It's Not Road Rage, It's Terrorism

On February 25, 1994, Baruch Goldstein, an Israeli doctor of American origins, went to the mosque at the Cave of the Patriarchs in Hebron, and murdered twenty-nine Muslims with an automatic weapon before being overwhelmed and himself killed. This massacre prompted conspiracy theories and riots in Muslim circles, including accusations that the government of Israel stood behind Goldstein, an allegation that strenuous denunciations of his attack by the Israeli government did not fully deflect.

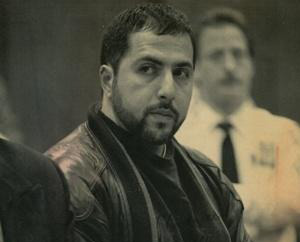

Rashid Baz, who attacked a Jewish target in New York City in 1994.

On March 1, four days later, Rashid Baz, a New York livery driver of Lebanese origins, fired two guns at a van carrying Hasidic Jewish boys on a ramp leading to the Brooklyn Bridge, killing Ari Halberstam, 16, a yeshiva student. Baz was quickly apprehended, convicted, and sentenced to 141 years in prison. Circumstantial evidence pointed to a link between the two events, for Baz was immersed in the Arabic-language media coverage of Goldstein's attack, he attended the incendiary Islamic Center of Bay Ridge, and he was surrounded by Muslims who condoned terrorism against Jews. More than that, friends indicated that Baz was obsessively angered by the attack in Hebron and the psychiatrist for his legal defense, Douglas Anderson, testified that Baz "was enraged" by it. "He was absolutely furious. ... Were it not for Hebron this whole tragedy [in New York] wouldn't have occurred."

Yet the seemingly obvious connection between Goldstein and Baz could not be established because Baz accounted for his violence by referring to post-traumatic stresses from his experiences in Lebanon. And so, despite the preponderance of evidence, the Federal Bureau of Investigation adopted Baz's own dissemblance and called the murder on the Brooklyn Bridge an act of "road rage." Only after Halberstam's mother devoted years of effort did the FBI in 2000 reclassify the Baz attack as terrorism.

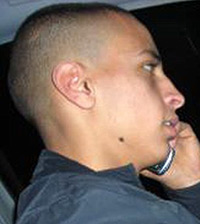

Mohammed Merah, who attacked a Jewish target in Toulouse in 2012.

And thus matters rested until a few days ago, when Baz's confession in 2007 finally became public via a New York Post article. In it, Baz acknowledged the impact of the Goldstein atrocity on him, admitted having specifically targeted Jews, and confessed to following a van of Hasidic boys for two miles from the Manhattan Eye and Ear Infirmary to the bridge. Asked if he would have shot at a van full of black or Latino people, he replied, "No, I only shot them because they were Jewish."

This belated confession points to a recurring problem of politicians, law enforcement, and the press with Islamist terrorism: their unwillingness to stare it in the face and ascribe murder to it.

Most recently, this avoidance reared its ugly head in the case of Mohammed Merah in Toulouse, France, where the establishment's immediate impulse was to assume the murderer of three soldiers and four Jews was a non-Muslim. As my colleague Adam Turner notes in the Daily Caller, "the elite Western public officials' and media's speculation about the true killer, prior to the discovery of his identity, heavily focused (also here and here and here) on the belief that he was a white European neo-Nazi." Only when Merah himself boasted of his crime to the police and even sent videos of his actions to Al Jazeera did the other theories finally vaporize.

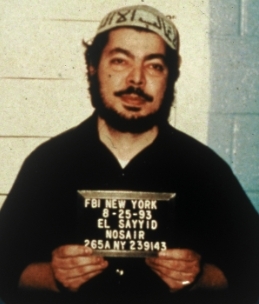

El Sayyid Nosair, who attacked a Jewish target in New York City in 1990.

The Baz and Merah examples fit a much larger pattern of denying Islamist terrorism that I trace as far back as the 1990 assassination of Rabbi Meir Kahane in New York City by El Sayyid Nosair, an attack initially ascribed by the police department's chief of detectives to "a prescription drug for or consistent with depression." Since then, time and again, the establishment has conjured up similarly lame excuses for Islamist terrorism, including "a work dispute," a "stormy [family] relationship," the acne drug Accutane, an "attitude problem," and "loneliness and depression."

Most disturbing, however, is the tendency to ascribe Islamist terror to diminished mental capacity. As Teri Blumenfeld notes in the current issue of the Middle East Quarterly, "Muslims who kill in the name of their religion frequently evade punishment in Western courts by pleading insanity or mental incompetence." In Western courts, indeed, defense lawyers routinely attribute acts of jihadi murder to insanity.

Ignoring the religious and ideological roots of Islamist terrorism carries a heavy price; not thoroughly investigating the Kahane assassination meant overlooking materials that could have prevented the World Trade Center bombing in 1993; and Merah's apprehension sooner would have saved lives. Islamism must be squarely faced to protect ourselves from future violence.