The Mysterious Assassination That Unleashed Jihadism

At quarter past noon on 24 November 1989, a red Chevrolet Vega approached the Sab’ al-Layl mosque in Peshawar, Pakistan. As the crowd prepared to greet the arrival, a roadside bomb ripped through the car, killing everyone inside. Peshawar at this time was plagued with violence, but this was no ordinary assassination.

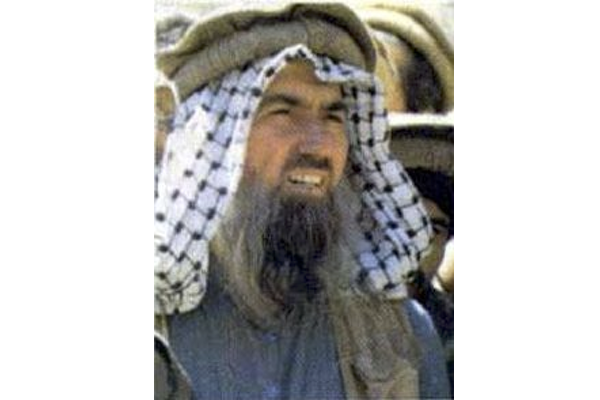

The victim in the passenger seat was Abdallah Azzam, the spiritual leader of the so-called Afghan Arabs, the foreign fighters who travelled in the thousands to fight the Soviets in Afghanistan in the 1980s. The struggle to rid Afghanistan of Russian occupation was viewed in most of the Muslim world as a legitimate case of military jihad, or religiously sanctioned resistance war. A Palestinian cleric, Azzam had joined the Afghan jihad in 1981 and spent the decade recruiting internationally for the war. By 1989, he was a living legend and the world’s most influential jihadi ideologue.

Azzam is not well known in the West today, but he is arguably the father of the jihadi movement, the cluster of transnational violent Islamist groups, such as al-Qaida and Islamic state, who describe their own activities as jihad. Azzam led the mobilization of foreign fighters to Afghanistan, thereby creating the community from which al-Qaida and other radical groups later emerged. His Islamic scholarly credentials, international contacts, and personal charisma made him a uniquely effective recruiter. Without him, the Afghan Arabs would not have been nearly as numerous.

He also articulated influential ideas. He notably argued that Muslims have a responsibility to defend each other, so that if one part of the Muslim world is under attack, all believers should rush to its defence. This is the ideological basis of Islamist foreign fighting, a phenomenon which later manifested itself in most conflicts in the Muslim world, from Bosnia and Chechnya in the 1990s, via Iraq and Somalia in the 2000s, to Syria in the 2010s. Moreover, he urged Islamists –people involved in activism in the name of Islam –to shift attention from domestic to international politics, thus preparing the grounds ideologically for the rise of anti-Western jihadism in the 1990s. Earlier militants had focused on toppling Muslim rulers,such as in Egypt, where the group Egyptian Islamic Jihad killed President Anwar al-Sadatin 1981, or in Syria, where a militant faction of the Muslim Brotherhood launched a failed insurgency against the Assad regime in the late 1970s. Azzam, by contrast, said it was more important to fight non-Muslim aggressors. Azzam himself never advocated international terrorism, but his insistence on the need to repel Islam’s external enemies later became a central premise in al-Qaida’s justification for attacking America.

Azzam’s most fateful contribution, however, was the idea that Muslims should disregard traditional authorities – be they governments, religious scholars, tribal leaders, or parents - in matters of jihad. In Azzam’s view, Islamic Law was clear: if Muslim territory is infringed upon, all Muslims have to mobilize militarily for its defence, and all ifs and buts are to be considered misguided. This opened a Pandora’s box of radicalism, creating a movement that could not be controlled. After all, how do you get people to listen to you once you have told them not to listen to anyone?

Azzam felt the early effects of this problem in his lifetime, but managed to keep order in the ranks through his immense status in the community. After his assassination, however, there was nobody left to rein in youthful hotheads, and the jihadi movement entered a downward spiral of fragmentation and brutality. While the Afghan Arabs in the 1980s had only used guerrilla tactics, some of their successors turned to international terrorism, suicide bombings, and beheadings. The ultra-violence of Islamic State in recent years is only the latest iteration of this process.

So who killed him? Some have suggested a fellow Afghan Arab, such as Osama bin Laden or Ayman al-Zawahiri, but this seems unlikely given the reputational cost to anyone caught red-handed trying to kill the godfather of jihad. Others have blamed foreign intelligence services such as the CIA or the Mossad, but Azzam was not important enough for them. Yet others have mentioned Saudi or Jordanian intelligence, but these countries had no habit of assassinating Islamists at this time. Afghan intelligence (KhAD) had reason to kill Azzam earlier in the war, but not in late 1989. Many have accused the Afghan warlord Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, who resented Azzam’s growing affection for his archenemy Ahmed Shah Massoud, but new evidence shows that Hekmatyar and Azzam were actually close personal friends.

We are left with the Pakistani Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), which had both the capability and a motive. In the late 1980s, the Afghan Arabs had become a nuisance, criticizing Pakistan more openly and meddling in Afghan Mujahidin politics. No hard evidence pins ISI to the crime, but the circumstantial evidence is compelling. The operation was sophisticated and required personnel movement around the site before, during, and after the attack. The location and timing suggest a desire to shock the Arabs, because Azzam could easily have been liquidated quietly in a drive-by shooting. Still, we cannot put two lines under the answer, and the Azzam assassination remains the biggest murder mystery in the history of Islamism.

The story of Abdallah Azzam suggests that a root cause of modern jihadism was the collapse in respect for religious authority among young Islamists in the late 1980s. Azzam initiated it, his disappearance accelerated it, and the repercussions have been devastating. This is also one of History’s many lessons in unintended consequences, for it is a fair bet that neither Azzam himself nor his assassins intended for things to turn out this way.

The question now is whether the genie can be put back in the bottle and religious authority reasserted over young people seduced by jihadism. There are some signs that the excesses of Islamic State has undermined the movement’s appeal, but it is too early to tell whether it is possible to undo the damage of that mysterious blast thirty years ago.