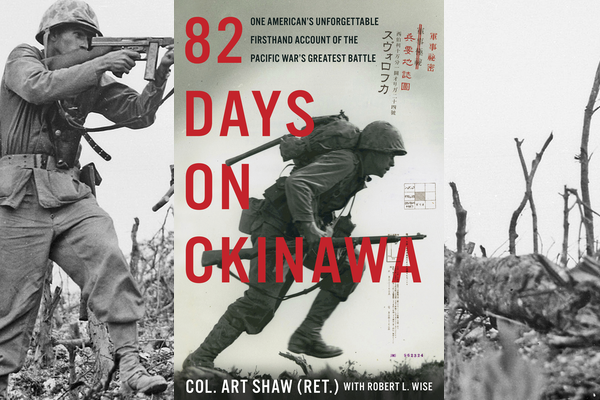

A Price to Be Paid

None of us had any idea how terrible the cost would be before we finished taking Okinawa. The casual observer might have concluded that the landing was so easy, war must be a walk in the park. Some park!

As the postwar decades passed, I realized that the average American’s view of death was shaped by movies and television shows. In thirty minutes, you’d watch a number of people get killed, break for a couple of commercials, get a beer out of the fridge, change the channels, and watch another detective kill some other guys. Finally, you’d turn the set off and go to bed. All those killings were imaginary, impersonal, abstract; they meant nothing. Just show business.

The situation changes when the dead are your buddies, a brother, a friend whom you’d played poker with and shared stories of what you hoped to do when you got home. The cost of war mounts up and takes a staggering emotional toll on every soldier.

Weeks after we had come ashore on Okinawa and fought a good number of battles, Sergeant McQuiston and I were in my jeep driving in the opposite direction from the front lines and following a set of tracks that our boys had cut through the remnant of what had once been a footpath of some sort. The smell of war hung in the air, but by this time we’d gotten used to it and just kept going. We happened onto an area where bodies of soldiers were kept, awaiting burial. After men fell in battle, they were usually carried to the rear and eventually ended up in black body bags.

Somebody had set up a shelter under tarps tied up on wooden poles. Underneath, corpses were stacked like firewood. The pile must have been three to four feet high. The soldiers’ dog tags were fastened on the end of the zippers, the only remaining identification of who they had been.

McQuiston brought the jeep to a halt. The anonymity of the body bags only added to the pathos. Could have been us. We sat there staring at that heap of cadavers. Each one was someone’s son, brother, maybe fiancé, and now they were gone. Forever gone. We stared.

No break for a television commercial there.

Lieutenant Colonel Ed Stare’s Third Battalion of the 383rd Infantry made the most spectacular advance of the day pushing south from the landing beaches. Company I marched along the coast- line until they stopped for a flag raising. Someone had brought an American flag from the States. The soldiers hoisted the flag to signal American sovereignty; the men cheered as the flag went up. Let the Japanese think on that one for a while!

I wasn’t with them at the time, but later the men kept talking about what followed. The experience proved to be so vivid, I couldn’t forget it. The soldiers shared the struggle with me in great detail.

The battalion kept moving; they knew a river was ahead. The men were prepared for a difficult time crossing the waterway. Could be a big-time problem as all the enemy had to do was set up machine guns on the other bank and fire at the approaching soldiers. Amazingly enough, they had forgotten to destroy a bridge. Our men rolled across without missing a beat. They hadn’t gone far up the road when they finally ran into the opposition. About twenty Japanese had set up a machine-gun nest and were waiting for our boys. Battalion I hit the ground and began returning the fire.

Captain Gordon Wheeler yelled that they’d found the enemy.

The gunfire went back and forth while the battalion tried to position itself. Bullets were flying in rapid fire. Soldiers dropped behind boulders or downed trees.

A soldier called back that there weren’t many of them but they were dug in below ground level. We needed to hit ’em from both sides.

The enemy answered with a blast of machine-gun fire.

Wheeler called for the unit to spread out, to split up and work both angles.

The battalion divided on the flanks and started working their way around the opposition. A blast much larger than a simple machine gun ripped through the air. Sounded like they had a 155mm artillery piece over there.

Two American soldiers fell to the ground. A third man screamed and rolled over into a ditch. For thirty minutes intense fire went back and forth. The unit didn’t seem to be making any progress. Casualties were quickly mounting.

The voice of Captain Wheeler echoed through the trees that he needed help. He’d caught it in the leg and couldn’t walk.

Someone called for a medic.

An anonymous man called from the left to keep the captain on the ground.

Men began pulling in behind where Wheeler lay sprawled.

The medic called for them to drag him out and get him behind shelter. Three men pulled the captain across the grass and finally propped him up behind a large boulder.

Wheeler groaned that he’d gotten smoked in the thigh and the pain was killing him.

The medic gave him a shot of morphine. He worked feverishly over the captain, telling him they’d quickly get him out of there.

The soldiers around Wheeler nodded, but a burst of machine-gun fire sent them diving to the ground again. A sergeant crawled over and informed them that they had killed some of the enemy but the rest, though outnumbered, were still dug in below ground level. The battalion couldn’t hit them, and trying would only get them killed. They needed an ace in the hole. Something different.

The radioman crawled over with the phone pack on his back. The sergeant jerked the receiver off and reported the problem. Captain Wheeler had been hit and so had a number of other men. The Japanese weren’t budging. They needed a tank or something big of that order. A weapon that packed a punch. The sergeant listened for a moment before hanging up.

In five minutes, a soldier poked through the trees carrying a long black tube at his side. He said Command had sent him and he had to make it fast because “I’m busier than a one-legged tap dancer over there in my unit.”

The sergeant asked what he’d brought. The soldier answered that he’d show them.

The sergeant beckoned him to follow and they inched through bushes until they stopped behind a fallen tree closer to the enemy. The sergeant pointed out a machine gun there on ground level that was their problem.

The soldier nodded and told them, “Don’t stand behind me. The bazooka has a considerable back blast.”

The soldier lowered himself almost to ground level. Abruptly, the enemy fired a round or two. The sergeant and the bazooka man could hear them jabbering.

After putting his finger to his mouth to signal silence, the soldier rested the long, recoilless antitank launcher on the fork of a scrubby tree. For a second, he carefully aimed low, and then he pulled the trigger. A ball of fire spiraled upward before smoke covered the area around the enemy’s foxhole. The Japanese were history.

The sergeant couldn’t believe the bazooka had knocked them out with one shot.

The two men started inching backward until they rejoined the rest of the squad.

The Japanese wouldn’t be bothering them anymore. The bazooka man saluted and disappeared through the trees and scrub just as he had come in.

By then Captain Wheeler had passed out. Apparently, morphine had done the trick but his leg continued to bleed heavily. The sergeant took a second look.

The sergeant knew that they had to get the captain out of there. A couple of the men carried him out. It was getting late enough in the afternoon that they ought to have been digging in for the night. Fortunately, none of them got hit with that 155mm.

The sergeant who told me this story paused then, caught his breath, and gritted his teeth, cursing the loss of their men. The survivors knew that Wheeler would end up in a body bag with a hundred other guys all laid out under a tarp.

Nobody said anything.

At night we’d sit around and talk, sharing this kind of story. I remember thinking how we were really processing what might happen to us.