Kastelorizo—Mediterranean Flashpoint?

Remember the name Kastelorizo; you heard it here first.

It is the far-flung, easternmost island of Greece, 80 miles from Rhodes, 170 miles west of Cyprus, but just 1 mile off the coast of Turkey. Kastelorizo (in Greek, Καστελόριζο; or officially Megisti, Μεγίστη) is tiny, comprising just 5 square miles, plus some yet smaller, uninhabited islands. Its 430 inhabitants are way down from 10,000 in the late nineteenth century. The Lonely Planet travel guide has picked it as one of the four best Greek islands (out of thousands) for diving and snorkeling. There's no public transportation from nearby Anatolia, only from distant Rhodes by airplane or ferry.

Kastelorizo off the Anatolian coast and between Rhodes and Cyprus. (For an enlarged version of this map, click here.)

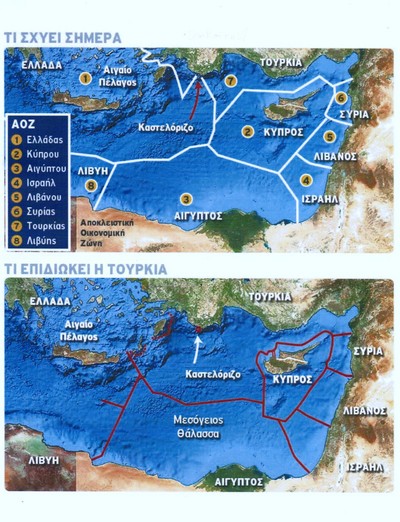

That Athens controls this wisp of land implies it could (but does not yet) claim an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) in the Mediterranean Sea that reduces the Turkish EEZ to a fraction of what it would be were the island under Ankara's control, as maps reproduced from the Cypriot newspaper I Simerini illustrate show. The top map shows the Greece claiming its full 200-nautical mile EEZ and controlling Kastelorizo EEZ (indicated by the red arrow); the bottom one shows the Greek EEZ minus Kastelorizo (indicated by the white arrow).

Were Athens to claim its full EEZ, Kastelorizo's presence would make its EEZ contiguous with the EEZ of Cyprus, a factor with great import now, at a moment of massive off-shore gas and oil discoveries. Kastelorizo with an EEZ benefits the emerging Greece-Cyprus-Israel alliance by making it possible to transport either Cypriot and Israeli natural gas (via pipeline) or electricity (via cable) to Western Europe without Turkish permission. This has taken on special urgency since Nov. 4, when Turkey's minister for energy, Taner Yıldız, announced that his government would not permit Israeli natural gas to transit Turkish territory; Ankara will likely also ban Cypriot exports.

Turkey's Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his ruling AKP party colleagues accept Greek control of Kastelorizo and its six nautical miles of territorial waters, but not more and certainly not its full EEZ rights. Indeed, in their eyes, Greek assertion of an EEZ constitutes a casus belli. By neutering Kastelorizo, Ankara can lay claim to large economic area in the Mediterranean and block cooperation among its adversaries. This is why the island could become a flashpoint.

Top: Greece's EEZ with Kastelorizo. Bottom: Greece's EEZ without Kastelorizo. (For an enlarged version of this map, click here.)

Several developments point to AKP intimidation of Greece concerning Kastelorizo. First, in September, it authorized a Norwegian ship, the Bergen Surveyor, accompanied by other sea craft, to begin prospecting for gas and oil south of Kastelorizo, including some of the island's continental shelf. Second, Turkish warships have trained with live ammunition between Rhodes and Kastelorizo. Finally, Turkish military aircraft four times in 2011 overflew Kastelorizo without permission, sometimes very low with reconnaissance aircraft.

This bellicosity fits a larger pattern. The AKP government, especially since it has took full control of the armed forces in late July, has shown increasing hostility toward Cyprus, Israel, Syria, and Iraq. In addition, Ankara has long denied Cyprus its EEZ, so doing the same vis-à-vis Kastelorizo builds on an established policy. Indeed, the Turks' brutal, napalm-assisted 1974 conquest of the northern 36 percent of Cyprus set a precedent for seizing nearby island territory. Grabbing Kastelorizo would require about as much time as reading this article.

George Papandreou, then prime minister of Greece, visited Kastelorizo in April 2010.

So far, responses to heightened Turkish aggressiveness in the Mediterranean have focused on deterring Turkish feints toward gas and oil reserves in the Cypriot EEZ, with navies and statements from the United States and Russia backing the Republic of Cyprus' right to exploit its economic resources. Cypriot president Demetris Christofias warned that if Ankara persists with its gunboat diplomacy, "there will be consequences which, for sure, will not be good." Israeli Deputy Foreign Minister Danny Ayalon told the Greeks that "If anyone tries to challenge these drillings, we will meet those challenges" and his government enhanced security not only for its own maritime fields but also for drilling areas in Cypriot waters. On at least one occasion, Israeli warplanes have confronted Turkish ships.

Such clear signals of resolve are welcome. As the European Union pushes Greece to drill for hydrocarbons to find new sources of income, it should also support Athens declaring its EEZ, reject AKP troublemaking vis-à-vis Kastelorizo, and clearly indicate the dire results for Turkey of any trouble-making toward an island now happily renowned for its diving and snorkeling.