable working relations with all the governments of Arabic-speaking countries, excepting Syria. The picture was not pretty but functional: Cold War dangers had been thwarted, Islamist ones mostly held off.

Greedy and cruel tyrants, however, present two problems to the West. By focusing on personal priorities to the detriment of national interests, they lay the groundwork for further problems, from terrorism to separatism to revolution; and by repressing their subjects, they offend the sensibilities of Westerners. How can those who promote freedom, individualism, and the rule of law condone oppression?

In the Middle East, full tyranny has dominated since about 1970, when rulers learned how to insulate themselves against the prior generation's coups d'état. Hafez al-Assad, Ali Abdullah Saleh, Husni Mubarak, and the Algerian regime demonstrated with rare flamboyance the nature of full-blown stasis.

Then, last December, a butterfly flapped its wings in the small Tunisian town of Sidi Bouzid (population: 40,000), when a policewoman slapped a fruit vendor. The response toppled three tyrants in eleven months, with two more in serious jeopardy.

Tunisia's president called out the police in Sidi Bouzid in December 2010, but to no avail.

Summing up the West's policy dilemma vis-à-vis the Middle East:

- Democracy pleases us but brings hostile elements to power.

- Tyranny betrays our principles but leaves pliable rulers in power.

As interest conflicts with principle, consistency goes out the window. Policy wavers between Scylla and Charybdis. Western chanceries focus on sui generis concerns: security interests (the U.S. Fifth Fleet stationed in Bahrain), commercial interests (oil in Saudi Arabia), geography (Libya is ideal for Europe-based air sorties), the neighbors (the Turkish role in Syria), or staving off disaster (a prospect in Yemen). Little wonder policy is a mess.

Policy guidelines are needed; here follows my suggested triad:

Aim to improve the behavior of tyrants whose lack of ideology or ambition makes them pliable. They will take the easiest road, so join together to pressure them to open up.

Always oppose Islamists, whether Al-Qaeda types as in Yemen or the suave and "moderate" ones in Tunisia. They represent the enemy. When tempted otherwise, ask yourself whether cooperation with "moderate" Nazis in the 1930s would have been a good idea.

Help the liberal, secular, and modern elements, those who in the first place stirred up the upheavals of 2011. Assist them eventually to come to power, so that they can salvage the politically sick Middle East from its predicament and move it in a democratic and free direction.