Ninety-Five Years Since the Balfour Declaration

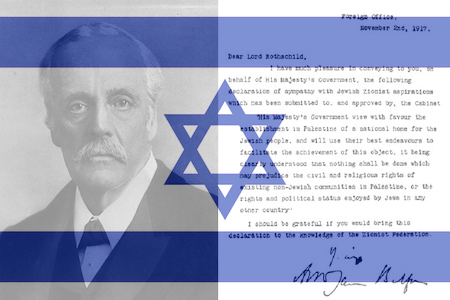

Lord Balfour and his declaration. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

A mere sixty-eight words helped alter the course of history. Ninety-five years ago (as of November 2), the British Foreign Secretary, Arthur James, Lord Balfour, sent the following communication to Walter, Lord Rothschild, one of the most prominent Jews in England, for transmission to the Zionist Federation of Great Britain and Ireland:

His Majesty's government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.

It is difficult to isolate a single motive for the issuance of the Balfour Declaration. Balfour himself, undistinguished by philo-Semitism prior to acquiring his deep interest in Zionism from Zionist leader Chaim Weizmann, was enamored of the ideal of righting the historical tragedy of Jewish statelessness, with the propellant force of British imperial might and political idealism behind him. But it is harder to detect such motivations in most of his colleagues, who focussed more on proximate interests that the Declaration might help to secure in the war.

For all that, the British decided upon the Declaration in full knowledge of the undertaking. Norman Bentwich, the first Attorney-General under the Mandate, later said, “The Balfour Declaration was not an impetuous or sentimental act of the British government, as has been sometimes represented, or a calculated measure of political warfare. It was a deliberate decision of British policy and idealist politics, weighed and reweighed, and adopted only after full consultation with the United States and with other Allied Nations.”

The British commitment did not envisage Jewish statehood in all or indeed any part of Palestine, a backwater district of the soon-to-be dismembered Ottoman Empire, even though some such prospect was in the fullness of time anticipated by its proponents, especially Balfour and also the Prime Minister, David Lloyd-George. Supporters of Zionism, like South Africa’s Jan Smuts, believed as early as 1918 that a heterogenous population like Palestine (512,000 Muslims, 66,000 Jews and 61,000 Christians at the time of the Balfour Declaration) required something other than outright autonomy, with its minorities thrown on the mercy of the majority.

Lacking strong legal status in isolation, the Declaration was incorporated into the Sèvres peace treaty with Turkey. The Declaration was also incorporated into the subsequent Mandate for Palestine, adopted in July 1922 by more than 50 member states of the League of Nations, who noted “the historical connection of the Jewish people with Palestine.”

Other British promises and negotiations during the War, including with both the French (Sykes-Picot Agreement) and the Arabs under Sharif Hussein of Mecca (Hussein–McMahon Correspondence) were not incompatible with the Balfour Declaration – there was no ‘twice-promised land’ – but the convoluted, simultaneous transactions with both, a growing sense of the difficulties Zionism posed British strategists and administrators, coupled with an imperfect grasp of their own commitments, resulted in a short space of time in the crystallization of a new orthodoxy.

According to this version, Britain had short-changed the Arabs, in particular, Faisal, titular head of T.E. Lawrence (Laurence of Arabia)’s Arab Revolt, by twice promising Palestine in incompatible commitments to both Arabs and Jews; the Sykes-Picot Agreement was a further imperialist fraud on the Arab peoples; and the Balfour Declaration became a negligent, war-time slip of the pen. The British historian Arnold Toynbee first enunciated this version shortly after the War, based on an incomplete and uncritical reading of Foreign Office papers; Lawrence himself gave expression to the ‘betrayal’ component is his book, The Seven Pillars of Wisdom; and the leading publicist of Arab nationalism, George Antonius, was later to give it classical formulation in his apologia, The Arab Awakening. These were to exert in combination a profound influence on officialdom and indeed the pubic imagination and in fact, still do to this day.

The British retreat from the Balfour Declaration was a long and protracted affair and ultimately put Britain and the nascent Jewish state on a violent collision course. This created a vast reservoir of Jewish disaffection. It also gave rise to the mordant joke, once popular among British Jews familiar with the wording of Lord Balfour’s promissory note, that it should have been reworked so as to foreshorten the first sentence: “His Majesty's government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done.” But a good deal was done – and undone.

The British–Jewish collision only passed with the United Nations decision to partition Palestine in November 1947, Britain’s termination of the Mandate in May 1948 and the first Arab-Israeli war that followed the next day. But the Balfour Declaration had sufficed: Zionism had the political capital on which to operate and eventually succeed. Whatever the vicissitudes, the idealism of Balfour ensured a new departure in the long chronicle of Jewish history.