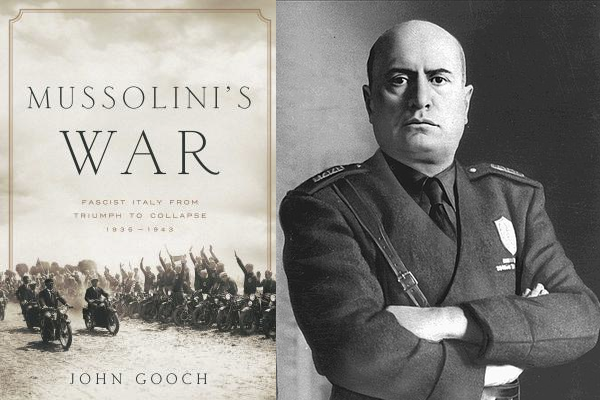

‘One Man, and One Man Alone’: Mussolini’s War

On October 3, 1935, Mussolini sent his armies into Abyssinia. Fascist Italy was now at war, and would be so more or less continuously for the next eight years; first Abyssinia, then Spain, then France, North Africa, the Balkans and finally Russia. Gradually, inexorably, defeat and disaster became the order of the day. Finally, on 25 July 1943, as the Fascist house of cards collapsed, Mussolini was unseated. Over the next forty-five days, the conservative elements around the king extricated themselves from Fascist Italy’s alliance with Nazi Germany and changed sides, abandoning their men to the new enemy. Several thousand soldiers were shot by the Germans, more went into prisoner-of-war camps, and more again went over to their one-time enemies and fought alongside Greek and Yugoslav partisans. Grandiose dreams of a new Roman Empire ended in catastrophe. How did this happen? And why did things go so badly wrong?

Fascist Italy may have looked strong and successful before the wars began – Mussolini had things to his credit, rebuilding a shattered state in the 1920s and pulling the country through the Great Depression – but when they did her economic weaknesses became increasingly apparent, and increasingly important. In his speeches, the Duce made great play with manpower, boasting on the eve of the Second World War that he could put eight million men in the field (he couldn’t). But Italy had none of the industrial and economic resources that she needed to keep her soldiers in the field, her ships at sea, and her planes in the skies: no coal, no oil (though ironically she was sitting on massive reserves in Libya), no iron ore, no metals like zinc and manganese. Her industrial sector was small, concentrated in northern Italy (which would make it vulnerable to Allied bombing), and heavily dependent on imports. The war Mussolini joined with great enthusiasm was a capital-intensive war. When she entered it in the summer of 1940, Italy was, in the words of one of Mussolini’s chief advisers, ‘like a bath with the plug pulled out and the taps turned off’.

None of this was unknown to Mussolini. Sheaves of economic data crossed his desk before the war and during it – and he simply ignored the numbers or downplayed their significance. The hard facts of economics were brushed aside in favor of will power, which Mussolini valued above everything else. Italy was now in the hands of a man who had neither the experience – he had been a corporal for a couple of years in the Great War before being hospitalized and had not taken part in any big battles – nor the ability to run the war. Advice and counsel might have helped, but Mussolini had no time for that. Massive personality defects ruled out listening to other people. Narcissistic to a degree, Mussolini presented himself to his subordinates and to the public as all-knowing – he could reel off statistics about how many sheep and cows there were in the country – and all-wise. A master of the media of his day – newspapers and state-controlled radio – he ruled on the basis of intuition and extemporization.

Autocrats – and Mussolini was certainly a would-be autocrat, although because Italy still had a king his authority was not complete – may sit at the top of the pile, but they do not fight wars, or run countries, alone. In the 1930s Mussolini found generals who promised him quick, fast-moving wars fought with lightly-motorized and mechanized troops. Between 1940 and 1943 they fought his wars for him – and lost them as they were out-gunned and overwhelmed by more powerful opponents. Airmen flew planes which had been state-of-the-art in the 1930s but by 1940 were fast becoming obsolescent thanks to poor leadership and direction, while their overlords quarrelled with sailors who demanded more air support as their battleships slowly ran out of fuel. Long-standing inter-service jealousies played out alongside budget rivalry as the men around Mussolini manoeuvred for their boss’s favor. Absent collective analysis and advice, misdirection at the top went hand-in-hand with mismanagement lower down.

Just as there was no real order to Mussolini’s direction of the national war effort, so there was no ordered thought behind the strategic decisions he made. Italians fought in the Mediterranean, North and East Africa, the Balkans and Russia, spreading their limited strength and magnifying their structural weaknesses, because Mussolini sent them there. He had his reasons – no dictator, would-be or actual, is simply a mad man acting without logic – and his own way of reasoning. Every campaign had a rationale – colonial expansion in Abyssinia, great power status in the Mediterranean and North Africa, ideology in Spain and Russia, regional dominance in the Balkans. A kaleidoscopic programme was shaped by opportunism and by rivalry: Mussolini acted on the spur of the moment, always sensitive to the need to be seen as Hitler’s equal. Rarely did anyone ever try to talk him out of a chosen course, and when they did so they failed. You couldn’t reason with him.

When Mussolini took Italy into the Second World War on June 10, 1940, the short-term circumstances were in his favor and the long-term odds were against him. Then, complete failure was perhaps not yet inevitable – though once the United States entered the war on December 7, 1941 it surely was. En route to defeat, Mussolini made bad choices, disregarded warnings that his military machine was not up to the demands he was making of it, and turned a blind eye to economic realities. Many of the failures and setbacks were his fault – though not all of them. Had he lived to write his memoirs, he would no doubt have railed against incompetent generals and inadequate subordinates. That would have been a smokescreen. The man who took his country to war, pouring scorn on Roosevelt and Churchill as he did so, was a lightweight when compared with the war leaders he had measured himself against.

The lesson of this history? Choose your leaders with great care, for they can do real and lasting damage.