Who Owns Churchill?: Three Mythic Configurations

We sent our manuscript, The Churchill Myths, to Oxford University Press on 24 July 2019, the very day that Boris Johnson became prime minister of the United Kingdom. The manuscript had been in conception, and came together in various drafts, for almost exactly a year: its completion and the dramatic shift in the political world was no coincidence. The conjunction of the two felt strangely unnerving to us, when for once our own historical study appeared unusually punctual, addressing immediately the contemporary moment.

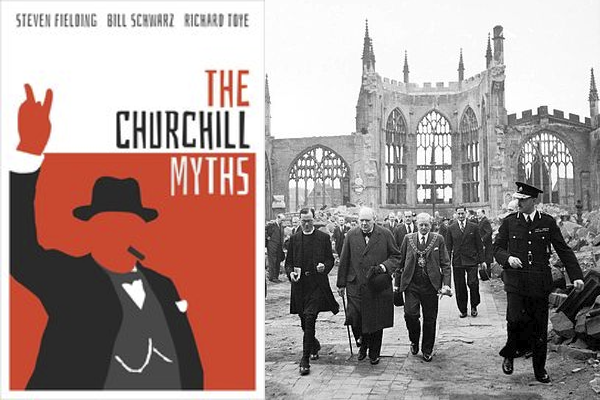

Johnson’s career had become increasingly identified with Churchill’s memory, not least in his own dreams, which he proved keen to share with the nation. His bestselling book, The Churchill Factor (2014), signalled not only a literary but a political event. Since Churchill retired from office in 1955 many politicians, in the UK, the USA, and elsewhere, have endeavoured to appear “Churchillian.” Like Johnson, they have wished to exploit Churchill’s reputation as steadfast, determined, and resolute. Yet although the core of Churchill’s image -- indelibly linked with his cigar and V-sign -- has remained constant, there have been significant historical changes in how successive political generations have deployed him.

This is why we refer to myths in the plural. Churchill is constantly being reshaped in public debate and put to new political uses. How he is understood will continue to evolve in our own present, as well as in the future.

We suggest, speaking broadly, that there are been three overriding phases in the mythic configurations of May 1940, with the figure of Churchill himself assuming ever greater prominence as the story evolves.

First, during the global crisis of May 1940, when the Nazi invasion seemed a matter of hours away, the place of Churchill in the telling of the story was not what we would expect. Mythic Churchill was present, of course, not least in Churchill’s own self-dramatizations. But this “Great Man” version of history had to compete with the role of “the people” as radical, and as the principal historical actor, with Churchill himself assuming a significant, but not an absolute, part in the story. This idea of ‘the people’ itself had mythic properties, while Churchill was relegated to acting as an adjunct to the larger popular mood, the one that was expressed in Labour’s 1945 election victory.

Second, from the late 1940s – that is, after Churchill lost the premiership – mythic Churchill really takes off. His own hand in the making of this state of affairs was not slight. In these years, Churchill became the means by which the compact between the state and the people could be harmoniously accomplished, magically unified through the commanding person of Winston Churchill. This is when Churchill himself became the totemic distillation of the nation.

In the last twenty years, thirdly, a new configuration of meanings has emerged. This is partly evident in Boris Johnson’s own revision of the story. Churchill still remains the incarnation of “the people.” But this is a more nativist, more belligerent people which is understood to be – not in harmony – but in contention with the state. This reimagining of Churchill sees the “respectable,” mainstream Conservatives as the enemies and betrayers of the people. The historic Conservative Party is re-imagined as the enemy within.

The tangled relationship with Europe lies behind this. Johnson himself, when adopting the garb of Churchill, does so as a “man of destiny,” saving the people from the corruptions of the old Establishment, which includes both the advocates of Europe and the institution of the Conservative Party. This signals a more Jacobin, intemperate, and resolutely populist politics.

When we were completing the book we knew Johnson’s electoral triumph was not the end of the story. But we could not have possibly anticipated how the explosion of Black Lives Matter would come to represent such an electric current in the public life of the British nation. History can always take us by surprise. Churchill, this time as the “racist,” is again emphatically a charged sign in the polarization of contemporary British politics.

But notwithstanding these divisions Churchill as transcendent figure remains powerful. When his name is uttered in public, chances are that it will be underwritten by faith in the empire as the unilateral medium for the benediction of others. Repetition of Churchill as the nation’s story runs deep. Its popular variations are impervious to critique. It’s not that contrary voices don’t exist. They do, and frequently they’re heard. It is, rather, that the Ur-story reproduces itself regardless of whatever manifestations of dissidence cross its path. The more repetitious it becomes, the more impregnable it is, and the further it departs from historical realities. In its telling, thought is eviscerated. The past is acted out, with no need for reflection. The story – the myth -- obliterates history. The story tells itself.

Churchill becomes the means for the nation’s exceptionalism to exert its authority. There persists a puzzling faith in the notion that England, providentially, has been peculiarly immune to the existential darkness which shadows modern selfhood. Whether anyone actually believes this or not, as a literal truth, may be unlikely. But its echoes nonetheless persist. This is a voice heard in different frequencies. It constitutes a barely conscious substratum of popular experience, flaring into the light of day in tabloid headlines. It turns on an attachment to the protocols of an English fundamentalism. When critics point to the dark matter in the nation’s past -- to the violence of colonialism, to enslavement, to the racialization of others -- a reflex is triggered as if even to say such things the lifeblood of English selfhood is carried to the precipice of destruction.

Even now, to question Churchill’s historical record triggers all manner of aggrieved reactions. To do so is perceived to be denigrating not only the man but the nation. Churchill, in this sense, remains a charged element in the civilization of the British. The aim of our book is to help the reader understand how and why.