Pamela, Randolph and Winston: The Wartime Discord of the Churchills

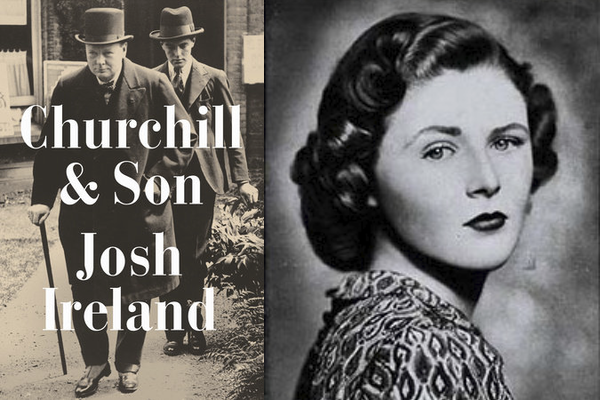

Pamela Digby, photographed in 1938, before her brief courtship and tumultuous marriage (1939-1945) with Randolph Churchill.

In the spring of 1941, Averell Harriman, Roosevelt’s special envoy to Britain, started an affair. That both he and the woman in question were married was not a huge problem; there were different rules in wartime. What was more complicated was the identity of the woman’s husband: Randolph Churchill, the British prime minister’s adored, spoiled, turbulent son.

Randolph had started the Second World War desperate for two things. He wanted to be wherever the fighting was fiercest, and was anxious to find a wife who would bear his child. Both were ways of pleasing his father, who placed an outsized premium on physical bravery, and was obsessed with the idea of building a powerful political dynasty. Randolph, he felt, had a duty to make sure the line was continued.

Randolph’s first ambition was stymied by the artificial calm that followed Hitler’s invasion of Poland, as well as his father’s reluctance to get him reposted. He was more successful in achieving the second. In the course of a fortnight he proposed to, and was rejected by, eight women. Then he met Pamela Digby.

Pamela had wide, deep-blue eyes, pink flushed cheeks and auburn hair streaked with a patch of white. Some saw her as “a red headed bouncing little thing regarded as a joke by her contemporaries,” but beneath the plumpness and a forced air of jollity was an adamantine desire to escape her dull, provincial life in Dorset.

Winston embraced her immediately. Pamela was soon an essential part of the Churchill family, especially once Winston became prime minister and they moved to Downing Street. She had an uncanny instinct for sensing what people needed, and then giving it to them almost before they had realized themselves. She was a source of support for an embattled Winston, and a much-needed confidante for his wife, the lonely Clementine. In October 1940 she gave birth to a boy, named, inevitably, Winston.

The only problem was her husband. Randolph was charming, clever, generous and funny. Most of the time. He was also rude, arrogant and incapable of understanding why marriage should stop him sleeping with other women. All of these qualities were exacerbated when he drank, which he did uncontrollably.

Bills and arguments mounted up. When Randolph behaved appallingly, or ran up debts he couldn’t cover, it was to his parents that Pamela ran for help. They, increasingly, took her side, which was another source of friction in an already fraught web of relationships.

It was after Randolph finally got his posting abroad that the problems really began. In January, 1941 his Commando unit set sail for Egypt. Before their ship had even docked on the other side of the Atlantic he’d lost more at the gaming table than he could possibly pay back. Once Pamela had fixed the financial disaster her wayward husband had forced upon her, she deftly, single-mindedly, began to fashion a new, independent life for herself. Before the end of spring she had started sleeping with Harriman.

Randolph was incandescent when he discovered his wife’s infidelity. This was largely because he was convinced that his father had at the very least tolerated, and at worst actually encouraged, an affair that was being conducted beneath his nose. After all, the situation presented a clear political advantage to Winston. And so although Pamela did not create the tensions that run between father and son – they had a long history of their own – her actions brought matters to a head.

Winston and Randolph’s bond had always had an almost romantic intensity. Winston was obsessed with his son, claiming that he would not be able to continue leading the country if anything were to happen to him; Randolph was devoted to his father. They had spent the last decade living in each other’s pockets: drinking, plotting, gambling, talking and quarrelling. But this closeness masked some profound difficulties.

Throughout his life Randolph had struggled to find a way of marrying the outsized expectations Winston had thrust onto his shoulders with the need to provide his father with the asphyxiating loyalty he demanded. Every time Randolph tried to fashion an opportunity for himself, or attempted to assert an independent position, he found himself accused of sabotage. He had been Winston’s most passionate defender during his time in the wilderness, an unfailing source of affection and reassurance. And yet when Winston formed his government in 1940, there was no place for Randolph. All of this had lain under the surface for years, now it erupted.

Volatile, unable to control their emotions, the two men launched into rows that frightened anybody who witnessed them. Winston became so angry that Clementine feared he would have a heart attack; Randolph stormed out of rooms in tears, swearing that he would never see his father again.

Although a fragile peace was restored, it could not last. Randolph was unable to reconcile the deep animal love he bore for his father with what he regarded as Winston’s treachery. Nor could he understand why his parents continued to show Pamela such open affection. Winston reacted violently to his son’s reproaches. Wrapped up in his own consuming sense of destiny, and unable to ever read what was going in anybody else’s heart, he did not see that he had done anything wrong. As Pamela moved serenely from one affair to the next, father and son fought, again and again, opening deeper and deeper wounds.

Randolph and Pamela’s divorce was confirmed in 1945. Randolph could survive this, but the damage to his relationship with Winston was irreparable. They would never recapture the intimacy they had enjoyed before the war. Randolph had married Pamela to make his father happy, and yet he only succeeded in alienating the man he loved more than anybody else on the planet.