Five Myths about the “Surge” of Central American Immigrant Minors

Both the President and Senate Republicans have recently weighed in on what to do about the “surge” in undocumented minors arriving at the US border. Many of these undocumented youth come from the northern countries of Central America: Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras. Embedded in most arguments about what ought to be done are assertions about what prompted these minors to set out in the first place and what will become of them if they stay. But many of these assumptions miss the mark and the truth is a lot more complicated than the sloganeering that characterizes much of the debate.

Myth #1: The increase in migrating minors came about as a result of the rise of gang violence in Central America.

Gang violence in Central America is real and it has touched the lives of far too many Central American youth and families. But the gangs have been a major feature of urban life since at least the late 1990s and there is little evidence to argue that gangs have increased in strength, size, or activity during the past three years. Meanwhile, the increase in migration of minors has been stratospheric. Undeniably, some of the youth heading north are escaping gang violence or threats from the gangs, but even the UN’s special report Children on the Run found, after conducting interviews with a scientific sample of detained youth, that just under a third of the youth mentioned the gangs as a factor contributing to their decision to leave. Most of the youth citing gangs were from El Salvador and Honduras.

Myth #2: Violence is spiraling out of control throughout Central America.

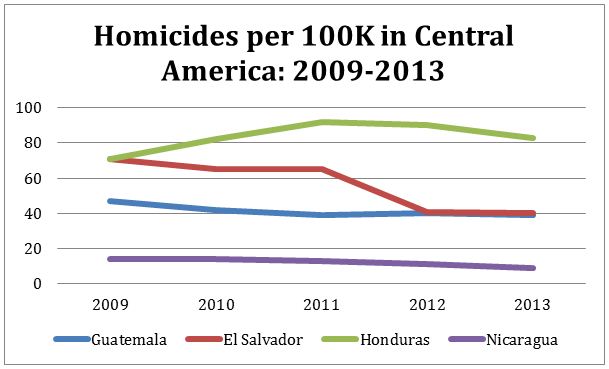

Although they share a number of important characteristics, the governments of Central America have taken different paths in how to relate to gangs, drugs, and violent crime. These divergent policies have contributed to very distinct outcomes. Notably, Nicaragua, which never took an “iron fist” approach to the gangs, has a far lower homicide rate and lower gang membership than its neighbors to the north. But even Guatemala, which has been well-known for homicidal violence ever since the state-sponsored violence of the 1980s, has shown improvement in its violent crime rate. Homicides have generally declined in recent years, probably as a partial result of Guatemala’s efforts to improve its justice system. As the chart below illustrates, Honduras has more than double the homicidal violence of its neighbors:

Myth #3: Coyotes (sometimes called “human traffickers”) are “tricking” children into migrating by telling them that they will receive citizenship upon arrival in the United States.

This myth reveals the utterly low regard in which many North Americans hold the intelligence of Central Americans. Oscar Martinez, an award-winning investigative journalist from El Salvador, recently published a fascinating account of his interview with a Salvadoran coyote who has been guiding his compatriots to El Norte since the 1970s. (Oscar knows about migrating minors — he has written a celebrated book about his trips across Mexico in the company of Central American migrants.) Among other myths effectively debunked in that interview is the notion that Central Americans hold wildly optimistic views about Border Patrol and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). In fact, most Central American youth and their relatives living in the United States are well aware that in all likelihood, they will, at best, become undocumented immigrants. But better to be close to family than suffer years of hardship while separated from parents, many of whom cannot travel “back” to their country of origin because of their own undocumented status. Of course, some of these youth are also escaping violence and the threat of violence as well as economic hardship and the crushing humiliation of living in generational poverty in some of the most unequal societies in the hemisphere. Thus, there are multiple factors at play when Central American youth (and their parents) consider whether or not to pay the US$7,000 charged by most coyotes for “guidance” across Mexico and over the US border. But few arrive under the illusion that they will attain legal status any time soon.

Myth #4: Central American youth who manage to stay in the United States as undocumented persons are likely to become part of a permanent underclass who represent a perpetual drain on the US economy.

Myth #4: Central American youth who manage to stay in the United States as undocumented persons are likely to become part of a permanent underclass who represent a perpetual drain on the US economy.

Political conservatives often argue that our economy simply cannot sustain the weight of more undocumented Mexicans and Central Americans. In fact, research at the Pew Hispanic Center shows that 92% of undocumented men are active in the labor force (a higher proportion than among native men) and that most undocumented immigrants see modest improvements in their household income over time. Not surprisingly, those who eventually obtain legal status show far more substantial gains in their income and in the educational attainment of their children.

Myth #5: The situation in Central America is hopeless.

While it is true that many of the children who reach the US border have grown up in difficult and even dangerous situations and ought to be granted a hearing to determine whether or not they should be granted asylum, I have Central American friends (including some from Honduras) who might bristle at the suggestion that every child migrating northward is escaping life in hell itself. The idea that all Central American minors ought to be pronounced refugees upon arrival at the border rests on the mistaken assumption that these nations are hopelessly mired in violence and chaos, and it encourages the US government to throw in the towel with regard to advocating for economic and political improvements in the region.

True, a great deal of violence and hopelessness persists in the marginal urban neighborhoods of San Salvador and Tegucigalpa, but these communities did not evolve by accident. They are the result of years of under-investment in social priorities such as public education and public security compounded by the entrance in the late 1990s of a furious scramble among the cartels to establish and maintain drug movement and distribution networks across the isthmus in order to meet unflagging US demand. At the same time as we work to ensure that all migrant minors are treated humanely and with due process, we ought to use this moment to take a hard look at US foreign policy both past and present in order to build a robust aid package aimed at strengthening institutions and promoting more progressive tax policy so that these nations can promote human development, not just economic growth. It is time we take the long view with regard to our neighbors to the south.