Where In The World Are You? How My Great-Grandmother’s Letters Helped Me Locate My Great-Uncle after 78 Years

When did you last send a handwritten letter, or receive one? Can’t remember? Me neither, but there was a time, not that long ago, when the snap of the letterbox brought people rushing to see what had been delivered: reassuring words from a much-missed loved one, or the dreaded telegram bearing the very worst of news?

Much of what we know about the world wars comes from the letters and diaries of ordinary people caught up in those extraordinary events. Without these personal reflections, we wouldn’t have such an intimate knowledge of how war affected those who lived through it. Those like my great-grandmother, and great-uncle.

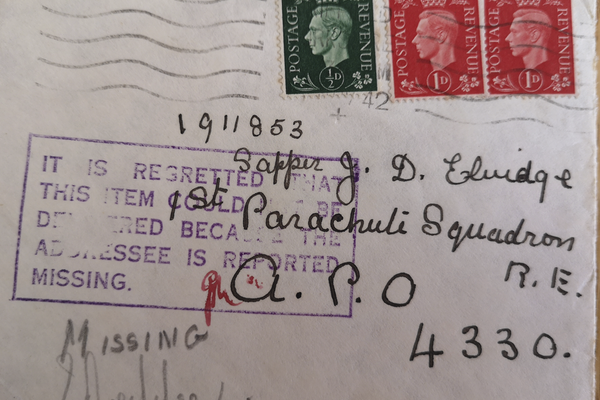

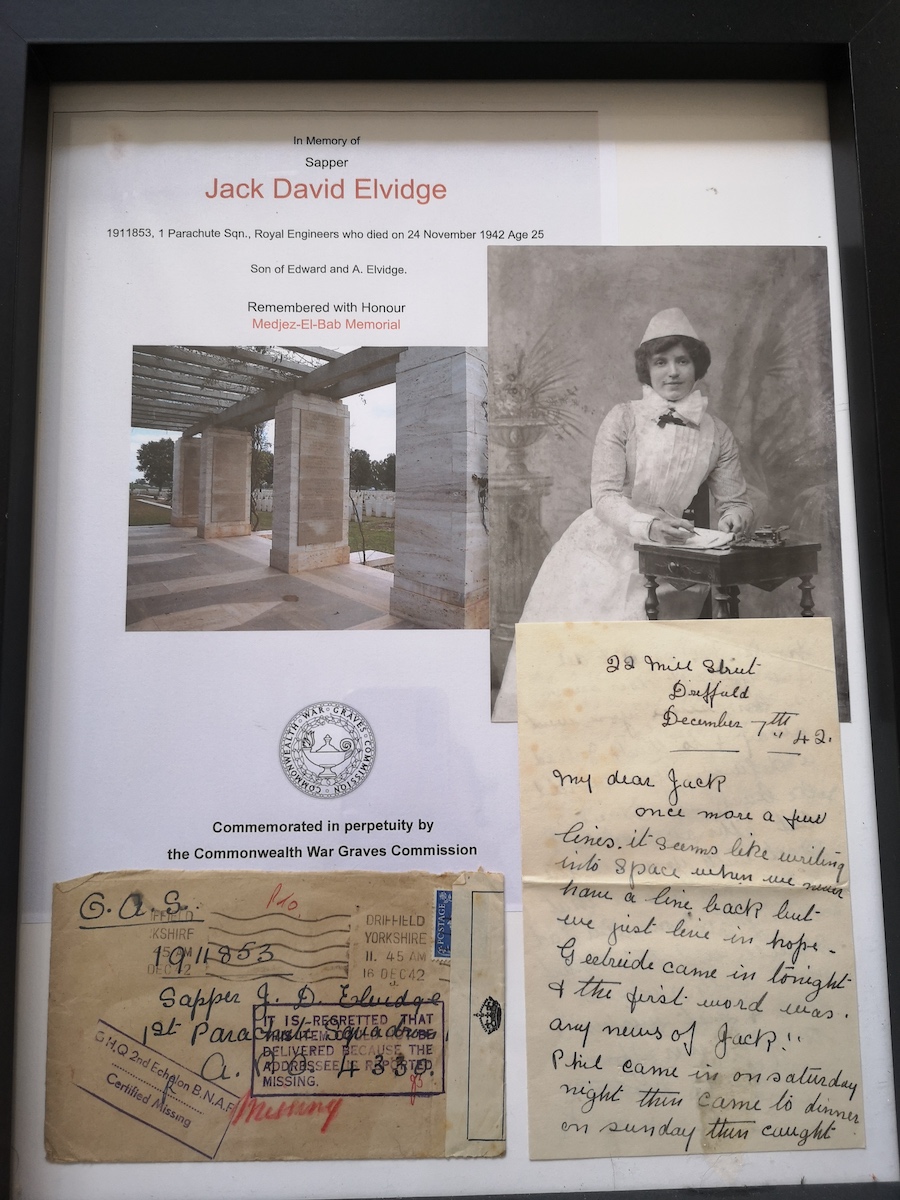

Between October and December 1942, my great-grandmother wrote a number of letters to her youngest son, Jack, who was reported as missing in action shortly after leaving home to fight for the British Army with his regiment from East Yorkshire. Jack, aged 25, was sadly never found and, heartbreakingly, my great-grandmother’s letters to him were all returned to her, marked simply, ‘To Mother’. Seven of these letters survive, and have been passed down through the family over the decades. In 2017, my father gave them to me.

Reading my great-grandmother’s unimaginable anguish, her desperate worry for Jack and her agony in not hearing from him, had a profound impact on me, and made me think about war in a different way. Her words made me realise that the pain of separation, of not hearing from loved ones for months, years, or ever again, wasn’t something that had happened to strangers in grainy black and white photographs, but had happened to my own family; to a mother, like me. Reading her letters inspired me to write a novel about the experience of ordinary people caught up in the war, and cut off from their loved ones, and soon after being given the letters, the right story found me: a story of the war in the Pacific; a story of resilient women and resourceful children; a story from a distant corner of that terrible war.

I first learned about the events that inspired When We Were Young & Brave in a podcast. The episode began as an amusing anecdote about waylaid Girl Scout cookies, but went on to reveal the remarkable true events surrounding a group of schoolchildren and their teachers who were taken to a Japanese internment camp in China, following the bombing of Pearl Harbor in December 1941. The children’s parents were mostly British, American and European missionaries and diplomats, and their lives, up to that point, had been one of great privilege. Many of the children were part of the school’s Girl Guides unit, and the principles of girl guiding, the routine of patrol meetings, the practical skills learned, and a willingness to Lend a Hand and Be Prepared, became increasingly important in helping them, and their teachers, endure their ordeal over the next five years. The account stirred fond memories of my own years as a Brownie, and of the BBC drama Tenko, and the Ingrid Berman movie, The Inn of the Sixth Happiness, based on the life of missionary Gladys Aylward.

I was intrigued, not only because World War II was an event I wanted to write about, but also because girl guides, schoolchildren and war simply didn’t belong together. I wanted to understand how it had happened, how the children and their teachers had coped in the circumstances they found themselves in so far from home, and how the experience, especially the prolonged separation from their family, had affected those children in later life. What I hadn’t expected to discover during my research was a story not only of unimaginable hardship, but of extraordinary hope, friendship, community and kindness as the children and their teachers adapted to the rapidly changing circumstances they found themselves in.

As a historical novelist, I spend a lot of time walking in the shoes of those who have lived through world-changing events, so it felt very fitting to finish editing When We Were Young & Brave during lockdown in March, at the start of our own world-changing event. Now, more than ever, it seems to me that the past is not a foreign country where people do things differently, but is a reassuringly familiar place, one from which we can draw comfort, one from which we can learn. Disaster and tragedy are often where we find our strongest bonds, and as we find ourselves separated from family and distanced from loved ones, stories of community and shared hope are, arguably, more important than ever.

In February this year, with the help of the War Graves Commission website, I located my great-uncle Jack. The family had always believed he was lost in France, but he wasn’t. He was in North Africa, in Tunisia, so very far away from his rural Yorkshire home. His final resting place is marked with a memorial plaque, noting his age and the date of his death. He died on the day great-grandma wrote her final letter to him.

Dec 27, 1942

My dear Jack, Where in the world are you? I keep writing and still no news of you. We are all ears at news time but seldom glean any news about your special team. How did you spend Christmas? We are all thinking of you … Everybody here has victory on their lips now, but I keep on looking for you. It does seem such long months since you went away.

Before my grandma passed away in May (after reaching her 100th birthday), we were able to tell her we’d found her brother’s final resting place, and show her the photograph of his memorial plaque. It gave her great comfort. Without my great-grandmother’s letters we would never have known how to find Jack, and I would never have understood how deeply the war had affected my family.

How incredible that the words of a mother to her son, written nearly seventy-five years ago, still evoke such powerful emotions. I now look at the faces in old family photographs with a renewed sense of connection, sadness, and above all else, a profound sense that the past is not so different, or far away, after all.