The Paradox of Executive Underreach

In the past sixty years, a recurring concern of presidency scholars has been the rise of presidential power and the ongoing threat of executive overreach. As the Framers warned us, the potential abuse of power by presidents and the need to be vigilant against usurpations of power would require a separation of powers system, a strong Congress, an independent judiciary, and a citizenry willing to serve as guardians of the republic.

Having fought a war over executive tyranny in the form of the British King, the Framers were intent on limiting the threat of a runaway executive, and so serious was their concern of the potential rise of executive power that in their first constitution, The Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union, no executive office was created. The Congress possessed what executive power there was, and while it is understandable that the Framers feared the executive, they soon came to recognize that while the threat of abuse existed, still, some form of an executive was necessary to achieve good government.

This original absence of an executive reflected the tyrannophobia of the age. But their executiveless system proved unworkable in practice, and the Framers reluctantly recognized that however potentially dangerous to their liberties the executive might be, not having an executive guaranteed ineffective government.

But the nation would not have a powerful executive. If too powerful an executive led to tyranny, too weak an executive led to a government unable to function. By the late 1780s, the Framers expressed a need for a new government that accounted for, among other things, the twin evils of executive overreach, and the just as dangerous potential for executive underreach. So the Framers created a limited presidency with few expressed powers, within a republican form of government with checks and balances and a separation, as well as a sharing of power. This reflects the Framer’s recognition of what has come to be called the “Goldilocks Dilemma” of presidential power: this power was too hot, this power too cold, it was difficult to get presidential power “just right.”

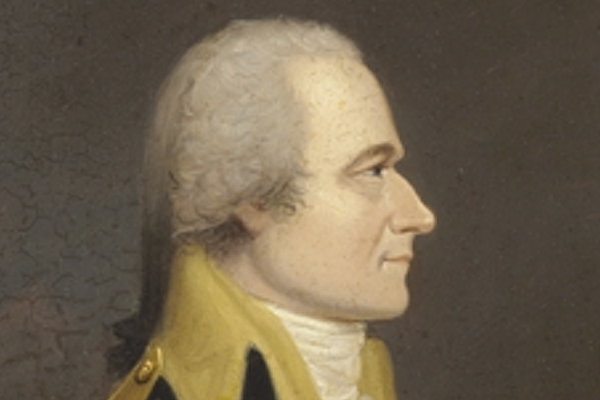

No Framer has written with more exacting clarity about the newly invented presidency than Alexander Hamilton. His explanation of the office in the Federalist Papers remains the single best source for discerning the intent of the Framers regarding the presidency. Hamilton, in Federalistnumber 70, noted the need to give the new presidency energy, while also binding the office to republican values and limitations. “There is an idea,” he wrote, “which is not without its advocates, that a vigorous executive is inconsistent with the genius of republican government.” Later he adds that “Energy in the executive is a leading character in the definition of good government.” He then writes that “A feeble executive implies a feeble execution of the government. A feeble execution is but another phrase for a bad execution; and a government ill executed, whatever it may be in theory, must be, in practice, a bad government.”

What, Hamilton asks, “are the ingredients which constitute this energy? How far can they be combined with those other ingredients which constitute safety in the republican sense?” Hamilton lists these ingredients: unity, duration, an adequate provision for its support, and competent powers. Thus, for Hamilton, the new presidency represented energy in a republican sense. It was a presidency of some powers, but also republican limitations.

History validates Hamilton’s hopes and fears. Yes, a president needed energy, but examples of executive overreach by presidents such as Lincoln during the Civil War, Wilson during World War I, FDR during the Depression and World War II, Nixon in Watergate, Reagan in the Iran-Contra scandal, George W. Bush during the war against terrorism, Obama with targeted killings, and Trump with the travel ban, family separations, at the Mexican border, and DACA, all point to the need for republican limits if we are to control the pernicious effects of a too-powerful presidency.

But of course, the inverse is just as true: too feeble an executive is the other side of the coin from a runaway presidency, and presents a set of problems all its own. If, as Hamilton asserts, a feeble executive is merely another way of saying “a bad government,” then we must also guard against executive underreach.

Executive underreach is defined as the conscious failure to do one’s due diligence or a failure to address serious public problems in cases where the public expects a president to lead, a president’s authority allows the president to act, and the executive has some capacity to have an impact, yet due to indifference or failure to recognize need, an abdication of leadership and responsibility takes place.

As the Civil War approached, President James Buchanan failed to rise to the challenge and asserted that while he opposed secession of the Southern states, he did not believe he had the constitutional authority to act. He fiddled while the Union burned. That which paralyzed President Buchanan animated his successor, Abraham Lincoln, a case of underreach leading to overreach.

A more recent case of executive underreach can be seen in President Trump’s tepid and largely ineffective response to the outbreak of COVID-19. The President initially dismissed or downplayed the severity of the pandemic, arguing that it would go away in a few days. In doing so, he lost precious time that might have been devoted to mitigating the deadly effects of the virus. But as the virus spread and death-counts mounted, the President shifted gears, attempting to shift responsibility (and blame) to the states. Within a three-day period, President Trump went from claiming he had “absolute authority” and that his power was “total” to deal with the pandemic, to handing the hot potato over to the states and retreating into the White House.

Early on, the Trump administration ignored the warning signs. When they should have been acting, they were busy shifting blame and responsibility. Even as it became clear that the virus was not under control and was spreading, the President retreated, his leadership was MIA. His “ostrich approach” of digging his head into the sand and hoping it would all just go away or that the states would handle everything contributed to the spread of the deadly virus and the deaths of thousands. The warning signs were clear – health experts alerted us to the growing crisis. The numbers told the story – increases in cases and deaths that could not be ignored. A failure of leadership was obvious – the virus was spreading and the President was in denial. Safety measures were repeatedly discussed – yet the President modeled bad behavior by rarely wearing a mask or practicing social distancing. The President walked away from his responsibilities.

The problem of executive overreach stems from ambitious or power-hungry presidents, determined to bypass the checks and balances built into the constitutional system, and govern either alone or in a manner that bypasses the Congress or ignores the courts. This leads to what historian Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. described as an Imperial Presidency. The problem of executive underreach stems from a president who is either corrupt, incompetent, or unwilling to face up to the duties of the office. This creates not an Imperial presidency, but an Imperiled presidency. And if the Framers were primarily concerned with overreach, they did not ignore the dangers of underreach. Alexander Hamilton, in Federalist number 68 however, seemed to downplay the dangers of a rogue or incompetent person reaching the presidency. He wrote that “This process of election [the Electoral College] affords a moral certainty that the office of President will seldom fall to the lot of any man who is not in an eminent degree endowed with the requisite qualifications.” Seldom. What happens when the seldom becomes the here and now?

This Goldilocks dilemma can thus, at either extreme, pose a threat to the republic, and calls upon us to revisit the key question raised by Hamilton in Federalist number 1: does this new constitution “decide the important question, whether societies of men are really capable or not of establishing good government from reflection and choice, or whether they are forever destined to depend for their political constitutions on accident and force.”