Of Course Kamala Harris is a Citizen

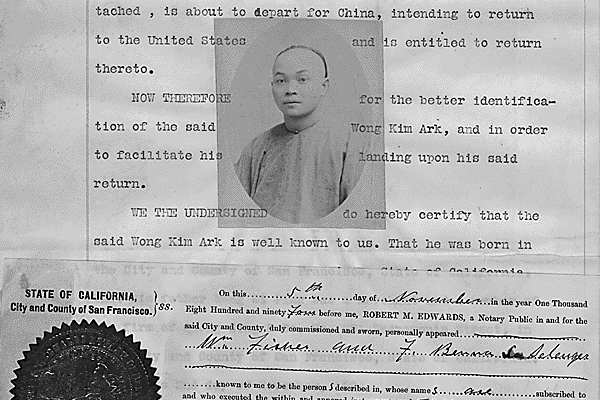

Notarized affidavit of witnesses attesting to Wong Kim Ark's birth in San Francisco, 1894

It didn’t even take a day for the attacks against Senator Kamala Harris to begin. In reality, they began in earnest weeks ago, when it became clear she was at the top of Joe Biden’s shortlist for running mates. Yet, quickly following the announcement that Harris would be the Vice-Presidential nominee on the Democratic ticket, a new wave of attacks began, different than those before. In a redux of birtherism, Dr. John C. Eastman and his fellow conservatives have been hard at work trying to invalidate Harris’s citizenship status.

What citizenship actually is has never been legally defined in U.S. history, but who is a citizen was finally sketched out under the 14th Amendment of the Constitution, which states citizenship is granted to “all persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof.” This has generally been understood to mean something quite simple: If you are born on U.S. soil, you are a citizen. Yet, in recent years, conservatives have pushed back against this understanding of citizenship in order to argue the children of migrant immigrants, so-called “anchor babies,” are not in fact eligible to be citizens.

Eastman’s argument rests on U.S. v. Wong Kim Ark, a late-19th Century Supreme Court case. The case involved the citizenship status of Wong Kim Ark, a child of Chinese immigrants, who after visiting China was denied reentry into the U.S. under immigration laws which heavily restricted Chinese immigration. His citizenship status, which should have precluded him from anti-Chinese immigration laws, was not recognized by the government. The U.S. argued because his parents were not citizens of the United States, but subjects of China, Wong Kim Ark was in turn a non-citizen, despite being born in San Francisco.

The Supreme Court ruled in Wong Kim Ark’s favor, stating any child born on U.S. soil of parents who “have a permanent domicile and residence in the United States” are still automatically considered citizens. It is here that Eastman and his merry band of conservatives find their loophole. Echoing Donald Trump’s repeated attacks on birthright citizenship and “anchor babies,” Eastman claims Harris can’t be a citizen, because her parents were ineligible to confer such a status onto her. In Eastman’s mind, it seems likely that Harris’s parents were “temporary visitors, perhaps on student visas,” and therefore not permanent, domiciled residents. The fact that visas did not exist at the time of Wong Kim Ark, and therefore attempting to shoehorn the wording of the Court’s 1898 decision into our modern system is fruitless, seems of little concern to him though. Simply put, if Harris’s parents were not permanent residents, and “subject to the jurisdiction” of the United States, then the Senator could not have been a natural-born citizen; one of the most important qualifiers for being President and Vice-President.

This line of reasoning has increasingly been deployed by conservatives to attack birthright citizenship, and particularly the citizenship of children born to undocumented migrants. Harris is simply the most high profile target of a political party intent on excluding and driving immigrants out of the United States by dismantling, or ignoring, birthright citizenship. In this, conservatives mirror the very history Eastman attempts to use to bolster his points. In his argument, he points out that the modern view of birthright citizenship didn’t develop until after Harris was born, and uses the expulsion and repatriation of Mexican families as evidence. In his loose interpretation of history, the U.S. born children of Mexican migrant farm workers weren’t considered citizens throughout the middle part of the 20th Century. Yet he fails to speak about how this wasn’t official U.S. policy, and the unlawful expulsion of U.S.-Mexican families was done by local officials, through extralegal mob violence, only tacitly and unofficially endorsed by the national government keen on shoring up political support among border state residents.

It is in this and other areas that Eastman and conservatives’ attempt to marshal history to their defense illustrates just how much their arguments are actually devoid of any real historical understanding. In speaking about the jurisdiction section of the 14th Amendment’s Citizenship Clause, Eastman fails to recognize this was primarily aimed at Native Americans rather than the children of immigrants. What discussion there was over immigrants, chiefly Chinese immigrants, was split, with more people thinking the amendment would not only confer citizenship to immigrant children, but also that current U.S. law already functioned that way. The Supreme Court would eventually come down on the side of those who saw the 14th Amendment as conferring citizenship to anyone born on U.S. soil, despite the status of their parents.

Furthermore, Eastman employs a selective reading of Wong Kim Ark, failing to mention the Supreme Court actually lays out exceptions to their ruling, none of which apply here. As the Court explicitly said, there were only four exceptions to the 14th Amendment’s conferral of birthright citizenship: children of foreign diplomats, children born on foreign vessels, or children born to hostile enemies currently occupying any part of the United States. The fourth “single additional exception” extended to the children of Native American tribes who were not “subject to the jurisdiction” of the United States.

Not only this, but Eastman attempt to present the language of the dissenting opinion in Wong Kim Ark as the actual law on the books. He repeatedly mentions that people must be subject to the “complete” jurisdiction of the United States, despite the fact that the 6-2 majority opinion does not employ this language. In fact, it is the dissenting opinion which continually uses the language of “complete” jurisdiction in order to deny Wong Kim Ark’s citizenship, arguing since his parents were still subjects of China, could not renounce this status, and could not become U.S. citizens under current law, that they were only under “partial” jurisdiction. Eastman’s presentation of the dissenting opinion as settled law is not only incorrect, but unbecoming of someone who is supposedly a scholar of constitutional law.

It is, however, even harder to take Eastman’s supposed legal argument seriously when one considers his past comments. After all, his views on who is and isn’t a natural-born citizen, and thus eligible to be President, are inconsistent. He holds that Senator Harris’s claims are flimsy, yet, in 2016 he described the debates over Senator Ted Cruz’s eligibility as “silly.” Relying on the same historical and legal precedents, Eastman concluded Cruz, whose mother was a U.S. citizen, is a natural-born citizen even though he was born in Canada. Having alleged that “no serious constitutional scholars adheres to the view” that the natural-born citizen clause requires birth on U.S. soil, Eastman would nonetheless have us believe that Senator Harris’s claims on presidential eligibility are far weaker than Senator Cruz’s, despite the fact that the former was actually born on U.S. soil.

Furthermore, it’s a wonder that Eastman is taking the time to write op-eds in Newsweek challenging Harris’s eligibility to be Vice-President. The logical end of his argument is that Harris is not a U.S. citizen, leading him to not only challenge her presidential eligibility, but senatorial eligibility as well. And so, if Eastman truly believes that Harris is not a U.S. citizen, but has been illegally squatting in this country for 55 years, why stop at challenging her presidential eligibility? Should Eastman not simply drop the pen, pick up the phone, and report the Senator to Immigration and Customs Enforcement?