What Would a Mitt Romney Foreign Policy Look Like?

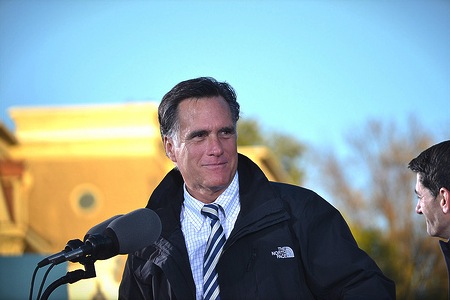

Mitt Romney and Paul Ryan at a rally in Lancaster, Ohio. Credit: Flickr/Robert Batina.

Massachusetts governor and GOP presidential candidate Mitt Romney gave a foreign policy-centric address at the Virginia Military Institute [VMI] on October 8; his running mate, Congressman Paul Ryan, opined at some length -- when Vice-President Joe Biden would let him speak -- on foreign policy during the VP debate on October 11. While the Romney-Ryan positions on international affairs are spelled out on the campaign website, getting the information straight from the elephants’ mouths can often prove more enlightening -- and taken together, these two public addresses provide evidence of potentially surprising strengths, as well as troubling weaknesses, should these two men win next month.

At VMI, Romney worked to his audience by invoking perhaps that institution’s most famous graduate, General and later Secretary of State and Defense George Marshall, who was complimented by Churchill for fighting against “defeatism, discouragement and disillusion” -- three problems which Romney sees the Obama administration as having fostered. Of course, Romney then segued into the anti-American violence in Libya and other Muslim-majority countries, upon which he promised to “offer a larger persepective.” To that end, Romney shaped his talk around three themes: the ostensible yearning for American-style freedom among the peoples of the Middle East; the alleged lack of leadership from the Obama administration, and how he would rectify that; and, finally, the invocation of “extremism” as the explanation for the anti-Americanism in the Islamic world.

Ironically, rather like Obama, Romney sees the events of the “Arab Spring” and the abortive “Green Revolution” in Iran through neo-Wilsonian lenses, as evidence of Middle Eastern masses yearning to breathe free -- a “struggle between liberty and tyranny, justice and oppression, hope and despair.” In this Manichaean conflict, Romney turns the Obama administration’s own phrase describing its Libya policy -- “leading from behind” -- against the president and uses it as a base from which to construct a multi-level critique of current policy:

1) Obama’s distancing of the U.S. from its traditional ally Israel has “emboldened our mutual adversaries, especially Iran;”

2) the Islamic Republic of Iran “has never been closer to a nuclear weapons capability” and “has never acted less deterred by America;”

3) Iraq faces “rising violence, a resurgent al-Qaeda, the weakening of democracy in Baghdad, and the rising influence of Iran;”

4) the Syrian regime is slaughtering its own people; and

5) the president’s over-reliance on stand-off drone strikes is “no substitute for a national security strategy for the Middle East.”

Romney continued: “I know the president hopes for a safer, freer and more prosperous Middle East allied with the United States. I share this hope. But hope is not a strategy.” It’s far from clear that frosty U.S.-Israeli relations have emboldened the ayatollahs, considering they may well see such as wily “Zionist subterfuge,” but as someone who studies Iran, and has even been there, I think it’s undeniable that the Islamic Republic of Iran fears Obama far less than his predecessor, who invaded both neighboring countries. As for Iraq’s problems, none is really Obama’s fault and in fact one might well argue that Tehran’s influence there amounts, rather, to a reassertion of the centuries-old fault line between (Ottoman) Sunni and (Persian) Shi`i cultural zones. The al-Assad, Alawi regime in Syria is slaughtering Sunni militas -- but whether that’s worse, geopolitically, than having the Salafi-heavy opposition groups and their AQ allies taking over Damascus is debatable. I do think Romney is on solid ground in his claim that foreign-policy-by-Predator is less than ideal, however; Obama’s drone strikes are far more numerous than Bush’s, and while they do keep Americans out of harm’s way one suspects that were a Republican administration killling as many civilians via this mode as it does “militants” that the media would be giving the issue far more coverage. It’s also worth noting that dead (suspected) terrrorists are rather poor sources of intelligence -- although they do keep the politically inconvenient ranks of Gitmo detainees lower.

Over against these alleged inadequacies in the current administration’s approach, Romney presented his policy proposals:

1) new sanctions and the credible threat of U.S. military action to curb Iran’s nuclear weapons quest;

2) recommitment to Israel;

3) “deepen[ing] our critical cooperation with our partners in the Gulf” (although whether this means the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, the smaller Emirates and such -- or both -- is left unspecified);

4) quixotically, no doubt, importuning NATO allies to increase defense spending;

5) creating what sounds like a Middle East czar -- or, perhaps more accurately, sultan -- to oversee policy in that region;

6) matching U.S. aid to not just protection of diplomats but “civil society, a free media, political parties, and an independent judiciary;”

7) being a “champion of free trade;”

8) rather blandly, “support[ing] friends across the Middle East who share our values” in Libya, Egypt, Syria and Afghanistan; and finally

9) “recommit[ing] America to the goal of a democratic, prosperous Palestinian state living side by side in peace and security with the Jewish state of Israel.”

Most of these are rather standard-issue conservative foreign-policy boilerplate, manifesting Romney’s rather prudent -- some would say risk-averse, bordering on timid -- approach to winning this election: “first, do no harm (to your potential independent vote).” And in fact, the fifth one sounds strangely bureaucratic and, dare I say it, liberal for the GOP nominee. At least Romney made some attempt to make U.S. foreign aid contingent on, for example, the recipient country actually keeping our ambassador alive -- unlike the current president. But the bottom-line seems to be that Romney is running, with good reason, on the Clintonian (Carvillean, actually) dictum “it’s the economy, stupid” and hoping to avoid the foreign policy thicket until after January 20, 2013.

Throughout this dual litany of Obama policy mis-steps, on the one hand, and his own preferred changes, on the other, Romney adduced the term “extremism” no fewer than seven times:

1) “mobs hoisted the black banner of Islamic extremism over American embassies;”

2) “the very extremists who murdered our people” in Benghazi;

3) in Syria “violent extremists are flowing into the fight;”

4) besides al-Qaeda, “other extremists have gained ground acros the region;”

5) “violent extremists [are] on the march;”

6) in the Middle East, we have “friends who are fighting for their futures against the very same violent extremists;” and, finally,

7) the Obama 2014 pull-out from Afghanistan “abandons the Afghan people to the same extremists who ravaged their country.”

Only once, note, did he preface the term with the adjective “Islamic.” However, by that one example of intellectual honesty, Romney locates himself light-years ahead of the Obama administration, which actively discourages honest discussion of the fact that 61 percent -- 31 of 51 -- of the foreign terrorist organizations on the State Depatment’s list thereof are Islamic and which, further, sanctions counter-terrorist trainers who dare to utter words such as “jihad.” One wishes he would simply call an Islamic extremist spade a spade -- but Romney is allowing himself to be constrained by his stable of advisors, as well as, perhaps, the pro-Islamic tendencies inherent in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. Someone needs to tell the Governor that naming Islamic extremism in the defense of Western civilization is no vice.

The vice-presidential debate, by contrast with Romney’s enlightening (if only wanly) speech, provided a great deal of heat but little light -- and since it was often almost impossible to disentangle Paul Ryan’s points from Joe Biden’s interruptions, the sitting VP’s foreign policy positions (or a least statements) will be analyzed here, as well. For all his later bluster, Biden was curiously passive in his intitial utterances on Libya, calling the killing of Ambassador Stevens a “tragedy” rather than an attack, and waxing Clintonian with “whatever mistakes were made will not be made again.” He then of course lionized his boss for “get[ting] bin Laden,” and accused Ryan’s boss of wanting to start “another war” -- presumably with Iran. Ryan responded by saying the GOP ticket agreed with the 2014 deadline for withdrawal from Afghanistan, but said they wanted to “make sure that we’re not projecting weakness abroad.” When the congressman claimed that “what we are watching on our TV screens is the unraveling of the Obama foreign policy,” moderator Martha Raddatz hammered him with “you’re talking about this again….the [Obama] weakness….Was that really appropriate right in the middle of the crisis?” Ryan pointed out the that administration had had to disavow apologetic statements from their own diplomats in Cairo, and that Romney had merely done the same thing -- just hours earlier. He then accused the administration on failing to speak out on behalf of the “Green Revolution” in Iran, of calling Bashar al-Assad a “reformer” (which Secretary of State Hillary Clinton did do some 18 months ago) and of planning “devastating defense cuts.”

When Raddatz confronted Biden (one of the few times she did so) on the issue of what the administration knew about the embassy attack in Benghazi, and when they knew it, Biden blustered and blamed the intelligence community for the White House claiming that a Muhammad-video-incensed mob, rather than Ansar al-Shari`ah (an AQ affiliate), perpetrated the violence. And the entire world knows by now that the VP also denied that the administration was asked by the embassy in Libya for more security personnel.

In what was perhaps the most troubling part of the debate for Ryan, Raddatz asked “should the U.S. have apologized for American burning Korans [sic] in Afghanistan? Should the U.S. apologize for U.S. Marines urinating on Taliban corpses?” Ryan responded “Oh, gosh, yes.” But then continued “what we should not be apologizing for are [sic] standing up for our values….saying to the Egyptian people, while Mubarak is cracking down on them, that he’s a good guy and, in the next week, say he ought to go.” He never answered whether the U.S. should apologize for burning Qur’ans, but the tone and context strongly implied he believed that it was of a part with urinating on dead jihadists, and thus presumably worthy of contrition on by America. Strange, and disturbing -- considering that burning Qur’ans is actually allowable under Islamic law and under the conditions existing at the Parwan detention facility in Afghanistan back in February, 2012. Ryan seems to be accepting the liberal and frankly dhimmistic view that Islamic strictures should apply to non-Muslims. If so, what separates him from the likes of Biden and Obama?

Regarding the next topic, Iran, both Biden and Ryan misspoke. Ryan hyperbolized by claiming that Iran already has enough fissile material to make five bombs -- in reality, they likely don’t have enough for one yet. Biden wildly exaggerated by describing the current sanctions on Iran as “the most crippling…in the history of sanctions, period.” The VP seems never to have heard of what the Spartans did to the Athenians, the Union to the Confederacy or the U.S. to Cuba during the Cuban Missile Crisis. (But, of course, Joe Biden is the same fellow who called the killing of bin Laden “the most audacious military plan of the last five hundred years.” Inchon? Blitzkrieg? Waterloo? Naseby? Tenochtitlan? Vienna? Did Biden ever study history?) The sitting VP also claimed that even if Iran were to produce enough fissile material for a bomb, “they don’t have a weapon to put it into.” But over a year ago the British Foreign Secretary said that they had intelligence confirming the Iranians had tested “nuclear-capable missiles.” Biden closed this topic by accusing the Romney-Ryan ticket of wanting to start another war in the Middle East.

After a long discussion of domestic spending, Raddatz moved back to the topic of Afghanistan. She noted that we just recently passed 2,000 U.S. military fatalities there, and that this year alone so far 50 Americans have been killed by the very people we are trying to help. So she asked Ryan “why not leave now? What more can we really accomplish?” Ryan responded that “we want to make sure that the Taliban does not come back in and give Al Qaida [sic] a safe haven” and questioned the wisdom of the administration’s policy, for some time, of negotiating with the Taliban. VP Biden riposted that “we went there for one reason: to get those people who killed Americans, Al Qaida. We’ve decimated Al Qaida central. We have eliminated Osama bin Laden.” Other than not seeming to know the original meaning of “decimate,” I thought that Biden got the better of this exchange, not least because Ryan’s earlier statements that he and Romney agreed with the 2014 withdrawal date rather vitiated his attempted points here.

Next Raddatz turned to Syria. Trenchantly, she drilled the VP on why the U.S. supported military action against al-Qadhafi, but not against al-Assad. Biden tried to differentiate the two cases by noting the much smaller size and larger population of Syria, as well as its central location in the Middle East (vis-à-vis Libya), but then undermined his own argument by setting up the straw man topic of introducing ground troops -- which Ryan jumped on by pointing out “nobody is proposing to send troops to Syria.” Ryan, however, after that strong opening trailed off into rather weak and irrelevant objections such as saying “we wouldn’t refer to Assad as a reformer” or “outsourc[e] our foreign policy to the United Nations.” Puzzlingly, Raddatz then asked Ryan “what happens if Assad does not fall?” Shouldn’t that question have been asked of the current VP, not the aspiring one? In any event, Ryan responded quite accurately “then Iran keeps their [sic] greatest ally in the region.” The moderator then asked Ryan—but not, again quite curiously, the current VP -- his criteria for (military) intervention, not just in Syria but “worldwide.” Ryan responded “what is in the national interest of the American people.” Pressed by Raddatz on “humanitarian interests,” the GOP VP candidate replied “that means embargoes and sanctions and overflights…but if you’re talking about putting American troops on the ground, only in our national security interests.” Later, right before the closing statements, Biden attempted to blame Ryan and the GOP Congress for the deficits by “vot[ing] to put two wars on a credit card” -- a charge made rather hollow by the fact that Biden voted in favor of both the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, as well as the fact that Obama’s record one-term addition to the national debt of $5 trillion took place while one of those wars, Iraq, was ending.

The CNN Candy Crowley-conducted second presidential debate, billed as a town hall that would focus on both domestic and foreign policy, contained a grand total of one question on the latter -- about Libya. Most of the “answer” to that question consisted of President Obama and Governor Romney sparring about when the president actually employed the term “terrorism” to describe what happened to our ambassador and the other Americans killed in Benghazi. But in-between verbal barbs, Mr. Obama managed to work in that he’s ended the war in Iraq, is terminating the one in Afghanistan, and of course that he sent Osama bin Laden to meet those 72 houris. Mr. Romney riposted by listing Libya, Egypt, Syria and Iran as evidence of administration failures in the Middle East -- without really explaining how and why. Other than an opaque Romney disquisition on Chinese currency manipulation, that was it for the foreign policy part of this debate. (Unless one counts the mind-numbingly uninformed discussion about AK-47s and “assault rifles” as a foreign affairs issue -- they are, after all, Soviet Russian weapons, at least originally.) However, the third and final presidential debate next week is slated to deal entirely with non-domestic issues. Hopefully, CBS’s Bob Schieffer will moderate a debate which will finally, effectively illuminate the differences between Romney and Obama on foreign policy in general and approaches to the Islamic world and Islamic terrorism, in particular.

What can we learn about a potential Romney-Ryan Administration foreign policy in general, and its approach to the Islamic world, in particular, from the VMI speech and the lone VP debate, and the second presidential debate? Geostrategically, and most importantly, the GOP presidential candidate does seem to recognize the need to combat and reverse the American Great Power decline, not simply manage (and indeed foster?) it, as Obama seems content to do -- in Romney’s opposition to “defeatism, discouragement and disillusion.” (For those, especially on the Left, who would welcome the continued humbling of the former “hyperpower,” I suggest a reading of Niall Ferguson’s historically-embedded review of past periods of “a-polarity” in world history -- “dark ages” lacking a powerful hegemon.) Ryan’s articulation of national security interests as being the sine qua non for U.S. boots on the ground in any foreign conflict seems to place the prospective GOP administration squarely in the realist school of international relations—albeit tempered by a (Catholic, in his case?) acknowledgement of humanitarian concerns as a crucial factor, as well. And a Romney administration would certainly restore America’s traditional close relationship with Israel.

On the negative side of the ledger, the Governor’s nattering about “extremism,” almost always sans the important and accurate modifier “Islamic” -- who, after all, outside of Hollywood and faculty lounges is concerned about Christian (or Hindu or Sikh or Buddhist) “extremism” -- worryingly echoes Obama adminstration propaganda. Especially when paired with Congressman Ryan’s seeming willingness to accede to Muslim strictures on Qur’anic inviolability and curious concern for the honor of dead jihadists, Romney’s political correctness regarding the most pressing security issue of the early twenty-first century is disheartening. Increasingly, it’s becoming clear that the “Arab Spring” was, and is, not about aspirations to Jeffersonian democracy but rather the resurgence of pro-Shari`ah tendencies among the Arab Muslim masses. Whether a President Romney would be able to recognize, or even acknowledge, that inconvenient truth -- and find more effective ways than Obama to deal with it--is a question that someone needs to ask in the final presidential debate.