Much Ado about Islands

Credit: Wiki Commons.

This article is a condensed version of a longer essay which appeared in JapanFocus.

More than six decades from the San Francisco Treaty that purportedly resolved the Asia-Pacific War and created a system of peace, East Asia in 2013 remains troubled by the question of sovereignty over a group of tiny, uninhabited islands. The governments of Japan, China, and Taiwan all covet and claim sovereignty over the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands.

The islands, known in Japanese as Senkaku and in Chinese as Diaoyu, are little more than rocks in the ocean, but they are rocks on which there is a real prospect of peace and cooperation in the region foundering.

The Long View

While economic integration in East Asia proceeds by leaps and bounds and popular culture flows freely, the region has little sense of shared history, identity or direction and it is still framed by the security architecture of the Cold War. The difficulty is compounded by the process of gradual, but fundamental, shift in the power balance that prevailed throughout the twentieth century. China rises and Japan declines, a phenomenon that may be encapsulated in a single set of statistics. The Japan that as proportion of global GDP was 15 percent in 1990 fell below 10 percent in 2008 and has been projected to fall to 6 percent in 2030 and 3.2 percent in 2060; the China that was 2 percent in 1990 is predicted to reach 25 percent in 2030 and 27.8 percent in 2060. It is that shift in relative weight, perhaps more than anything that disturbs Japan. Islands that in themselves are trivial come to carry heavy symbolic weight.

What are These Islands and What is Their Significance?

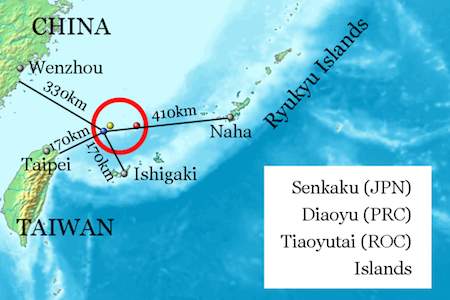

The Senkaku/Diaoyu island group comprises five uninhabited islands, known respectively under their Japanese and Chinese names as Uotsuri/Diaoyudao, Kita Kojima/Bei Xiaodao, Minami Kojima/Nan Xiaodao, Kuba/Huangwei and Taisho/Chiwei. The largest (Uotsuri/Diaoyu; literally “Fish-catch” in Japanese, “Catch-fish” in Chinese) is 4.3 square kilometers and the total area of all five just 6.3 square kilometers. The islands are spread over a wide area of sea, about 27 kilometers separating the core cluster of three islands (Uotsuri, Kita Kojima and Minami Kojima) from Kuba, and about 110 from Taisho. They are located in relatively shallow waters at the edge of the Chinese continental shelf, 330 kilometers east of the China mainland coast, 170 kilometers northeast of Taiwan, and about the same distance north of Yonaguni (or Ishigaki) islands in the Okinawa group, separated from the main Okinawan islands by a deep (maximum 2,940 metres) underwater trench known as the “Okinawa Trough” or in China as the “Sino-Ryukyu Trough.”

In administering the Ryukyus from 1951 to 1972, the U.S. also assumed control of seas that included the Senkakus. However, in the negotiations over Okinawan reversion (1969-1972) it drew a line between the different sectors, transferring to Japan sovereignty over Ryukyu but only administrative control over Senkaku. Sovereignty was left unresolved, in implicit admission that the islands might be subject to competing claims. The United States has held strictly to that position to this day.

Why then, did the U.S. split Senkaku from Ryukyu in 1972? The historians Hara Kimie and Toyoshita Narahiko, among others, attribute the decision to Machiavellian U.S. design. They believe it was explicit and deliberate. According to Hara, the U.S. understood that the islands would function as a “wedge of containment” of China and that a “territorial dispute between Japan and China, especially over islands near Okinawa, would render the U.S. military presence in Okinawa more acceptable to Japan.” According to Toyoshita, the U.S. took a deliberately “vague” (aimai) attitude over territorial boundaries, sowing the seeds or sparks (hidane) of territorial conflict between China and Japan, and thereby ensuring Japan’s long-term dependence on the U.S. and justifying the American base presence. For both, the implication is clear: the Senkaku/Diaoyu problem of today is the consequence of a U.S. policy decision. Though conscious intent is necessarily difficult to prove, their hypothesis certainly offers a plausible explanation for the American shift of position.

The Shelf, 1972-2010

Subsequently, Japan and China paid attention to Senkaku/Diaoyu on two key occasions, in 1972 and 1978. When Japanese prime minister Tanaka Kakuei raised the question to Chinese premier Zhou Enlai in '72, Zhou replied that the matter should be shelved as opening it would complicate and delay the normalization process. Six years later, in Japan to negotiate a Peace and Friendship Treaty, Deng Xiaoping reiterated this “shelving” formula, preferring to leave it to “the next generation” to find sufficient wisdom to resolve it. For roughly forty years a modus vivendi held: though occasional landings by Chinese activists from a Hong Kong base and by Japanese rightists sailing from ports in Okinawa took place, the two governments tacitly cooperated to prevent them.

In two decisive steps, however, in 2010 and 2012, Japan moved to ensure that the shelf would not be put back. In 2010, the Democratic Party of Japan’s government arrested the Chinese captain of a fishing ship in waters off Senkaku, insisting that there was “no room for doubt” that the islands were an integral part of Japanese territory, that there was no territorial dispute or diplomatic issue, and the Chinese vessel was simply in breach of Japanese law (interfering with officials conducting their duties). The fierce Chinese response caused Japan to back down and release the captain without pressing charges, but Japanese resolve hardened and China appears to have concluded that Japan had determined to set aside the “shelving” agreement. Mutual antagonism deepened steadily thereafter.

Abe - “Taking Back”

Abe Shinzo campaigned for the December 2012 lower house election under the overall slogan of “taking back the country.” He pledged not to yield one millimetre of Japan’s “inherent” territory of Senkaku, a matter on which there was no dispute, no room for discussion or negotiation. He wrote:

“What is called for in the Senkaku vicinity is not negotiation but physical force incapable of being misunderstood.”

The intransigent language of Japan in 2012 and 2013 was reminiscent of 1937, when Japan’s then leader, Konoe Fumimaro, ruled out negotiations with China’s Chiang Kai-shek in the fateful months leading to full-scale war with China, and when the national media was similarly self-righteous and dismissive of China’s “unreasonableness” and “provocation.” To China it looked as though Japan was actively collaborating in construction of a militarized Maritime Great Wall of China to block its access to the Pacific Ocean. In April 2013 Diaoyu was for the first time declared a “core interest,” and in May the People’s Daily added that the status of Okinawa itself had to be negotiated.

China’s claim

The Chinese claim (mainland and Taiwan alike) to Diaoyu rests on history (the records of the Ming and Qing dynasties) and geography (the continental shelf and the deep gulf that sets the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands apart from the Ryukyu island chain). For both, the islands are an integral part of Taiwan’s territory and the fact that they were appropriated by Japan as part of the violent processes of the Sino-Japanese War, and should therefore have been returned to China under the Potsdam Agreement, is plain.

In general, China and Taiwan are united in their stance on Senkaku/Diaoyu matters, but it ought to be noted that a Japan-Taiwan fisheries agreement was concluded in 2013 (after seventeen years of talks) under which Taiwanese fishermen would have right to fish in certain specified waters adjacent to Senkaku/Diaoyu, if not in near coastal waters. It may be seen as a smart Japanese diplomatic gesture to split Beijing and Taipei, and thus to ease the pressure from hostile confrontation on all its frontiers. It presumably mans that the Taiwan coastguard will no longer confront Japanese forces with hostile intent. The deal made no reference to territorial issues but Beijing objected, and whether it will hold remains to be seen.

Kyoto University’s Inoue Kiyoshi made the point forty years ago that “even though the [Senkaku] islands were not wrested from China under a treaty, they were grabbed from it by stealth, without treaty or negotiations, taking advantage of victory in war.” It is a judgement confirmed in 2012 from the opposite end of the ideological spectrum by The Economist, which wrote: “Whatever the legality of Japan’s claim to the islands, its roots lie in brutal empire-building.”

What Is To Be Done?

Where the Japanese case for exclusive entitlement to the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands is strong on a strict reading of international law, China’s is strong on grounds of history and geography. Its insistence that the frame for thinking of the problem include not just an antiseptic “international law” but the record of colonialism, imperialism, and war also has a moral quality.

There are no tribunals to adjudicate on such conflicting claims and, despite the assumption that there has to be a “right” answer, international law is no set of abstract and transcendent principles but an evolving expression of global power relations, reflecting at any one time the interests of dominant global powers. None of the state parties (Japan, China, Taiwan) is likely to submit to any formula that holds the possibility of a zero outcome. So, even though there are no residents of these islands with rights to be protected and in that sense resolution should not be so difficult, and despite the large economic interests shared by China and Japan, recourse to international law arbitration is highly unlikely.