Honor the Work of Brazil's Villas-Bôas Brothers by Protecting the Amazon's Indigenous

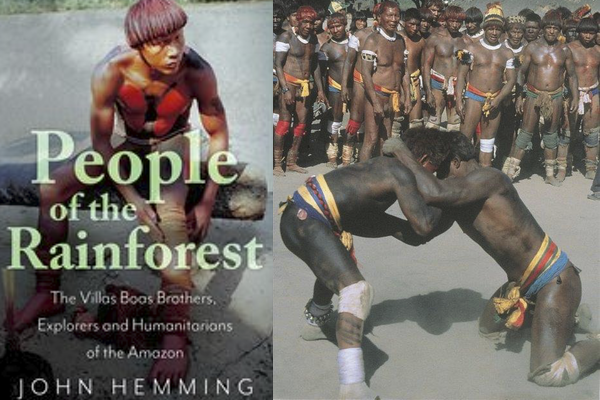

Xingu men wrestle. Photo by Author

Brazil’s 800,000 indigenous people, in over two hundred tribes, are under the greatest threat that they have seen in recent times. President Jair Bolsonaro claims that they want to leave their communal societies and ancient cultures, to make money as ordinary materialistic Brazilians. He wants to open their territories to mining and other commercial exploitation. And he favours destroying tropical rain forests by penetration roads, colonisation schemes, logging and hydroelectric dams. Every indigenous leader – world figures like Raoni and Megaron Metuktire, Davi Yanomami, Aritana Yawalapiti, and scores of younger chiefs – as well as every anthropologist and environmental activist knows that he is totally wrong. I, who have been with forty-five indigenous peoples, and written a three-volume 2,200-page history of their travails during the past five centuries, know that there is not a single people who want to leave their lands and communal way of life.

Until now, Brazil could be proud of its recent treatment of indigenous people. Its 1988 Constitution declares that these are descendants of the original Brazilians. It protects their way of life and all the lands that they need for their physical and spiritual wellbeing. The result is some seven hundred indigenous territories, for 240 ethnic groups, covering almost 1,150,000 square kilometres – an area as large as the original European Union. Much of this is forested, a significant portion of the world’s surviving tropical rain forests. Earth’s richest ecosystem is essential for sequestering carbon, generating rain and combating global warming. To paraphrase Winston Churchill: rarely have so many owed so much to so few – the rest of humanity to the indigenous peoples, custodians of the forests within which they alone can live sustainably.

The system that is now under acute threat is to a large extent the creation of the three remarkable Villas-Bôas brothers, the subjects of my new book People of the Rainforest. In the late 1940s the President of Brazil announced a great national venture, to cut into its Amazonian forests rather than explore them by river, as had been done during the previous four centuries. The Villas-Bôas brothers were the only middle-class young men excited by this expedition. Each left a desk job in São Paulo, travelled for 1500 kilometres to join it and, with their dynamism, education and leadership potential, were soon in charge. After eighteen months of tough trail-cutting across unexplored dangerous ‘Indian country’ the expedition reached its goal: the upper Xingu River, in the forested heart of Brazil. After leading this national endeavour, the brothers made further challenging explorations, and they opened a chain of airstrips across the endless expanse of forests. All this made the glamorous brothers their country’s most famous explorers.

The headwaters of the upper Xingu were inhabited by a dozen indigenous peoples, who had remarkably survived into the mid-twentieth century with their elaborate cultures intact. The Villas-Bôas soon progressed from being government explorers to helping these splendid Indians (as they were then known). They spent thirty years among them, and the rest of their lives campaigning for indigenous rights. Despite having no anthropological training or experience (or perhaps because of this), the brothers evolved a new modus operandi. They treated Indians as equals, sometimes jokingly and affectionately, and saw themselves as friends and helpers rather than colonialist representatives of the central authorities. Leonardo, the youngest brother, died during a 1961 heart operation, but the surviving Orlando and Cláudio each had a ‘post’ 150 kilometers apart on the Xingu river. They visited villages only when invited, usually for a festival or ceremony; but Indians came to them at any time and they knew all about tribal politics. These methods were adopted throughout other indigenous posts.

The well-ordered societies of the Xingu’s sources were under attack from warlike tribes in surrounding forests and rivers. So during the 1950s and ‘60s the Villas-Bôas brothers made a series of expeditions to contact and pacify five of these peoples. Each first-contact was very tough and often dangerous – adventures that made Indiana Jones’s exploits look like a stroll in the park. The last was to win over the belligerent Panará people. There was an unsuccessful five-month expedition in 1967-68 followed by a thirteen-month attempt that finally achieved face-to-face contact in 1973. These ventures endured three rainy seasons, when explorers are never dry in torrential rains. The result was what is known as the Pax Xinguana: the brothers got the indigenous peoples to unite in the face of encroaching national society. Their contact techniques have been used by all subsequent approaches to isolated peoples.

The Brazilian Air Force ran a service of regular flights by WW2 C-47 Dakotas to the string of forest airstrips. The brothers could thus exclude unwelcome adventurers, even missionaries; but they could invite anthropologists and serious journalists. The combination of handsome Indians, famous glamorous explorers and idyllic forests was a media dream, so that the Villas-Bôas got superb coverage. This completely changed public opinion, to see indigenous societies not as embarrassing primitives but as a source of pride in purely Brazilian culture. Politicians took note.

In 1952 Orlando Villas-Bôas and three others had a radical idea: to get a vast tract of forests protected, just for the indigenous peoples living in them. Nine years of frantic political and media struggle ensued, until in 1961 Brazil elected a dynamic young President, Jânio Quadros – who happened to be family friend of the Villas-Bôas in São Paulo and had seen their achievements in the Xingu. So Quadros rammed through, as a presidential decree, the 26,000-square-kilometre Xingu Indigenous Park – the first of its kind in the world, and the prototype for similar huge reserves throughout Amazonia that have had such a powerful environmental impact on a global scale.

From the outset, the brothers knew that change was inevitable. But their mantra was: ‘Change, but only at the speed the Indians want’. The challenge was to make indigenous peoples aware of what was offered by national society – but without losing their pride in their way of life. In this they succeeded brilliantly, bringing their tribes from pre-literate, pre-metal hunting and fishing to co-existence with modern life – in a mere two generations. Most of the grand old indigenous spokesmen are their protégés, and young Xinguanos are totally computer-literate. But they all know that their ancient communal societies, in their beloved forests, are infinitely preferable to life on the rough settlement frontier.

The Villas-Bôas left the Xingu in 1976, by then ‘national treasures’ loaded with medals and honours. They were twice nominated for Nobel Peace Prizes, with every Amazonian anthropologist, headed by Claude Lévi-Strauss, endorsing them. They wrote and lectured tirelessly for the cause throughout the last quarter of the twentieth century, and helped to get the favourable clauses into Brazil’s Constitution. So they would be appalled by President Bolsonaro’s threats to everything they and their indigenous friends achieved.