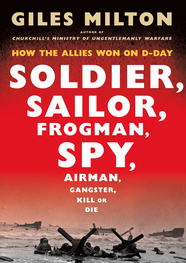

How the Allies Won on D-Day

The following is an excerpt from Soldier, Sailor, Frogman, Spy, Airman, Gangster, Kill or Die: How the Allies Won D-Day.

George Lane [a Hungarian living under a pseudonym who signed up for the elite British-led X-Troop that consisted of foreign nationals whose countries had been overrun by the Nazis] viewed his life in much the same way as a professional gambler might view a game of poker: something to be played with a steady nerve, a dash of courage and a willingness to win or lose everything in the process.

His addiction to risk had driven him to join the commandos; it had also led him to volunteer for a perilous undercover mission codenamed Operation Tarbrush X. In the second week of May 1944, Lane was to smuggle himself into Nazi- occupied France using the cover of darkness to paddle ashore in a black rubber dinghy. His task was to investigate a new type of mine that the Germans were believed to be installing on the Normandy beaches.

Operation Tarbrush X was scheduled for 17 May, when a new moon promised near- total darkness. Lane selected a sapper named Roy Wooldridge to help him photograph the mines, while two officers, Sergeant Bluff and Corporal King, would remain at the shoreline with the dinghy. All four were fearless and highly trained. All four were confident of success.

The mission got off to a flying start. The men were ferried across the Channel in the motor torpedo boat and then transferred to the black rubber dinghy. They paddled themselves ashore and landed undetected at exactly 1.40 a.m. The elements were on their side. The rain was lashing down in liquid sheets and a stiff onshore squall was flinging freezing spray across the beach. For the German sentries patrolling the coast, visibility was little better than zero.

The four commandos now separated, as planned. Bluff and King remained with the dinghy, while Lane and Wooldridge crawled up the wet sand. They found the newly installed mines just a few hundred yards along the beach and Lane pulled out his infrared camera. But as he snapped his first photograph, the camera emitted a sharp flash. The reaction was immediate. ‘A challenging shout in German rang out and within about ten seconds it was followed by a scream which sounded as if somebody had been knifed.’ Soon after, three gunshots ricocheted across the beach.

It was the signal for a firework display unlike any other. The Germans triggered starshells and Very lights (two different types of flare) to illuminate the entire stretch of beach and then began firing wildly into the driving rain, unable to determine where the intruders were hiding.

Lane and Wooldridge scraped themselves deeper into the sand as they tried to avoid the bullets, but they remained desperately exposed and found themselves caught in a ferocious gun battle. Two enemy patrols had opened fire and it soon became apparent that they were shooting at each other. ‘We might have laughed,’ noted Lane after the incident, ‘if we had felt a bit safer.’

It was almost 3 a.m. by the time the gunfight ended and the German flashlights were finally snapped off. Sergeant Bluff and Corporal King were convinced that Lane and Wooldridge were dead, but they left the dinghy for their erstwhile comrades and prepared themselves for a long and exhausting swim back to the motor torpedo launch. They eventually clambered aboard, bedraggled and freezing, and were taken back to England. They would get their cooked breakfast after all.

George Lane and Roy Wooldridge faced a rather less appetizing breakfast. They flashed signals out to sea, hoping to attract the motor torpedo boat and then flashed a continuous red light in the hope of attracting attention. But there was never any response. As they belly- crawled along the shoreline, wondering what to do, they stumbled across the little dinghy. Lane checked his watch. It was an hour before dawn, precious little time to get away, and the Atlantic gale was whipping the sea into a frenzy of crests and troughs. It was not the best weather to be crossing the English Channel in a dinghy the size of a bathtub.

‘Shivering in our wet clothes, we tried to keep our spirits up by talking about the possibility of a Catalina flying boat being sent out to find us and take us home.’ Wooldridge glanced at his watch and wryly remarked that it was the date on which he was meant to have been going off on his honeymoon. Lane laughed at the absurdity of it all. ‘There he was, poor bugger, with me in a dinghy.’

Any hopes of being rescued by a flying boat were dealt a heavy blow in the hour before dawn. As the coastal town of Cayeux- sur- Mer slowly receded into the distance, Lane suddenly noticed a dot in the sea that was growing larger by the second. It was a German motor launch and it was approaching at high speed. He and Wooldridge immediately ditched their most incriminating equipment, including the camera, but kept their pistols and ammunition. Lane was considering a bold plan of action: ‘shooting our way out, overpowering the crew and pinching their boat’.But as their German pursuers began circling the dinghy, Lane was left in no doubt that the game was up. ‘We found four or five Schmeisser machine guns pointed at us menacingly.’ The two of them threw their pistols into the sea and ‘with a rather theatrical gesture, put up our hands’.

They were immediately arrested and taken back to Cayeux- sur- Mer, zigzagging a careful passage through the tidal waters. Lane swallowed hard. Only now did it dawn on him that he had paddled the dinghy through the middle of a huge minefield without even realizing it was there. ‘It was an incredible bit of luck that we weren’t blown to bits.’

The two men feared for their lives. They were separated on landing and Lane was manhandled into a windowless cellar, ‘very damp and cold’. His clothes were drenched and his teeth were chattering because of the chill. He was also in need of sustenance, for he had not eaten since leaving England.

It was not long before an officer from the Gestapo paid him a visit. ‘Of course you know we’ll have to shoot you,’ he was told, ‘because you are obviously a saboteur and we have very strict orders to shoot all saboteurs and commandos.’ Lane feigned defiance, telling his interrogators that killing him would be a very bad idea. The officer merely scowled. ‘What were you doing?’

Lane and Wooldridge had cut the commando and parachute badges from their battledress while still at sea, aware that such badges would condemn them to a swift execution. They had also agreed on a story to explain their predicament. But such precautions proved in vain. The German interrogator examined Lane’s battledress and told him that he ‘could see where the badges had been’. Lane felt his first frisson of fear. ‘They knew we were commandos.’

To read more, check out the book!