The 2012 Election: Freedom, Justice, Fairness, and Opportunity

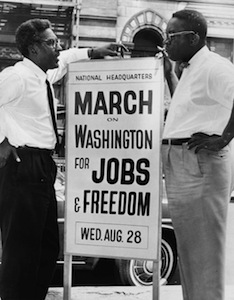

Bayard Rustin and Cleveland Robinson confer before the 1963 March on Washington. Credit: Library of Congress/New York World-Telegram.

Now that the Republican ticket is set with Mitt Romney's selection of Paul Ryan as his vice-presidential choice, it's time to compare the rival tickets regarding some basic values.

Let's start with freedom. Among others, U.S. historian David Hackett Fischer has stressed what an essential value it has been to us and how differently we have interpreted it. In his Liberty and Freedom he indicated that even these two synonyms have often taken on different shades of meaning.

In his Conservatism in America, historian Clinton Rossiter once noted that "the preference for liberty over equality lies at the root of the Conservative tradition, and men who subscribe to this tradition never tire of warning against the 'rage for equality.'" At the end of the twentieth century, conservative historian Richard Pipes echoed that sentiment in Property and Freedom, where he wrote that "the main threat to freedom today comes not from tyranny but equality -- equality defined as identity of reward." He also stated that programs such as affirmative action and school busing impinged upon freedom and that "the entire concept of the welfare state ... is incompatible with individual liberty."

When today's conservatives speak of freedom they usually mean from big government and from "high" taxes. In a 2009 speech Paul Ryan, who has more recently proposed even more favorable tax policies for the rich than now exist, warned of the danger of turning "over our government to health bureaucrats, industrial policy bureaucrats, education bureaucrats, housing bureaucrats, energy bureaucrats, and family control bureaucrats -- a road [Friedrich von] Hayek perfectly described as 'the road to serfdom.'"

Ryan has often quoted Hayek and acknowledged his debt to him (see here for more on Hayek and Republicans). In books such as Road to Serfdom (1944), The Constitution of Liberty (1960), and the 3-volume Law, Legislation, and Liberty (1973-79), the Austrian-born economist criticized any attempt by governments to redistribute wealth, for example to aid the poor. Hayek believed that to maintain freedom, free-market capitalism had to be allowed to operate unfettered. Government officials who disrupted the spontaneous economic order in the name of "social justice" (which Hayek labeled a mirage) were to him a great threat to freedom.

But liberals have a different view of freedom. In his most recent book, Fairness and Freedom: A History of Two Open Societies—New Zealand and the United States, Fischer writes about Roosevelt's New Deal: "Always its primary goal was a larger idea of individual freedom for Americans." A year before his death, Roosevelt (in his 1944 State of the Union Address to Congress), said, "freedom cannot exist without economic security and independence. 'Necessitious men are not free men.'" And he called for a "second Bill of Rights" that would include "the right to a useful and remunerative job"; "the right to earn enough to provide adequate food and clothing and recreation"; "the right of every family to a decent home"; "the right to adequate medical care"; "the right to adequate protection from the economic fears of old age, sickness, accident, and unemployment"; and "the right to a good education."

Decades later, economist Amartya Sen wrote in his Development as Freedom (1999) that true freedom required not just political and civil rights, but also "substantive freedom." This meant economic and social opportunities such as jobs and subsidies, unemployment benefits, and inexpensive health care. Poor, uneducated people without land, jobs, or access to health care, might be free to associate with whomever they please and to vote and exercise other personal and civic rights, but Sen argued that they were not as free as those who possessed many more opportunities due to their greater resources. A contemporary of Sen, Martha Nussbaum, made a similar point when she declared "liberty is not just a matter of having rights on paper, it requires being in a position to exercise those rights. And this requires material and institutional resources."

Obviously, to provide the type of opportunities Sen and Nussbaum write about takes government revenue. In his most recent book, So Rich, So Poor: Why It's So Hard to End Poverty in America, Peter Edelman writes, "The first thing we need to do is roll back the Bush tax cuts for the wealthy. If we can't do that, we're not going to have the resources to do the next ten things" to significantly lessen poverty. To the Romney-Ryan ticket such a liberal approach to freedom is anathema. Lessening "big government" and taxes is their primary freedom criteria. (For more on their opposition to various kinds of civil liberties, see here.)

Next, let us examine the concept of justice. Our Constitution begins with the words "We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice...." In our Pledge of Allegiance we speak of "liberty and justice for all." Unlike the Romney-Ryan team, President Obama has placed much emphasis on justice. Unlike Ryan, who has been so greatly influenced by Hayek, who considers social justice a myth, Obama's concept of justice owes much to John Rawls. In his A Theory of Justice (1971) and other writings he outlined what he believed was the proper balance between liberty and justice.

In working out his theory of "justice as fairness," Rawls tried to get us to consider justice impartially by imagining ourselves devoid of any knowledge of our own characteristics and status -- wealth, education, talents, etc. He called this "the veil of ignorance." If we put ourselves in such an unbiased position, he argues, the most rational approach to justice would be to establish two principles of justice. The first "requires equality in the assignment of basic rights and duties," while the second holds that "social and economic inequalities, for example inequalities of wealth and authority, are just only if they result in compensating benefits for everyone, and in particular for the least advantaged members of the society."

In his Reading Obama (2011) historian James T. Kloppenberg cites these principles and depicts Rawls as the major intellectual influence on legal thinking while Obama was earning a degree at Harvard Law School. And the historian adds that "to a remarkable degree, Rawls's two principles align with the principles that Obama learned in Chicago as a community organizer. ... It is the people at the bottom of the heap, the people who lack the resources to realize their life plans, who should be the focus of social policy. Democratic government should concentrate its resources not on rewarding the powerful but on improving the situation of the least advantaged."

That President Obama perceives fairness as essential to justice is without doubt. In a September 2011 opinion piece in the Washington Post, conservative Michael Gerson noted that Obama in a Rose Garden statement about the American Jobs Act "employed variants of the word 'fair' at least 10 times." Among other things, he said "I will veto any bill that changes benefits for those who rely on Medicare but does not raise serious revenues by asking the wealthiest Americans or biggest corporations to pay their fair share. We are not going to have a one-sided deal that hurts the folks who are most vulnerable." Referring to the ongoing debate with Republicans about the economy, jobs, government spending and deficit reduction, the president ended his remarks by saying that the debate was "also about fairness. It's about whether we are, in fact, in this together, and we're looking out for one another. We know what's right. It's time to do what's right."

In a speech in Kansas on December 6, 2011, the president spoke of the progressive ideas of Teddy Roosevelt a century earlier and about growing economic inequality. And again he emphasized fairness, calling for "rebuilding this economy based on fair play, a fair shot, and a fair share." The president's State of the Union speech in January 2012 again emphasized fairness.

In an August 12, 2012 New York Times opinion piece, philosopher Benjamin Hale wrote extensively on Rawls, justice, fairness and this year's election: "As this election season wears on, we will likely be hearing a lot about fairness. Romney recently signaled as much. Obama has been doing so for months. ... The question of fairness has widespread application throughout our political discourse. It affects taxation, health care, education, social safety nets and so on." "The veil of opulence [Hale's term for Romney's view of fairness] "would have us screen for fairness by asking what the most fortunate among us are willing to bear. The veil of ignorance [the Rawls-Obama approach] "would have us screen for fairness by asking what any of us would be willing to bear, if it were the case that we, or the ones we love, might be born into difficult circumstances or, despite our hard work, blindsided by misfortune." Hale leaves no doubt that he considers the Romney view a bogus approach to fairness.

The article Hale cites about Romney's view of fairness makes it clear why: "He believes that fairness is defined by market outcomes. If Romney earns a thousand times as much as a nurse in Topeka, it is solely because his character, education, or hard work entitle him to that. To the extent that unfairness exists, it is solely the doing of government: clean energy, laws permitting union dues, overpaid government employees, and so on. Aside from unfairness imposed by government, poverty is attributable to the bad choices or deficient character or upbringing of poor people."

In historian Fischer's most recent book, he contrasts the views of Roosevelt on fairness with that of "conservative Republicans [who] saw the New Deal as hostile to capitalism and private property." Rather than responding to it and hard economic times in our present century "with reasoned moderation, sympathy for the suffering poor, constructive compromise, and a willingness to act for the common good," Fischer writes that "conservatives in America went the other way in the 1930s, and again in the early twenty-first century."

The relationship between fairness, as Rawls outlined it, and opportunity is not difficult to perceive. Without adequate funding of government policies designed to create more equal opportunity (e.g., Head Start, which would suffer under a Romny-Ryan administration), the opportunity gap between rich and poor would become even worse than it is at present.

Even conservative columnist David Brooks recognizes this. In a recent piece entitled "The Opportunity Gap" he wrote about "inequality of opportunities among children," which has gotten much worse in recent decades. He continues, "Equal opportunity, once core to the nation's identity, is now a tertiary concern."

Liberals, of course, have long been troubled by this growing chasm. In a recent essay and book, both entitled "The Price of Inequality," economist Joseph E. Stiglitz states the case clearly. In his article he writes, "America likes to think of itself as a land of opportunity, and others view it in much the same light. But, while we can all think of examples of Americans who rose to the top on their own, what really matters are the statistics: to what extent do an individual's life chances depend on the income and education of his or her parents? Nowadays, these numbers show that the American dream is a myth. There is less equality of opportunity in the United States today than there is in Europe -- or, indeed, in any advanced industrial country for which there are data."

What is troubling is that most conservatives still believe that the chief way to more equality of opportunity is cutting back on government programs and reducing taxes, especially for the wealthy. In the Washington Post piece mentioned above, Gerson (who was a major speech writer for George W. Bush) states that "Rawls's conception of fairness provided a moral justification for an expansive welfare state. It also reinforced an assumption among liberals that all reasonable people are egalitarians."

Like Hayek, Pipes, Paul Ryan, and conservatives generally, Gerson believes that expansive government programs limit, rather than expand, freedom of opportunity. And he is mistaken if he believes Rawls or Obama are advocating equality of results ("identity of reward" in Pipes's phrase) rather than equality of opportunity. He follows up his criticism of the Rawls-Obama conception of justice as fairness with the following words: "There is, however, another tradition of American political thought: a belief in justice as opportunity. Instead of focusing on the fair distribution of wealth in a static economy, presidents such as Abraham Lincoln and Ronald Reagan set out to increase the economic rewards for enterprise and ambition. . . . They talked not just of equality for those at the bottom of the social ladder but of a chance to rise upon it. ... In a free society, the most important goal is not a fair outcome but a fair chance -- not economic equality but social mobility in a dynamic economy."

If Gerson really believes that the type of policies advocated by the Tea Party or Romney-Ryan would further opportunities for the majority of people in our country, he is woefully wrong. Not only would they reduce such opportunities, so too would they reduce freedom (in the fullest sense of the word), justice, and fairness.