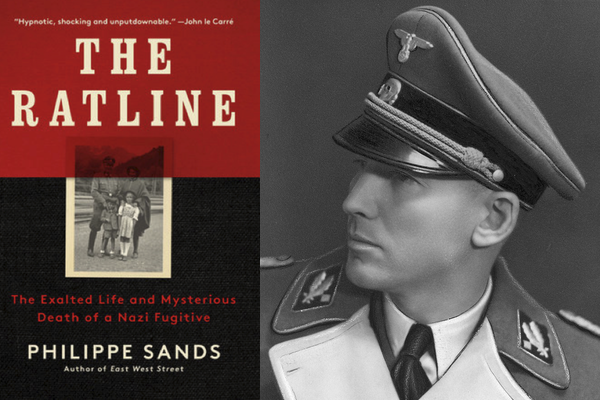

Review – The Ratline: The Exalted Life and Mysterious Death of a Nazi Fugitive by Philippe Sands

In August 1942, SS Major Otto Wachter was feeling frustrated. He was working long hours, setting up a concentration camps in German-occupied Ukraine, but he couldn’t find anyone to perform maintenance work at his headquarters in Lemburg. In a letter to his wife, Charlotte, he complained “the Jews are being deported in increasing numbers and it is hard to get powder for the tennis courts.”

The brutality and callousness of this Nazi officer, an Austrian lawyer, is on full display in The Ratline, the new book by Philippe Sands, which follows Wachter’s wartime career and mysterious death in 1949. Wachter, who indicted after the war for the murder of 400,000 Jews in western Ukraine, regularly boasted about his accomplishments to his wife. Charlotte, in turn, complained about his prolonged absences, while redecorating her new home with artworks and household goods looted from Jewish families and Polish museums.

The Ratline is based in part on several thousand letters exchanged between Otto and Charlotte, and the doomed love story between the ambitious SS major and his lonely wife is one of the running themes of the book. These letters and thousands of other documents and photos are part of the Wachter family archive now in the hands of Otto’s son Horst (born 1939).

The book unfolds as a gripping detective story as Sands, a human rights lawyer based in London, combs through the family’s archive and travels to Washington D.C. and Poland to uncover long-closed war crimes investigations from 1945-49.

The narrative takes an added twist with the perplexing response of the son, Horst Wachter, an elderly man now living in a refurbished castle in northern Austria. After Sands first meets with him in 2012, he gradually wins the trust of Horst, who slowly releases more and more of the family’s copious archives.

Horst even agrees to having a team from the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum come to his home. Equipped with high-speed scanning equipment, the museum digitized 9,000 documents and photographs (they can be found online at the museum’s Otto Wachter archive).

Despite the mounting evidence that his father directly ordered the extermination of hundreds of thousands of Jews, Horst insists that his father was innocent of war crimes. Horst makes various excuses for his father, first stating that Otto was “trying to act humanely” in Cracow. Later, when confronted with memos detailing the liquidation of thousands of Jews, Horst insists that his father didn’t “want” to organize the killings, but was “ordered” to do so by a Nazi judge in Germany.

Towards the end of the book, there is a chilling series of photographs showing Otto Wachter directing a group of SS soldiers in the execution of two dozen Polish hostages. When the author presents the photographs to Horst, the son is momentarily stunned, but insists that his father “wasn’t happy about shooting hostages.”

Horst’s cooperation extends to appearing in a 2015 film, What Our Fathers Did: A Nazi Legacy, which features Philippe Sands in a series of conversations with him and Niklas Frank, the son of Hans Frank, the Nazi governor of Poland, who was found guilty at the Nuremberg Trials and hanged in 1946. In the film, Horst defends his father’s actions, maintaining he was trying to be humane. Niklas Frank, on the other hand, denounces his father and agrees that he deserved to be executed for his crimes (the film is available on streaming services).

Death in Rome

While Otto Wachter’s wartime career is well documented, his public life ends in May 1945 with the collapse of the Nazi regime. He went underground, acquiring a series of different identities, living in the mountains of southern Austria, supplied with food and clothing by his wife. By 1949, Wachter sensed that Allied investigators were closing in. He was on a watch list of Nazi fugitives and worried he would soon be spotted, caught and put on trial. He made an arduous trek over the Alps into Italy, where he spent the last six months of his life living in a monastery controlled by a pro-Nazi Catholic Bishop, Alois Hudal. Although several Nazi fugitives (e.g., Adolf Eichmann) were able to escape from Italy to South America, Wachter was either unable or unwilling to obtain the papers required to get past port officials and successfully emigrate. He dallied in Rome, enjoying the historic city and even getting a part as an extra in an Italian film.

Otto Wachter died suddenly from a mysterious illness in a Catholic hospital in July 1949. Unable to communicate directly with his wife, he died alone and was buried in a Rome cemetery. Charlotte later exhumed his body and had it reburied near her home in central Austria.

The book’s title, The Ratline, refers to the loose network of ex-Nazis living in Austria and Germany, who worked with a rogue element of the Catholic Church to provide housing and false identity papers to Nazi war criminals fleeing Allied investigators.

In the 1974 Hollywood film The Odessa File, starring Jon Voight, the ratline is portrayed as a centrally operated, well financed operation enabling hundreds of Nazi fugitives to quickly gain new identities and escape justice.

But Sands’ book exposes this to be a Hollywood fantasy. In fact, the ratline was a poorly coordinated, shoestring operation, dependent upon a small group of sympathetic German businessmen and Catholic priests. The Ratline also gives glimpses into the secret operations of the Army’s Counter Intelligence Corps, the predecessor to the CIA, which screened many fugitive Nazis and recruited a select few to spy on Communists in Eastern Europe.

The Banality of Evil

In 1963, philosopher Hannah Arendt published Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, which was based on her attendance at Eichmann’s trial in Israel for the mass murder of Europe’s Jews.

Arendt described the “manifest shallowness” of Eichmann. She asserted that he acted “thoughtlessly” and that his crimes were committed “under circumstances that made it impossible for him to know or feel that he was doing wrong.”

Arendt said “The deeds were monstrous, but the doer, at least the one now on trial, was quite ordinary, commonplace and neither demonic nor monstrous.”

Arendt only attended the first two days of the Eichmann trial, and many subsequent Holocaust historians have disputed her conclusions. For example, Deborah Lipstadt noted that Arendt failed to consider much of the documentation released by the Israeli government. She also pointed out that the senior Nazis were quite aware of their guilt because, as defeat loomed, they feverishly tried to destroy evidence of their crimes.

In The Ratline, we see that Otto Wachter was hardly a banal or thoughtless individual. A highly educated man from an affluent family, he was a successful lawyer in Vienna before fleeing to Nazi Germany after the failed putsch in 1934. Wachter was a zealous anti-Semite and firm believer in Nazi ideology. He was given substantial authority to carry-out mass extermination in the captured territories and he acted with speed and efficiency, directly supervising mass killings when necessary.

Although The Ratline can be enjoyed as an absorbing detective story, it contains important lessons for 21st century readers. Tzvetan Todorov, a Paris-based Holocaust historian, wrote “Understanding evil is not to justify it, but the means of preventing it from occurring again.”

Although the Nazi regime was crushed militarily in 1945, the poison of anti-Semitism and the attraction to fascist dogma remain present to this day. They can be found today in Germany’s far-right, AfD Party and in some of America’s home-grown militia groups.

The Ratline gives readers a look a chilling look at the day-by-day actions of a top Nazi and the troubled legacy his family is still struggling with.