Tenemos un Papa!

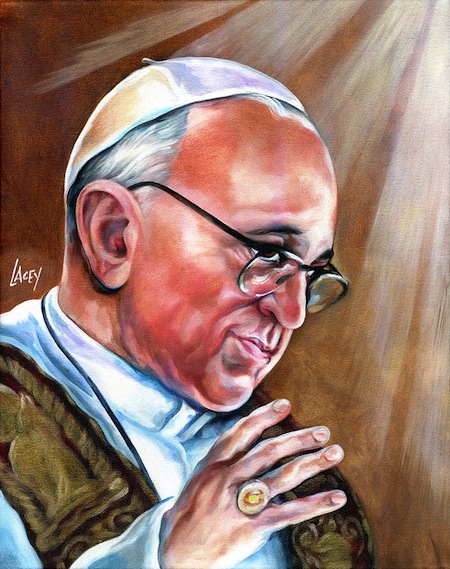

Pope Francis. Painting by Dan Lacey via Flickr.

At 8:12 p.m. on Wednesday, March 13, Cardinal Jean-Louis Tauran announced from the famed loggia of St. Peter’s Basilica “Habemus Papem,” “We have a pope.” Within minutes, as the world's 1.2 billion Catholics and curious onlookers worldwide processed the announcement that Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio of Buenos Aires had been elected the 266th pope, Latin Americans and U.S. Latinos exclaimed “Tenemos un Papa,” “We have a pope!” Or, as the Huffington Post announced, “The Holy Sí! Argentine Pope.” What does it mean to have a Latin American pope?

In the days leading up to the conclave, speculation abounded as to the concerns and motives of the College of Cardinals. Reports in the U.S. press characterized the conclave as divided between Romans and Reformers. Romans, Vatican insiders, concerned with maintaining the status quo in the curia, where much of the administrative work of the Church is done, were perceived to be lining up support for Cardinal Odilo Pedro Scherer, the archbishop of São Paolo. Scherer was portrayed as an administrator with ties to the curia, and would have been an unprecedented choice, as he would have been the first pope from outside Europe in over a thousand years. The Reformers sought change in the curia, perceived to be corrupt and closed to outsiders – even the cardinals and bishops from outside the Roman inner circle. The Reformers appeared to be backing Cardinal Angelo Scola, the archbishop of Milan. These selections countered the geography of conventional wisdom with commitments to stasis, in the Brazilian, or change, in the Italian. This dichotomy certainly represented U.S. perspectives on the administration of the Roman Catholic Church. Bergoglio was not even considered a contender under this framework.

Since Benedict XVI announced his resignation on February 11, Catholic attitudes and concerns have been carefully scrutinized. As we learned during the most recent U.S. elections, U.S. Catholics and their leadership are not necessarily aligned in their thinking on pressing social issues, such as the use of contraception, the ordination of women, and the resolution of priest child sex abuse cases in the United States. It should be no surprise, then, that the College of Cardinals did not embrace the concerns of U.S. Catholics, let alone the broader U.S. public in choosing Bergoglio.

Latin American and Latino Catholics initially celebrated Pope Francis, but there has been some reeling back of that emotion in subsequent days. The selection is not without controversy, like the Church itself, in Latin America. Francis is representative not of the concerns of Catholics in the Global North; rather, he embodies the Church in the Global South in the twentieth century, where alliances between high-ranking clergy and oppressive regimes often legitimized brutal treatment of those working toward human rights, redistribution of wealth, and democracy. Bergoglio and many senior prelates were wary of theologies of liberation, which they perceived as being tainted with Marxism. Concerns have been raised about Begoglio’s role in Argentina’s “Dirty War” in the 1970s, in which tens of thousands were tortured and killed for resisting the military dictatorship. As leader of the Argentine Conference of Bishops in the 2000s, Bergoglio did not apologize or otherwise acknowledge the actions of a priest convicted of atrocities during the Dirty War. These national scars, which still divide Argentina and other Latin American countries, continue to shape the Roman Catholic Church in the Global South. Anglican Archbishop Desmond Tutu, in the post-apartheid era, argued that reconciliation cannot be achieved without knowing the truth. One hopes for as much for Argentina and its church as it continues to recover from the national ravages of the Dirty War.

Still, Pope Francis is a revolutionary choice in spite of his theological conservatism. Electing a pope from the Global South represents a significant change for the leadership of the Church, not only because Francis is the first pope from outside of Europe since Syrian Pope Gregory, elected in 741. The body that chose Francis is heavy in its representation from the Global North, and is the legacy of an ecclesiastical structure that is likely unsustainable in the twenty-first century. Whereas 42 percent of Catholics are in Latin America, only 16 percent of parishes, and 17 percent of priests are in that part of the world. Africa likewise lags behind in parishes and priests for a Catholic population of its size. In Europe and North America, in contrast, the shrinking Catholic population is overrepresented in terms of parishes, priests, and especially bishops and cardinals. It remains to be seen if Pope Francis has a solution to these structural challenges facing the Church.

Pope Francis is also a remarkable choice for more historical reasons. He is the first Jesuit pope. The Society of Jesus, long known for its independence and resistance to the trappings of power and prestige, has historically focused more on missionary work and, more recently, academic institutions. Jesuits are also known for seeing God in all things and for living simply. As archbishop, Bergoglio lived in an apartment rather than a courtly palace and rode the bus to work rather than being chauffeured on a daily basis. He has shown the same inclination as pope, joining the cardinals on the bus back to their temporary residence after his elevation. This commitment to simplicity is also shown in the adoption of Francis, after St. Francis of Assisi, as his papal name. Francis is the first since Pope Romanus in 897 to take a new name (not including John Paul, who combined names used twenty-three and six times prior, respectively). Pope Francis recounted to journalists a few of his thoughts from the conclave. After he achieved the requisite number of votes, his Brazilian friend, Cardinal Claudio Hummes told him “Don’t forget the poor.” He thought to himself that St. Francis represented goodness, peace, and creation, values that are often lost in the modern world. Pope Francis seems to represent the simplicity and humility of St. Francis, with not only the name, but by asking his first papal audience to pray with him and for him before offering the traditional blessing by the new pope.

Whether or not they support Pope Francis, Latin American and U.S. Latino Catholics and others can see his election as an opening up of the church. Theologian Timothy Matovina noted recently that for decades the Catholic Church in the United States has told Latino parishioners, “you are welcome here,” suggesting they are guests in the church. Latinos, in fact, are the demographic future of the Roman Catholic Church in the United States. The cardinal electors have indeed affirmed to Roman Catholics in Latin America and the Global South, more broadly: this is your Church, too. The cardinals likely hoped this selection, from the continent with the most Catholics, would bring Latin Americans and others who have wandered from the faith back to a Roman Catholic Church that sees in them its future.

Related Links