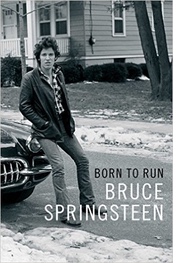

Review of Bruce Springsteen’s "Born to Run"

For

more than a year, Paula Hawkins’s thriller, The

Girl on the Train, has topped the nation’s

bestseller lists. No surprise there. However, earlier this fall

the memoir of an aging American rock star briefly held down second

place on one of the lists. That is noteworthy. I’m talking about

Bruce Springsteen’s autobiography, Born To

Run, issued in late September to coincide

with the musician’s 67th birthday. Born To

Run has risen higher on the bestseller lists

than any previously published autobiography of a rock and roller,

surpassing even Nobel Laureate Bob Dylan’s Chronicles.

For

more than a year, Paula Hawkins’s thriller, The

Girl on the Train, has topped the nation’s

bestseller lists. No surprise there. However, earlier this fall

the memoir of an aging American rock star briefly held down second

place on one of the lists. That is noteworthy. I’m talking about

Bruce Springsteen’s autobiography, Born To

Run, issued in late September to coincide

with the musician’s 67th birthday. Born To

Run has risen higher on the bestseller lists

than any previously published autobiography of a rock and roller,

surpassing even Nobel Laureate Bob Dylan’s Chronicles.

In one sense, Springsteen has been writing his autobiography for over four decades. The lyrics of his songs such as “Growin’ Up,” “Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out,” “Rosalita,” “My Hometown,” “I’m on Fire,” “My City of Ruins,” and, of course, “Born To Run” are decidedly autobiographical. Now, in Born To Run, Springsteen has placed his music within the context of his fast-paced life and offered thoughtful explications of his best-known tracks.

Details of Springsteen’s career have been known since he first achieved fame in the mid-1970s. In contrast to many rock and rollers, Springsteen has seldom turned down a request for an interview and has granted back stage access to music critics and biographers alike. As a result, there are myriad stories about Springsteen in the pages of rock publications, opinion journals and about a dozen books.

Written in fits and starts over several years, Born To Run takes the musician from his troubled childhood in Freehold, New Jersey, through his bar band days on the Jersey Shore, to his explosion on the international music scene and, finally, to his present stature as an eminence grise of American popular music. Like a 3 ½ to 4 hour Springsteen concert, his 500-page tome is sprawling and eclectic. It contains a mixture of pounding action, romantic longing, hometown reminiscences, stories from the road, quirky characters, sex, race, politics, poetry, love, musical creativity, and—perhaps most interesting—introspection. In short, Born To Run offers a tour de force of emotions that should be fascinating to fans of popular music.

But why should historians care about Born To Run? As I have argued elsewhere—see “Bruce: Every American Historian’s Favorite Rock Star” –Springsteen may be one of the two or three most important American singer-songwriters of the last half century. Not only does he hold down a prominent place in the history of American popular music, but he has also developed into an insightful student of his country’s past, and has, on occasion, himself figured in the sweep of historical events. So, when a musician of Springsteen’s stature decides to tell his own story, it behooves those of us who care about American history to pay attention.

Born To Run is not a carefully crafted, elegant memoir. Informal, often profane language, ungrammatical sentences, and an excess of capital letters and staccato punctuation will be off-putting to some readers. But the story moves swiftly and is never dull. It is best to think of Born To Run as a book written in the jangling style of live Springsteen rock anthems such as “Badlands” or “Cadillac Ranch.” The 80 short chapters capture the pace and variety of tracks on the musician’s more than 20 albums. Those fortunate enough to possess several of Springsteen’s records or CDs might consider alternating appropriate musical tracks with a reading of chapters of the autobiography.

One of the things that most impresses me about Born To Run is the author’s unflinching honesty. Early in the book Springsteen provides a graphic description of his father’s harsh parenting style; near the end he describes their touching reconciliation a half-century later. Springsteen is also unflinching in discussing the failure of his first marriage. To quote another popular songwriter, Jimmy Buffett, “Some people claim there’s a woman to blame. But I know, it’s my own damn fault.” Springsteen also provides a candid explanation of the breakup with his first manager. And, of course, there are boisterous accounts of a band of creative musicians on the road. Historians will appreciate how Springsteen interlaces his personal stories with happenings in America since the 1950s.

But it is Springsteen’s description of his battle with depression that offers the most riveting passages in Born To Run. Particularly virulent in the last decade, the funk that afflicted Springsteen—while largely hidden from his fans—threatened many of his closest personal relationships. Springsteen’s plaintive song, “This Depression,” we now know, was much more than a metaphor. Fortunately, skilled therapy, a regimen of proper pharmaceuticals, and the love of his second wife, Patti Scialfa, brought Springsteen through the worst of times.

Other compelling sections of the autobiography describe Springsteen’s delicate relationship with the musicians in the venerable E Street Band. “The Boss” has always been in charge, but he has generally found ways to showcase the talents of Clarence Clemons, Steve Van Zandt, Max Weinberg and the others who have shared the stage with him.

Springsteen has a healthy regard for own his stature, as witnessed by his on-stage swagger. But he also knows his limitations. He recently confessed to an NPR interviewer that his forte as a popular musician is not as a singer or a guitarist but as a songwriter, capable of fashioning memorable stories in simple, precise language. Take, for example, these lines from his haunting “Wreck on the Highway” (1980): “Last night I was out driving/ Coming home at the end of the working day/ I was riding alone through the drizzling rain/ On a deserted stretch of a county two-lane/ When I came upon a wreck on the highway.”

I am pleased to report that Springsteen’s verbal artistry is frequently on display in his autobiography just as in his hundreds of recorded songs.