The Troubling History of a Black Man's Heart

To better understand the longstanding inequalities and injustices still plaguing America’s healthcare system, it helps to travel back in time to ancient Greece and heed the warnings of that early medical ethicist, Plato.

“The greatest mistake in the treatment of diseases,” he said, “is that there are physicians for the body and physicians for the soul, although the two cannot be separated.”

Similarly, the greatest mistake in trying to heal long-held suspicions of American medicine held by Black Americans is to forget that the heart of good medicine beats with trust.

I was reminded of this historical legacy last spring when some Black Americans said they were reluctant to accept free testing for the novel coronavirus. One young man near where I live in Richmond, Virginia told the Washington Post that his older employer had discouraged him from getting tested. “This might be a Tuskegee-type trap,” he told him, referring to the notorious study of Black men in Alabama that left them suffering from syphilis. Sadly, although penicillin became available to treat the disease, the men were allowed to suffer and sometimes die during a four-decade-long study that didn’t end until 1972.

As someone in college in the 1970s, I found it astounding that such a dark chapter in American medical history -- smacking of racism, eugenics and Hitler-era torture – was still happening. It would take another quarter century before President Bill Clinton issued a formal apology in 1997.

More apologies – and perhaps reparations – may lie ahead as journalists and historians keep turning up secrets from our not-so-distant past. My own eyes were opened to the legacy of mistrust in communities of color during the three years I spent investigating the tragic saga of a black man who entered a major hospital in Richmond in 1968 during a period not unlike today—marked by street protests, police brutality, and racial polarization after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King.

On the evening of May 24, 1968, a factory worker named Bruce Tucker was celebrating the end of his workweek by having drinks with friends. As he chatted with them, he lost his balance and fell from a wall. He sustained a serious head injury and, after initially resisting efforts to help him, was rushed to the emergency room of what was then called the Medical College of Virginia (today it’s VCU Health).

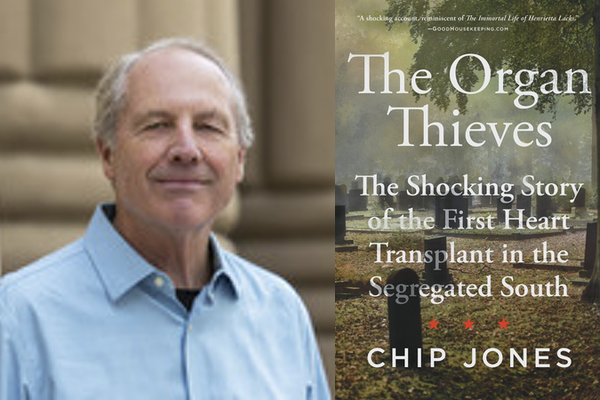

In my new book, The Organ Thieves: The Shocking Story of the First Heart Transplant in the Segregated South, I argue that the intense, worldwide competition to perform heart transplants during the 1960s set the stage for the wrongs done to this seriously injured patient and to his family. For at the same moment MCV’s transplant surgeons got the official approval to remove life support, Mr. Tucker’s own family and friends were frantically searching for him.

As two leading transplant ethicists, Robert M. Veatch and Lainie F. Ross, wrote in their authoritative 2015 book, Transplantation Ethics, “Many interpret the case as establishing a brain-oriented definition of death for the state of Virginia, but it could equally be viewed as the first case where a ventilator is disconnected for the purpose of causing the death of the patient, by traditional heart criteria, in order to procure organs for transplant.”

In 1968, unlike today, there was no effective national organ procurement system in place in the state-owned hospital where Tucker breathed his last. This essentially gave free rein to the transplant surgeons to proceed with what they thought was best at the time for a seriously ill white patient: that is, to remove Tucker’s beating heart and place it in the man’s chest (the white businessman, Joseph Klett, survived for only eight days after receiving the heart, which was either “donated” or “stolen,” depending on one’s point of view).

This experimental operation, with its deep racial overtones, led to the first “wrongful death” lawsuit brought over a heart transplant in the U.S. As Veatch and Ross commented, “The doctors were exonerated, but it is unclear whether the court held that the doctors had the authority to turn off the ventilator on a still-living patient in these circumstances or whether it held that Tucker was already dead based on brain criteria.”

Based on my own reading of court and archival records, first-person interviews with surviving doctors, lawyers and some Tucker family members, here are a few more salient points about a case that led to the passage of Virginia’s first law recognizing the concept of “brain death” in 1973.

Though Bruce Tucker was still awake upon admission to the hospital with normal vital signs, the 54-year-old factory worker fell into a coma. With that, he was quickly identified by the night staff as a potential “donor” in what would be the first heart transplant in Virginia history.

The pressure to attempt this still-experimental procedure was intensified by the fact that only six months earlier a recent guest at MCV -- Dr. Christiaan Barnard of South Africa – had won the heart transplant race. This achievement in late 1967 turned Barnard into an overnight celebrity. The acclaim began to gnaw at the Richmond transplant surgeons – especially chief of surgery David Hume, who’d invited Barnard to MCV. In the afterglow of the South African’s stardom it’s easy to see why the Virginians felt left out of one of the greatest feats in the medical history.

Against this backdrop of competition, professional rivalry, and institutional aspiration, the odds for equal treatment were stacked high against a black man with a head injury and alcohol on his breath. Bruce Tucker was easily seen as another “charity patient” who wouldn’t pay his bills, as one of the doctors who was on the scene later told me.

Tucker’s social invisibility, as other scholars have noted, led to the conclusion by the hospital staff that this Black man with no one coming to claim him had little chance of recovery. However, with his heart beating strongly and other vital signs normal, he was quickly seen as a prime candidate to be an organ donor.

In the end, the decision to take out Bruce Tucker’s heart—along with his kidneys—was approved by a junior medical examiner on duty that fateful weekend. Adding to the family’s sense of loss was the frantic search by William Tucker, a nearby storeowner, to find his older brother before anything was done to him. Unfortunately, the cobbler arrived a few hours too late. It would be left to a local funeral director to break the gruesome news about Bruce’s missing heart and kidneys.

The Organ Thieves shines a bright light on this long- forgotten medical drama that played out on a stage filled with racial discrimination, political and cultural polarization. It raises unsettling and still-unresolved questions about how someone could be treated in such a cold-hearted way.

While American medicine has improved a lot since then – for example, by ensuring “prior consent” before organs are donated – many of the injustices described in my book can be seen today when Black Americans share their own sense of suspicion and mistrust of the health care system, particularly during the pandemic.

Since my book has been published, I’ve been heartened to hear from readers and reviewers alike that The Organ Thieves has revealed a long-forgotten chapter in the history of American medicine. This, in turn, has fostered important conversations about working to bring long overdue changes to our health care system.

For nobody deserves to be treated like Bruce Tucker.