"The News Will Get Out Soon Enough": Homefront Jim Crow and the Integration of the U.S. Navy

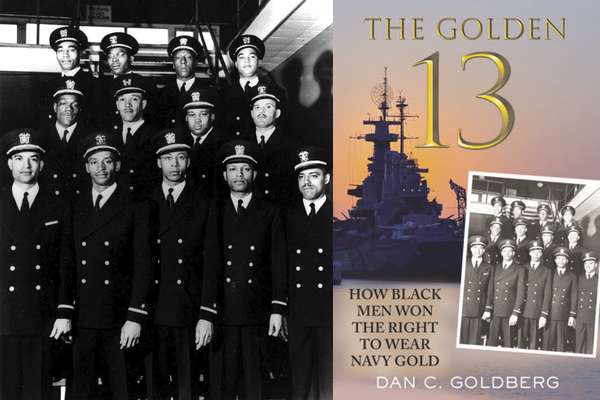

"The Golden Thirteen", the first African-American U.S. Navy commissioned officers. They are (bottom row, left to right): Ensign James E. Hare, USNR; Ensign Samuel E. Barnes, USNR; Ensign George C. Cooper, USNR; Ensign William S. White, USNR; Ensign Dennis D. Nelson, USNR; (middle row, left to right): Ensign Graham E. Martin, USNR; Warrant Officer Charles B. Lear, USNR; Ensign Phillip G. Barnes, USNR; Ensign Reginald E. Goodwin, USNR; (top row, left to right): Ensign John W. Reagan, USNR; Ensign Jesse W. Arbor, USNR; Ensign Dalton L. Baugh, USNR; Ensign Frank E. Sublett, USNR.

This Memorial Day will be particularly poignant given the year’s ongoing events and remembrances marking the 75th anniversary of the end of World War II. As Americans honor those who fought for freedom and democracy in Europe and the Pacific, they would do well to also commemorate the bravery of the thirteen African American men who integrated the U.S. Navy’s officer corps during the war.

Politico reporter Dan Goldberg spent eight years researching the story of these forgotten heroes, intent on bringing them the attention they deserve. In The Golden Thirteen: How Black Men Won the Right to Wear Navy Gold he draws on that research, as well as interviews with the men’s family members, to create a detailed picture of their lives and the opposition they faced, from the pseudoscience that propped up racist policies to the everyday degradation and brutality of America’s Jim Crow era.

The following is adapted from Chapter 9 of The Golden Thirteen.

The headlines today – replete with armed protesters, fury at the government and violence – recall an earlier time in the nation’s history, a period that has been whitewashed over 80 years to hide the stains of sins committed when unity against a common enemy was needed most.

Then, as now, critics of the president felt he was indifferent to their suffering and more concerned with alienating his base than using the bully pulpit to bring the country together.

In 1943, as the Allies took control of North Africa with a succession of victories abroad, race riots were roiling the home front, but one can draw a straight line from some of America’s most shameful days to the Navy’s decision to commission the Golden Thirteen, the first black officers in the U.S. Navy.

For two years, the drafting and subsequent movement of thousands of black men from segregated towns in the South or racially tolerant cities in the North to boot camps in Southern metropolises or overcrowded cities added fuel to embers that had been smoldering for decades.

Riots erupted in the nation’s major urban centers as well as cities critical to defense efforts, including Mobile, Detroit, New York, and Los Angeles. The Social Science Institute at Fisk University counted 242 such outbreaks during 1943, producing what a later observer labeled “an epidemic of interracial violence.”

William Hastie, who had resigned his position as Secretary of War Stimson’s civilian aide in January 1943 because no one was taking his complaints about the mistreatment of black soldiers seriously, told the National Lawyers Guild at the end of May that “civilian violence against the Negro in uniform is a recurrent phenomenon. It may well be the greatest single factor now operating to make 13 million Negroes bitter and resentful.”

Deadly rioting broke out in Beaumont, Texas and Detroit, Michigan where, in early June, more than 25,000 white workers went on strike after the Packard Motor plant promoted three black men to work on the assembly line beside white men. One striker shouted, “I’d rather see Hitler and Hirohito win the war than work beside a nigger on the assembly line.”

Later that month rioting broke out at Belle Isle, a municipal park on an island in the Detroit River. Twenty-five blacks and nine whites were killed, and more than 750 were injured before the riot, the worst of the era, ended.

Letters poured into the White House demanding federal action, and Walter White, head of the NAACP, begged the president to intervene, to marshal the nation as he had done so many times before when a national crisis threatened to overwhelm the republic.

“No lesser voice than yours can arouse public opinion sufficiently against these deliberately provoked attacks, which are designed to hamper war production, destroy or weaken morale, and to deny minorities, Negroes in particular, the opportunity to participate in the war effort on the same basis as other Americans,” White wrote. “We are certain that unless you act these outbreaks will increase in number and violence.”

But the White House made no move, paralyzed by fear of making the situation worse. For every concerned voice that demanded the President intervene to stop Jim Crowism and call for racial equality, there was an equally concerned voice saying it was the very push for racial equality that was causing all these riots, and that Eleanor Roosevelt, in her never-ending quest to promote black men in the factories and the fields, in the Army and the Navy, was responsible for the national discord.

“It is my belief Mrs. Roosevelt and Mayor [Edward] Jeffries of Detroit are somewhat guilty of the race riots here due to their coddling of Negros [sic],” John Lang, who owned a bookstore in Detroit, wrote in a letter to FDR. “It is about time you began thinking about the men who built this country.”

The Jackson Mississippi Daily News declared the Detroit riots were “blood upon your hands, Mrs. Roosevelt” and said she had “been . . . proclaiming and practicing social equality. In Detroit, a city noted for the growing impudence and insolence of its Negro population, an attempt was made to put your preachments into practice.”

Inside the White House, the thought of devoting a Fireside Chat to the subject of race riots was deemed “unwise” by the president’s counselors. At most, Attorney General Francis Biddle argued, the president “might consider discussing it the next time you talk about the overall domestic situation as one of the problems to be considered.”

Roosevelt thought even that too much, and when he gave a Fireside Chat on July 28, one month after the Detroit riots, he devoted not one word to race.

Historians Philip A. Klinkner and Rogers M. Smith have argued that Roosevelt’s famous political antennae failed to pick up the changes taking place in the spring and summer of 1943. Before the war, it was almost universally accepted by white Americans that they were a superior race. Even among the most progressive class, only a few believed much could or should be done about inequality in the near term. In 1942, a National Opinion Research Center Poll found that 62 percent of whites interviewed thought blacks were “pretty well satisfied with things in this country,” while 24 percent thought they were dissatisfied. But by 1943 attitudes were shifting, and a year later, 25 percent of white Americans thought black people were satisfied with their status and 54 percent thought they were dissatisfied.

“True, white southerners were becoming more restive, but it seems clear that in the context of the war, nationally public attitudes on race had shifted enough that [Roosevelt] could have been more outspoken for reform,” the historians argued.

In August, another large riot began—this time in New York City—when Margie Polite, a thirty-five-year-old black woman, was arrested by Patrolman James Collins for disorderly conduct outside the Braddock Hotel on 126th Street in Harlem. Robert Bandy, a black soldier on leave, intervened. He and Collins scuffled, and at some point Bandy allegedly took hold of Collins’s nightstick and struck him with it. Bandy tried to run, and Collins shot him in the left shoulder.

The incident was like a spark to kindling on a hot, sweaty night in the city, the kind where the air is thick and humid, and tempers rise to meet the mercury.

Men and women sitting on their fire escapes seeking relief from the stifling heat climbed down the ladders and formed a mob. They lived in those overstuffed, sweltering tenements because of the color of their skin, because the city wouldn’t let them leave the ghetto. They were packed into apartments like animals, and now that they were ready to die so that the best ideals of their country might live, their countrymen beat and slaughtered them like animals.

The Harlem Hellfighters, the black men who made up the 369th Infantry Regiment, had been sending letters home from Camp Stewart in Georgia in which they told friends and relatives, often in graphic detail, of the gratuitous insults and violence they endured. Harlem’s black press reported on how soldiers were beaten and sometimes lynched in camps across the South. Residents knew of the riots in Detroit and Beaumont. They knew that airplane factories on Long Island, even though desperate for workmen and -women, would not “degrade” their assembly lines with African Americans.

It took 8,000 New York State guards and 6,600 city police officers to quell the violence. In all, 500 people were arrested—all black, 100 of them women. One week later, when the New York Times examined the causes of the riot, it declared that no one should be surprised: “The principal cause of unrest in Harlem and other Negro communities has been [the] complaint of discrimination and Jim Crow treatment of Negroes in the armed forces.”

The Navy responded to the racial tensions by creating the Special Programs Unit. Its mission was to coordinate policies and protocols for black sailors so that they were used to their full potential and protected—as much as possible—from humiliation and violence.

At its helm was Lieutenant Commander Christopher Sargent, a thirty-one-year-old who had clerked for Supreme Court Justice Benjamin Cardozo and worked in the law firm of Dean Acheson, a future secretary of state. Sargent would later be described as “a philosopher who could not tolerate segregation,” and he waged “something of a moral crusade to integrate the Navy.”

Unlike many more senior officers, Sargent thought the war was the best time to integrate the fleet and told superiors that racial cooperation would create a more efficient fighting force.

Among the unit’s highest priorities was to see to it that black men were no longer bunched together at ammunition depots or other installations with little real work to do, and that graduates of Class A naval training schools were given proper assignments.

The Special Programs Unit then convinced Admiral Ernest King, chief of naval operations, to place 196 enlisted African Americans along with 44 white officers on the USS Mason, a destroyer escort expected to traverse the Atlantic on convoy missions. The ship, still under construction at the Boston Navy Yard, was named for Ensign Newton Henry Mason, a fighter pilot shot down during the Battle of the Coral Sea. Many in the Navy gave it a different name: “Eleanor’s folly” they called it, another slight aimed at the First Lady for her advocacy of integration.

Manning the ship did not, of course, represent total integration or full equality. The ship would have all-black crews serving under white officers. White and black men would still sleep in different quarters and eat at different tables.

“We are trying to avoid mixing crews on ships,” Navy Secretary Frank Knox told reporters. “That puts a limitation on where we can employ Negro seamen.”

Still, the black press heralded the announcement. For years, civil rights leaders had said that the right to fight and die for one’s country was a crucial step toward making the United States a more perfect union. Having black sailors outside the messman branch serve at sea marked “a distinct departure from present Navy policy and is the culmination of a five-year fight,” the Pittsburgh Courier told its readers.

But one problem remained beyond the unit’s reach, one symbol of inequality so glaring that it outshone all other successes: at the end of 1943, there were no black officers.

The job of convincing Navy Secretary Frank Knox that it was finally time to commission black officers fell to Adlai Stevenson, the secretary’s speechwriter and confidant.

On the question of integrating the officer corps, Stevenson explained to Knox, an efficiency expert, that refusing to commission black men was now unquestionably inefficient. The Army, he said, was still recruiting better-educated, better-disciplined black men in large part because that branch offered a path for advancement. If the Navy wanted to keep up, it would have to consider commissioning African American officers.

There were 60,000 black men in the Navy, and 12,000 more were entering every month, Stevenson wrote to Knox on September 29, 1943. “Obviously, this cannot go on indefinitely without accepting some officers or trying to explain why we don’t. I feel very emphatically that we should commission a few Negroes.”

Stevenson suggested “10 or 12 Negroes selected from top notch civilians just as we procure white officers.” He ended his memo by telling Knox, “If and when it is done, it should not be accompanied by any special publicity but rather treated as a matter of course. The news will get out soon enough.”

Excerpted from The Golden Thirteen: How Black Men Won the Right to Wear Navy Gold by Dan C. Goldberg. Copyright 2020. Excerpted with permission by Beacon Press.