How Hudson Stuck's Ascent of Denali Boosted Recognition of Indigenous Alaskans

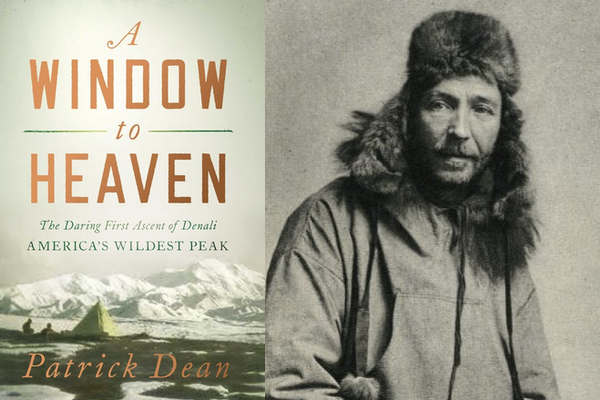

This past October marked the 100th anniversary of the death of a unique figure in American history. Hudson Stuck was an Episcopal priest, missionary, author, and explorer who organized the first party to reach the summit of Alaska’s Denali, in 1913.

But Stuck’s legacy reaches far beyond the list of mountaineering firsts. In his life and deeds, he represents an admirable American type: someone who embraced challenges, loved the wilderness, and strove to make life better for all. Wherever he was, Stuck used his position and influence to champion the rights of those less privileged.

Stuck himself was an immigrant. He left London in 1885 with a friend, flipping a coin that determined Texas as their choice over Australia. After riding the range and teaching school, Stuck was offered a scholarship to study theology at the University of the South, in the green mountains of Tennessee. The newly-minted priest returned to Texas as the Dean of St. Matthew’s Cathedral in Dallas.

There Stuck began his life’s work of improving, as he put it, “habits and character and mode of life.” In Dallas he founded a boys’ school and a night school for adult mill workers. Then Stuck took on the establishment, leading the successful fight for the first child-labor laws in Texas in 1902 against staunch opposition. “I am sorry,” he said, “for a life in which there is no usefulness to others.”

Wanderlust, as much as service, guided Stuck’s life. He had “a keen interest,” he wrote, “in what every new turn of a trail shall bring, every new bend of a river.” A childhood spent reading his uncle’s leather-bound tales of polar exploration left him yearning to experience wild places. He explored the Colorado Rockies, Yellowstone, and the Grand Canyon. His desire would drive him to eventually abandon the comforts of Dallas for the Far North—Alaska.

In 1904 Stuck became Archdeacon of Alaska and the Yukon, with responsibility for thousands of square miles in the vast interior of the territory. He quickly earned a reputation for getting things done, opening a hospital, a church, and a library in the new gold-mining town of Fairbanks. That winter he began the first of his yearly travels to visit his mission churches, which he recorded in his book Ten Thousand Miles with a Dog Sled, now considered an Alaskan classic.

By now Stuck was well-versed in mountaineering history and literature, and was well aware of the significance of the mountain which the white settlers and miners had begun calling Mount McKinley, after the American president. “How my heart burns within me whenever I get view of this great monarch of the North!” he wrote, and dreamed of the chance to add his name to the annals of great climbing feats.

In 1913 that opportunity came. Recruiting three others, plus two young Native boys as assistants, the party left Tanana on March 17, dogsledding to the base of the great mountain. Harry Karstens, a tough, experienced miner, dogsledder, and hunting guide, was Stuck’s co-leader of the expedition. Walter Harper, twenty-one, half-Alaska Native, and Robert Tatum, a young Tennessean studying for the priesthood, completed the party.

With Karstens and Harper leading the way, the group spent a month on the mountain. Dressed in layers of wool and furs, with lynx mittens and primitive crampons on their mocassins, they crossed the Muldrow Glacier, with its treacherous crevasses and blowing subzero winds. On June 7, 1913, it was Harper, fittingly, who was the first to stand at the highest point in North America. The group said prayers, and erected a cross and an American flag. Tatum wrote that the view from the top was like “a window to heaven.”

Hudson Stuck had achieved his goal. But beyond personal acclaim, the summit had a deeper purpose, in line with his greater life’s mission. In Alaska, as in Texas, Stuck strived to be of service. For him, the Native people deserved better than they had received from the white Gold Rushers who had overrun their ancestral land. “White men come and go, but the natives remain,” Stuck was known to argue. “So far as the interior is concerned our permanent work...is amongst the natives.” Unlike many missionaries, Stuck believed it was important that Natives be encouraged to sustain “their special cultures and their special tongues.” And he was unafraid of the hostility of those white Alaskans who abused the Alaska Native population. Stuck welcomed some whites’ enmity with his passionate harangues against the illicit whiskey trade “with which white men of the baser sort” attempted to corrupt Native women.

Stuck traveled throughout the United States speaking on behalf of the work in Alaska. In 1909, he went to the White House and shared his views with President Theodore Roosevelt. A decade later he was back in Washington, testifying in Congress that salmon-canning operations on the Yukon River were depriving Natives of their centuries-old ways of subsistence.

So for Stuck, the fame which accompanied the Denali expedition could be leveraged to argue for his causes — among them, his firm belief that the mountain should be known by its native name — Denali, “the Tall One.” His devotion to Alaska Natives earned him the Gwich’in name Ginkhii Choo, “Big Preacher.” In four books and countless articles and speeches, he described the beauty of the land and people he served, and argued passionately on their behalf.

On October 11, 1920, the sad telegram traveled through the winter dark from Fort Yukon, Alaska: “He is on the long trail now.” The trail Hudson Stuck had left, however, led directly to the official renaming, a century later, of the peak with which he is forever linked.

On August 28, 2015, Sally Jewell, Interior Secretary in the Obama administration, officially restored the name “Denali” to the peak. In her secretarial order, Jewell noted that “This name change recognizes the sacred status of Denali to many Alaska Natives.” The act was a delayed but fitting answer to Hudson Stuck’s plea almost a century before, in the preface to his book The Ascent of Denali, for that which was “…forefront in the author’s heart and desire…the restoration to the greatest mountain in North America of its immemorial native name.”