Why We Still Need the Voting Rights Act

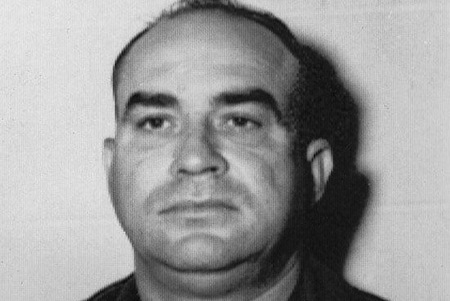

Mug shot of Olen Burrage in 1964.

The expected gutting of the Voting Rights Act (VRA) by the Supreme Court in Shelby County v. Holder has captured many headlines of late, and with good reason. Less than fifty years removed from the VRA’s passage and in the face of mounting state-by-state efforts to restrict the franchise, the Roberts Court appears poised to undo one of the civil rights movement’s hallmark achievements. As an array of voting rights advocates and legal experts have demonstrated, such a decision would make it substantially more costly and difficult for citizens and organizations to challenge voting restrictions that are discriminatory in intent or effect.

At the same time, a deeply relevant case on the Court’s docket, that of Fisher v. University of Texas, has generated somewhat less mainstream scrutiny. Engineered by Edward Blum, a zealous opponent of government support for and protection of civil rights, Fisher challenges the University of Texas’s admissions policy on the grounds that, by considering race as a factor in admissions, it discriminates against white people. Yet for those leading the charge, Blum especially, the ambition is much greater: to eviscerate affirmative action.

The politics of affirmative action aside, from the outset, Fisher as a legal complaint has been a sham. In a March 18 story for ProPublica, Nikole Hannah-Jones sketched out the shaky grounds on which the plaintiffs brought suit. Abigail Fisher was a good-not-great student at her Texas high school. Because of UT’s policy of automatic acceptance for in-state students in the top ten percent of their graduating class, Fisher (who didn’t qualify for automatic acceptance) was competing for just a handful of at-large admission slots. The rejection rate for those remaining slots, numbering fewer than nine hundred, was steeper than Harvard’s. Many minority students with better credentials than Fisher’s were also denied admission. Forty-two of the forty-seven students with worse grades and test scores than her who were offered at-large spots were white. She could easily have easily gone to a different university in the UT system, and transferred into Austin after her first year. Simply put, there isn’t much legal substance to Abigail Fisher’s specific complaint.

The likely problem, of course, is that the conservative justices on the Roberts Court don’t care. For Blum and Fisher, it’s hard to realistically imagine a more auspicious audience. Antonin Scalia long ago abandoned any pretense of considering racism and its consequences as serious legal or social matters, as most recently demonstrated in his flip statement that the VRA’s Section 5 represented the “perpetuation of racial entitlement.” That sort of hostility toward governmental redress of historic racial wrongs is echoed in the records of Justices Alito, Roberts, and Thomas. Justice Kennedy, the lone toss-up in the Shelby County case and most others related to race, hinted at the ruling direction he’s leaning when he remarked, regarding whether or not the VRA was outdated, that “times change.”

Historians’ bread and butter is in the fact that “times change.” Yet they don’t always change that much, or that fast. As Fischer and Shelby County await their respective rulings, on March 15 and some nine hundred miles away from Washington, Olen Burrage died quietly in Meridian, Mississippi. Burrage will be remembered as the man on whose property the bodies of civil rights workers Andrew Goodman, James Chaney, and Michael Schwerner were buried, after they were abducted and murdered during the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee’s 1964 Freedom Summer. Local prosecutors declined to bring charges, and the federal government’s case against Burrage for violating the trio’s civil rights ended in acquittal in 1967. Yet based upon later statements by an FBI agent and fellow Ku Klux Klan member, not to mention the implausibility of his claim that he was unaware that the Klan bulldozed his property in the dead of night to bury the three bodies fifteen feet underground, Burrage was almost assuredly guilty -- of conspiracy, at least -- in the murders.

The quiet passing of Olen Burrage at the age of 82, free to walk this earth for the forty-nine years since the murders, serves as a reminder of our temporal proximity to the brutal racism of our collective past. The legacies of that racism, and those of the far more complex and varied suppressions of African American life and possibility wrought by both private antagonisms and public policies, are what measures like the VRA and affirmative action programs have sought to redress. Beyond racist violence, the inheritances of our shared racial past are legion: crumbling infrastructures of urban communities; wealth inequality that’s worsened over the past half-decade; educational inequality; food insecurity; high mortality rates; and so forth. An honest look at the landscape makes it hard to brook the lameness of the idea, a la Justice Kennedy, that “times change.”

That poor excuse for a judicial opinion isn’t just Kennedy’s cross to bear, though. Rather, it reflects something of the intellectual place that American society has arrived at when it comes to race. In his prize-winning opus From Jim Crow to Civil Rights, legal historian Michael Klarman noted that social and political contexts matter a great deal in judicial decision-making when a judge lacks particularly strong feelings on a case. There are few clearer examples of this than Kennedy, who is far from alone in thinking it may be time to put our racial past behind us. Such is the world that the myth of post-racialism has tried to make. Americans as a whole like to tell themselves that racism and racists are aberrations or relics of a bygone era. But we tell fictions when we do so.

Like it or not, we live in a world of yawning racial inequalities, cultivated by generations of racial proscription and many decades of destructive public policies. Relatedly, it is a world haunted by ghosts: those of Trayvon Martin and Kimani Gray and Hadiya Pendleton, all of whose young lives ended through circumstances stemming from racial antagonism or inequities embedded in their communities. And until just a few days ago, it was literally the world of Olen Burrage, too.

If the Court proceeds to rule against the VRA and for Abigail Fisher, it is not because times have changed. It is, rather, because the justices have chosen to ignore the ways that they haven’t.