Why Aren’t We More Worried About Pandemics?

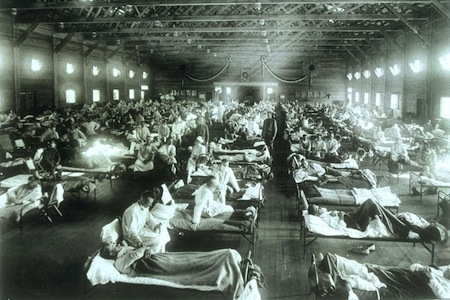

Soldiers from Fort Riley, Kansas, in a hospital ward ill with Spanish Flu. Credit: U.S. Army/Wikimedia Commons.

As the First World War entered its closing stages, a terrifying new virus swept across the world, killing more people than the conflict itself. The disease may have emerged in Kansas, in January 1918. By March it had reached the U.S. Army camp Fort Riley, with hundreds of troops reporting sick. The shipment of troops to Europe may have spread the virus there and beyond. With near simultaneous reported outbreaks of the disease in Europe, Africa and elsewhere in America, and a possible earlier outbreak in Austria, we may never know the exact origin of the deadly virus. The total number of deaths caused by the pandemic as it spread around the world is now estimated to be between 50 and 100 million, whereas the number of deaths caused by the Great War is generally accepted to be around 16.5 million, and a significant number of these deaths were caused, in 1918, by the disease itself. Communities were completely blindsided by the outbreak of the disease, and felt -- as did the victims of the Black Death in the Middle Ages -- that the world (or at least civilization) was coming to an end.

As the First World War entered its closing stages, a terrifying new virus swept across the world, killing more people than the conflict itself. The disease may have emerged in Kansas, in January 1918. By March it had reached the U.S. Army camp Fort Riley, with hundreds of troops reporting sick. The shipment of troops to Europe may have spread the virus there and beyond. With near simultaneous reported outbreaks of the disease in Europe, Africa and elsewhere in America, and a possible earlier outbreak in Austria, we may never know the exact origin of the deadly virus. The total number of deaths caused by the pandemic as it spread around the world is now estimated to be between 50 and 100 million, whereas the number of deaths caused by the Great War is generally accepted to be around 16.5 million, and a significant number of these deaths were caused, in 1918, by the disease itself. Communities were completely blindsided by the outbreak of the disease, and felt -- as did the victims of the Black Death in the Middle Ages -- that the world (or at least civilization) was coming to an end.

Should we be worried about the outbreak of another vicious pandemic that may kill us by the millions? Yes, we should.

There will be, without a shadow of doubt, new viral pandemics that kill huge numbers of people around the world, facilitated by the dramatic and relatively recent rise of global air travel.

Will we actually fret about this on a daily basis? No, we will not.

Should we? Well, possibly not.

Neuroscience is beginning to reveal why we are so unrealistically optimistic -- for intriguingly positive adaptive reasons. And luckily, since we are not just an unreasonably optimistic but also a very clever species, we have a potential solution up our sleeves: the supra-human organisation.

Spanish Flu

The 1918-19 pandemic came to be known as "Spanish Flu" only because Spain was not a combatant in the war and had not imposed press censorship. Combatant countries were not about to tell the enemy that soldiers and civilians were dying in large numbers from an outbreak of a mysterious, killer virus. The world did, however, learn that King Alfonso XIII of Spain was suffering from an illness that was also affecting many of his subjects, and the term "Spanish Flu" was born.

While the earliest, first wave of infections by the new influenza virus was relatively benign, the next wave was unbelievably deadly. Doctors thought that patients were presenting symptoms not of influenza, but of dengue fever, cholera, or typhoid. Patients hemorrhaged blood from the nose, stomach and intestines; from ears, beneath the skin and inside the eye. Some were partially or even completely paralysed. The disease also caused a rapid and catastrophic failure of the lungs. Patients turned blue and died within hours.

As the disease in its most virulent form spread across the world it seemed as if the Black Death had returned. In many American towns and cities panic set in, made worse by the fact that it was public policy to deny that there was an epidemic. The public health commissioner of Chicago said, in 1918, "It is our duty to keep people from fear. Worry kills more people than the epidemic." People were prevented neither form worrying nor from dying. In Chicago’s Cook County Hospital, 40 percent of all influenza admissions died. In Philadelphia, dead bodies remained for days in houses without being collected. Eventually, trucks and horse-drawn wagons were sent out and the call of, "Bring out your dead!" was heard on the streets of America in the twentieth century. As with the Black Death, neighbors refused to help stricken neighbours; a society that prided itself in neighborliness began to fall apart. The Red Cross in Kentucky reported that people suffering from the disease were starving to death because their neighbors were too frightened to take food to them. Another Red Cross report wrote that, "A fear and panic of the influenza, akin to the terror of the Middle Ages regarding the Black Plague, [has] been prevalent in many parts of the country." There were very real fears that society, and civilization, were on the brink of collapse.

Viruses can "jump species" to humans: birds and pigs are the most likely source. These viruses tend to make us very ill, because our immune systems do not recognize them, but they are unable to spread from human to human. The real risk comes if a victim is infected simultaneously by both human flu and bird or pig flu, allowing the two viruses to exchange genetic material. Now we have a virus that can be transmitted from human to human: we have an epidemic. It is inconceivable, in an age of unprecedented global travel, that we will not suffer another pandemic at some point in the future, probably relatively soon.

So, why are we not more worried?

The neuroscience of unreasonable optimism

A study led by Tali Sharot explored the neuroscience of "unreasonable optimism" and showed that our brains have a built-in tendency to focus on good news, and to suppress bad news. Let’s say that you think that your chances of getting cancer in your lifetime are 40 percent. If you are then told that the average figure for people from the same socio-cultural environment as yourself is actually 30 percent, then your conscious mind wakes up and takes note. "Jolly good!," it thinks. And when asked on a second occasion what the probability of contracting cancer might be, the subjects in this experiment tended to confirm that their personal likelihood of getting cancer was more like 30 percent. But in cases where we had underestimated the chance of getting cancer -- perhaps at only 10 percent -- and are then given the bad news, then our brains are far less interested. To use the neuroscientist’s own words, there is "diminished coding of undesirable information about the future." Our brains, whether we like it or not, seize on good news about what may happen to us and tend to discount bad news. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to pick out the areas of the brain that are most active while we process information like this, neuroscience reveals that is essentially our emotional, pre-conscious brain that it taking care of businesses when we are presented with information that makes us stressed and unhappy. We are not really "taking decisions" about such information at all; the brain merely declines to process it. The good news is that this keeps us in good mental and physical shape to face the challenges that life puts in our way. The bad news is that, we tend to underestimate the likelihood of bad news, and are frequently blindsided when something quite likely but very unpleasant actually happens to us.

There are benefits in this: "Underestimating susceptibility to negative events can serve as an adaptive function by enhancing explorative behaviour and reducing stress and anxiety associated with negative expectations." Put another way, we would all be gibbering wrecks if we faced, every minute of our waking lives, the reality of the bad stuff that is likely to happen to us. So we don’t.

What we do, because we are clever animals, is to set up organizations like the World Health Organization, part of the United Nations, that do spend all of their time worrying about things like the next flu pandemic. The UN is funded by assessed voluntary contributions and the U.S. is the world’s largest contributor. Every year, the contribution is voted through by Congress, who recently and very sensibly passed legislation requiring the administration to report annually to Congress on the amount of U.S. money being contributed to the UN and for what purposes. If anybody asks you if you think that U.S. money to fund the UN’s World Health Organization is well-spent, just say "Yes!"