A Primer on America’s Forgotten "Nasty Little War": An Interview with Gregg Jones

In school, most of us learned a couple of facts about America’s evolving imperial ambitions and the Spanish-American War of 1898: the sinking of the battleship Maine in Cuba, the Roughrider charge up San Juan Hill led by Teddy Roosevelt, and Commodore George Dewey’s sinking of the Spanish fleet in Manila Bay. But the ensuing, bloody Philippine-American War of 1899 to 1902 is usually neglected in most standard history courses.

Within months of the victory over Spain, the American “liberation” of the Filipino population from Spanish colonial despotism became an American war against the Filipino independence movement and for conquest of the islands. After suffering overwhelming defeats in conventional battles, the Filipino revolutionaries adopted guerilla warfare tactics, and the U.S. forces responded with brutality. In what General Frederick Funston labeled a “nasty little war” as soldiers randomly fired into villages, burned homes and crops, summarily executed perceived enemies, tortured combatants and civilians with techniques such as a form of water boarding, and committed other atrocities.

More than four thousand U.S. troops died in the Philippines war, whereas fewer than four hundred Americans died in the Spanish-American War -- “a splendid little war,” according to Secretary of State John Hay.

Filipino losses can only be estimated, with some sources reporting more than 20,000 Filipino combatants killed and more than 200,000 Filipino civilians dead from violence, starvation or disease. The war presaged future controversial American wars in Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan.

In Honor in the Dust: Theodore Roosevelt, War in the Philippines, and the Rise and Fall of America’s Imperial Dream, author Gregg Jones recovers the history of the neglected conflict in the Philippines. Based on extensive research, the former Manila-based correspondent details the war from the expansionist policies of the United States and the push back of the Anti-Imperialist League, to the complex military actions against guerilla forces and the reaction of U.S. domestic leaders and citizens.

The history Mr. Jones shares is framed by the acts of one overarching figure: Theodore Roosevelt, from his early saber rattling as Assistant Secretary of the Navy when he pushed for war with Spain, to his heroic charge up San Juan Hill, to his fiery arguments for U.S. expansion and empire as a vice-presidential candidate in 1900, to his presidential leadership as the U.S. military actions bogged down in the Philippines and reports of American atrocities filled newspapers.

Mr. Jones’s book has been praised for his lively writing, balanced account, and extensive documentary research on the history of this forgotten war. Adam Hochschild, author of King Leopold's Ghost, commented: “America's brutal war of conquest in the Philippines is amazingly little-known, largely ignored in our schoolbooks and history museums. Yet its imperial hubris and its torture scandal eerily foreshadow events of the last decade. In his much-needed, highly readable book on this forgotten war, Gregg Jones has written both a compelling page-turner and a work of careful scholarship.” And Candice Millard wrote in The New York Times Sunday Book Review: “Fascinating....In the end, Honor in the Dust is less about the freedom of the Philippines than the soul of the United States. This is the story of what happened when a powerful young country and its zealous young president were forced to face the high cost of their ambitions."

Gregg Jones is also the author of Red Revolution: Inside the Philippine Guerilla Movement. He is a former Pulitzer-finalist investigative reporter and foreign correspondent, and has worked as a staff writer for the Los Angeles Times, Dallas Morning News and Atlanta Journal-Constitution. His writing has also appeared in the Washington Post and Boston Globe, as well as the British Guardian and Observer newspapers. He is currently working on a book about the Vietnam War battle of Khe Sanh.

Mr. Jones talked about his new book and his research by telephone from his office in Texas.

Robin Lindley: What inspired you to write this history of the United States conquest of the Philippines?

Gregg Jones: It was a story that I had lived with a long time. I had gone to the Philippines in 1984. I was 25-year-old newspaper reporter in Atlanta. I had grown up loving history and wanted to go out into the world and write about history as it was being made in some distant place.

I wound up going to the Philippines about eighteen years into the rule of Ferdinand Marcos. Marcos was on the downside of his increasingly dictatorial rule. After covering the fall of Marcos in 1986, I began working on a book about the communist revolutionary movement in the Philippines. They were a major force at the time and were very anti-American and always talking about imperialism.

As I researched that book, Red Revolution, I read about the roots of American involvement in the Philippines. I wanted to understand the history of how we got there and what the modern communist movement in the Philippines claimed were examples of U.S. imperialism.

I was struck by the fact that I was someone who read a lot of history, but did not know about this chapter in our history. I knew about the Spanish-American War: the sinking of the Maine, Roosevelt’s charge up San Juan Hill, and Dewey’s victory at Manila Bay. But I knew nothing of the events that came afterwards, an important missing chapter in our history. I thought that it would make a great book, but I was busy with my newspaper career. I came back to the States in the early nineties, and went back to Asia again in 1997.

In the fall of 2001, I covered the beginning of the war Afghanistan. I went to Pakistan the week after 9/11, and into Afghanistan right after the fall of Kabul. I made two trips to Afghanistan, each about three or four weeks.

When I got back to the States in 2002, I was struck by the emerging debate over the War on Terror, and then the invasion of Iraq followed. The controversy over water boarding took me back to the intense debate that Americans had over the Philippines and the use of torture there more than a hundred years earlier, and I knew it was time to get moving on this idea.

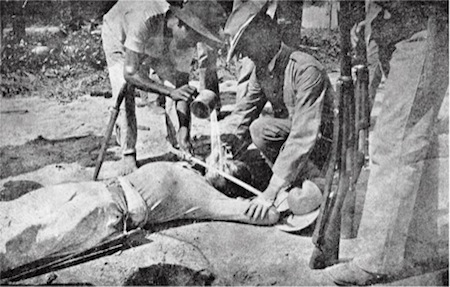

American troops giving Filipino insurgents the "water cure."

I think many of us share your experience that we learned only of the sinking of the Maine and San Juan Hill when we read in school of the Spanish-American War, but we did not learn of the Philippine theater of that war. Wasn’t the American military engagement in the Philippines very brief with few casualties?

Exactly. The first action in the Philippines happened when the U.S. Army was preparing for the invasion of Cuba. There was a great mobilization to throw the Spaniards out there. In the meantime, the Asiatic Squadron of the U.S. Fleet was under the command of Commodore George Dewey. He had been put in that position through the efforts of Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt.

Dewey had been in Asia since late 1897. He was based in Japan, but in the aftermath of the sinking of the Maine, he moved to Hong Kong, anticipating a war with Spain, and Hong Kong was much closer to the [Spanish-ruled] Philippines.

Dewey steamed from Hong Kong to the Philippines in April 1898 after war was declared, and he destroyed the antiquated Spanish fleet in Manila Bay. That was the first blow the United States struck against Spain and Dewey became an overnight hero. It was incredible at the time with people naming babies after Dewey and this outpouring of adulation, which Dewey milked quite a bit.

Meanwhile, on the ground, the Spanish were fighting an indigenous revolutionary movement, just as they were in Cuba. The Filipinos launched a revolution in 1896, and that was preempted by the Spanish government with a peace agreement that sent the Filipino revolutionary leaders into exile.

The head of the Filipino independence movement, Emilio Aguinaldo, was in Hong Kong with about 25 of his commanders. The U.S. had made contact with Aguinaldo and his men in the months prior to the start of the war with Spain. They tried to persuade Aguinaldo to go back and again wage war against the Spaniards, in league with the Americans.

In the weeks after his victory at Manila Bay, Dewey arranged for Aguinaldo to be transported back to the Philippines on an American ship with his other senior commanders. Their meeting on Dewey’s flagship Olympia was a pivotal moment. There are conflicting accounts of what was said. Aguinaldo said he received promises of Philippines independence if the Filipinos would help the Americans beat the Spaniards. Dewey denied that.

We know that Dewey sent Aguinaldo ashore with weapons and Aguinaldo fought the Spaniards quite effectively. By the time the U.S. Expeditionary Force arrived in the Philippines later in the summer, the Filipinos had succeeded in pushing the Spaniards back to the walled city in Manila. The Filipinos had besieged the city when the American ground troops came ashore. Much of the heavy lifting the Americans thought they had would have to do had been done.

Unbeknownst to Aguinaldo and his commanders, the Americans had begun secret negotiations with the Spanish commander of Manila. He agreed to a sham battle to save face.

In August, the sham battle of Manila was staged. The Filipinos were kept out of the city at gunpoint and they nearly came to blows with American troops. The Filipinos were outside the city and the Stars and Stripes went up over Manila. At that point, the Americans and Filipinos were on a collision course.

So the Americans turned on their Filipino allies after the Spanish-American War in the Philippines.

It was a shock to Aguinaldo and his commanders, who had very idealistic notions of America and our own fight for independence. They knew the history of America. And President McKinley had declared that the U.S. did not go to the Philippines with territorial ambitions. U.S. emissaries had told the Filipino revolutionary leaders that they were there to liberate the Filipinos from oppressive Spanish rule. It was a shock and great disappointment for Filipinos when it became clear that the Americans were there in force and intended to stay.

It took several months before the tensions finally erupted. There were a number of incidents in the fall of 1898 on the ground around Manila leading up to the outbreak of hostilities on February 4, 1899.

Meanwhile, there was great debate in America on what was known as “the Philippines Question.” What was America to do with these islands it now possessed as the result of the Spanish-American War? Peace negotiations began in Paris in the fall of 1898 between the United States and Spain.

The debate on what to do with these islands reached a peak in September and October 1898 in America. It became very much entwined in domestic politics. Theodore Roosevelt came back from Cuba a hero and was running for governor of New York in the election of November 1898. He was delivering speeches saying that America had a responsibility to keep these possessions, to embrace world power and our responsibilities as a colonial power. Rising Republican politicians like Albert Beveridge of Indiana were delivering powerful speeches, arguing that the United States should retain the Philippines.

McKinley, who was not a decisive character but was an astute politician, did a listening tour across the Midwest -- in Illinois, Iowa, Missouri, Nebraska, and Kansas -- and it became evident that there was popular support for the idea of the United States becoming an expansionist power and keeping the Philippines. McKinley told his negotiators to demand all the Philippine islands from Spain, which the United States ultimately bought for 20 million dollars. The deal was done without any participation by the Filipinos themselves.

The U.S. Senate was prepared to vote on the treaty that would annex the Philippines when fighting broke out between U.S. and Filipino forces in February 1899, and two days later the Senate approved annexation of the islands with one vote to spare.

And before that, hadn’t the Filipinos already set up a constitutional government with Emilio Aguinaldo as president?

Yes. That happened just a matter of weeks after Commodore Dewey destroyed the Spanish fleet. On June 12, 1898, Aguinaldo declared an independent Philippines republic. He invited Dewey to the celebration, and Dewey put off Aguinaldo, saying he had important duties because it was “mail day” for the fleet, so he couldn’t attend. From June of 1898, there was a functioning republic of the Philippines.

And you describe the savage war that ensued -- and presaged our conflicts in Vietnam and then in Iraq and Afghanistan. You note the atrocities on both sides, and the American use of torture, burning of villages, killing of civilians, and concentration camps.

Yes. One of the American heroes of the war, Frederick Funston, described it as a “nasty little war” as Filipinos abandoned conventional war and began waging a guerilla war against the Americans. That was quite accurate. Guerilla wars are nasty wars.

Filipino dead.

The Filipinos resorted to ambushes, assassinations, raids, and that sort of thing. And the responses became increasingly harsh. Initially, an ambush or assassination might be met by burning a house or two, and then it became burning a village destruction of crops. Food deprivation became a weapon early on in the war.

Then there was torture of suspected guerillas and sympathizers. The Americans adopted a torture technique that the Spanish had imported into the Philippines and dated back to the Spanish Inquisition. It was torture by water, and became known in the Philippines as “the water cure,” and it was the antecedent to water boarding. It was widely used, as we know from the accounts of soldiers. There are at least three photographs that exist (and are included in the book) showing U.S. troops actually using it or simulating interrogations using the water cure. This later came out in a number of courts martial, that this was widely used, and several units were known for its use.

Soldiers from the 35th Volunteer Infantry Regiment waterboarding a Filipino prisoner.

How much did the American public know about how the war was conducted by U.S. forces?

Soldiers were writing home, describing their interactions with Filipinos from the first weeks in the Philippines. When war broke out, letters from soldiers described the destruction of villages and opening fire on villages. Some of these letters appeared in newspapers.

Keep in mind that there was dismay in the minds of many Americans that this war, that was supposed to liberate the Filipinos, had resulted in U.S. troops in combat with the very people they had been sent to liberate. In fact, America’s diplomat on the ground in Manila sent back cables and reports stating that the United States would be welcomed as a liberator and there would be an embrace of American colonial rule there.

It came as a shock to many Americans that we were not welcomed as liberators, and that we were actually killing Filipinos. And it went beyond that: acts such as burning villages, burning crops, and using the water cure and other interrogation methods against the Filipinos. This became public knowledge very early.

The expansionist movement that supported the war and the annexation of the Philippines was dominated by Republicans such as Theodore Roosevelt, Henry Cabot Lodge, and some strategic thinkers. But there were also some Republicans who were vehemently opposed to the war: men like Andrew Carnegie, the great industrialist; former Senator Carl Schurz who had been a friend of Lincoln; and Senator George Frisbie Hoar of Massachusetts, who adamantly opposed the war.

These opponents of the war brought attention to the letters and reports [of atrocities] from the Philippines. They argued it was not only against America’s principles to annex the islands and violate the principle of “consent of the governed,” which we held dear, but also we were doing it in a way that violated our commitment to liberty, justice and rule of law.

The issue played out in the presidential election of 1900 with many of the same arguments that we saw with Iraq and Afghanistan. Opponents of the war seized on acts of torture and other acts of the American military, while supporters of the war pointed to the opponents and said they were traitors and they were endangering U.S. troops by encouraging Filipino revolutionaries. There was an acrimonious back and forth.

Was the war in the Philippines a prominent issue in the 1900 election?

Through the summer of 1900, as the Democrats and Republicans held their nominating conventions, both parties were convinced that the Philippines would be the paramount issue in the fall campaign, and they both said this.

The Republican incumbent was William McKinley and he chose as his running mate Theodore Roosevelt, an ardent expansionist who supported the war and said the United States had to stand firm and embrace world power and colonial rule.

On the other hand, the Democratic candidate was the populist William Jennings Bryan, who was popular with rural Americans. Bryan was not staunchly committed to what was known at the time as “the anti-imperialist cause.” Bryan was more interested in domestic economic issues, and the so-called “Free Silver Issue” was his pet cause. But Bryan was persuaded that he needed to make the Philippines the paramount issue and that the election of 1900 would be a referendum on the war.

Initially, in August and September, Bryan delivered stinging speeches attacking the Republicans and McKinley on the policy of annexing the Philippines and waging this war against Philippine independence. But then Bryan wearied of the issue and abandoned it. As the campaign went on, the Democrats all but stopped talking about the Philippines. Bryan had initially attracted the support of the anti-imperialist movement, which included a lot of Republicans who had broken with the party over this issue, and Independents, but as he abandoned the issue of expansion this support waned.

And Mark Twain was a very vocal anti-imperialist.

Mark Twain arrived very late in the campaign, in October. He had been in Europe for an extended period. He returned and spoke stridently against America’s war in the Philippines, but he was too late. Theodore Roosevelt had seized control of the campaign. He had delivered 500 speeches from one end of the country to the other. He was a great campaigner with a lot of energy. The Republicans successfully painted the Democrats as fiscally irresponsible socialists and as a party that would plunge the United States into economic chaos at home and would bring shame on America by retreating overseas.

It’s hard to say to what extent people voted in November 1900 as a referendum on the war. Certainly it was a factor. I think domestic economic issues mattered more to most voters than the war in the Philippines. Certainly, once the Republicans won a landslide victory, some Republicans said it was a referendum on the war. Case closed.

The final phase of the war then began with a stepped up military offensive and very severe measures aimed at stamping out resistance.

Can you talk about the final stage of the war after the election of 1900?

The election was clearly a turning point. The Filipino revolutionaries had deluded themselves into thinking that the Democrats were going to win the election and the war would end and they’d gain independence.

The Filipinos were following U.S. domestic politics closely. They timed military offensives and guerilla attacks through the fall campaign, so you had some of the bloodiest incidents of the war in September and October in the run-up to the U.S. election. Through the ranks, they had been told that only if they fought through the election then everything would change. When that didn’t happen, it was devastating for the revolutionary movement in the Philippines.

You had an increase in surrenders in the months following the election. The supreme commander in the Philippines then was General Arthur MacArthur, the father of Douglas MacArthur. He rolled out a severe crackdown on the Filipinos that targeted not only the guerillas in the field but also the support network in the cities and villages. Many leaders were exiled to Guam. In the countryside there were blockades and suspension of trade in areas where guerillas were active. The guerillas and the population were starved into submission in several areas.

Then, by March 1901, the swashbuckling General Frederick Funston -- the leader of Kansas volunteers who had been awarded the Medal of Honor in the early months of the war and became a great hero of the war to Americans -- led an expedition to the far corners of northeastern Luzon. From captured intelligence, Funston had learned of the village where Emilio Aguinaldo, the Filipino independence leader, had his headquarters. Funston and a handful of his trusted men posed as prisoners and Filipinos who were loyal to the American cause posed as reinforcements that Aguinaldo had requested. This expedition arrived at Aguinaldo’s headquarters and took Aguinaldo prisoner.

Aguinaldo’s capture was a crushing blow to the revolutionary movement. Aguinaldo was brought to Manila and treated with great equanimity by General MacArthur, and Aguinaldo called on his commanders in the field to surrender.

By the fall, there were only two major commanders in the field: one in the Batangas province of Luzon and one on the wild central island of Samar, the third largest island in the Philippines.

On July 4, 1901, William Howard Taft was inaugurated as the first civilian governor of the Philippines. The transition from military to civilian ruled gathered steam into the fall.

In September, President McKinley was assassinated. About two weeks after Theodore Roosevelt became president, an American outpost on Samar was overrun by Filipino guerillas and civilians. It was called the Balangiga massacre. It was shocking, and Roosevelt ordered his commanders and Secretary of War to end resistance. An offensive was launched on Samar and very harsh measures were implemented.

At the same time, U.S. forces went on the offensive in Batangas province on Luzon. Batangas became well known for the concentration of civilians in camps. So you had these reconcentrados that were strongly criticized by the Americans when used by the Spaniards against the revolutionaries in Cuba. These tactics, as harsh as they were, were also quite effective, and the guerillas were killed or starved into submission. The surrender of the last major commanders both occurred during the early months of 1902.

At the time of these final campaigns, word of what was happening reached Americans and there was renewed interest in how the war was being waged. Roosevelt was pressured by Republican Senator Hoar, a war opponent, to hold hearings in the Senate. The hearings were held under the auspices of Roosevelt’s friend, the junior senator of Massachusetts, Henry Cabot Lodge, by his committee on the Philippines.

In the course of the hearings, some of the unsavory actions came to light and became embarrassing for the Roosevelt administration. Roosevelt and his Secretary of War, the respected Wall Street lawyer Elihu Root, ordered the commanders on the ground to investigate how widespread these problems were, and more issues came to light. There were a series of courts martial that involved famous American officers who were accused of torturing and summarily executing Filipinos.

Within a matter of weeks, Roosevelt got fed up with all of the criticism and launched a counteroffensive. Henry Cabot Lodge delivered a defense of the administration on the Senate floor.

On Memorial Day, in May 1902, Roosevelt went to Arlington National Cemetery and delivered his most extensive public comments on the war crimes scandal that engulfed the administration and the U.S. military. On the one hand, Roosevelt conceded that some undesirable actions occurred, but he minimized the extent of these incidents and blamed Filipino provocations for the acts of American soldiers. While he pledged action, he couldn’t resist striking back at his opponents. Roosevelt launched into a diatribe about how the actions of American troops in the Philippines didn’t compare to the lynchings and other terrible acts committed by Southern Democrats. So with this mea culpa, Roosevelt tried to turn this political blow around on his enemies, and that marked the turning point.

The public tired of the war crimes scandal quickly. It was so discomfiting and disturbing that people were eager to move on and forget about the Philippines.

Congress recessed in late June 1902, and a couple days before July 4, Roosevelt summarily declared that the war in the Philippines was over.

There continued to be some sporadic guerilla activity on various islands. The Muslim population was largely confined to the southern island of Mindanao and small chains of islands off the southwest coast of Mindanao, and guerrilla attacks and very severe U.S. responses continued there for years.

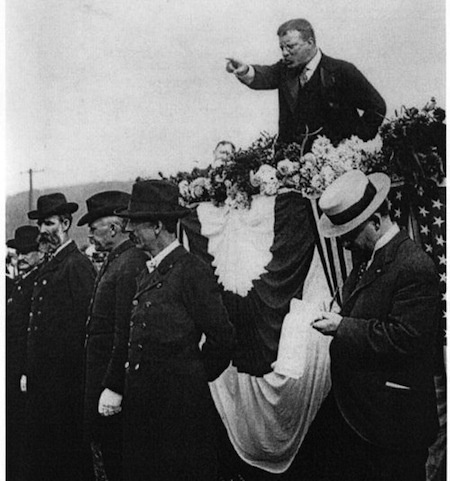

Theodore Roosevelt's Memorial Day speech in 1902.

Theodore Roosevelt's Memorial Day speech in 1902.

This war is virtually missing from our history. You note that Theodore Roosevelt also ignored the Philippines and the war in his memoirs.

Exactly. The national amnesia that engulfed that chapter in our history, Roosevelt very much contributed to it. When it came to the Philippines and the war crimes scandal, Roosevelt did not dwell on it.

This was a painful episode for America and for Roosevelt. It’s fascinating, given all that’s written about Roosevelt and all we know about him, that this is an under covered episode.

It’s understandable, given all of the achievements that followed, that this episode in the first year of Roosevelt’s presidency doesn’t get much examination by historians, but it was significant and ultimately had an impact on how Roosevelt behaved as president. In the following year, 1903, the Panamanian revolution broke out against Colombia. Roosevelt encouraged the revolution so [the U.S.] could complete a canal across the isthmus that the French had abandoned. But Roosevelt did not respond with massive force, as the U.S. had done in the Philippines. He did so with U.S. ships and a small number of troops, so [he used] the threat of force.

A couple of years later, when Cuba was in turmoil, the expansionist Albert Beveridge encouraged Roosevelt to annex Cuba. Roosevelt adamantly refused to do so and he dismissed Beveridge as extreme in his advocacy for annexation of Cuba. That was fascinating because Beveridge was acting and speaking as Roosevelt had about annexation of the Philippines a few years earlier.

The political mood had changed in America, and Americans didn’t have the stomach to become an imperial power and to do all that was required to conquer foreign lands.

It’s striking that this history of the war in the Philippines was purged from the national memory within a few years.

It’s remarkable. I don’t remember reading a word about it in my history books growing up.

The Philippine-American War was expunged from our history. In the 1960s, the war in Vietnam unleashed a rediscovery of the war in the Philippines, but that faded after a few years.

With the invasion of Iraq and the war in Afghanistan, debates over the use of U.S. power and our tactics in the pursuit of our aims abroad were again front and center in the national discussion.

I wanted to recover this forgotten chapter in our history because I think we need to know these stories and these debates from our past. We need to make more informed decisions as individual citizens and as a nation.