The Scandalous Six Week Walk That Inspired D. H. Lawrence's Most Popular Novels (excerpt)

On August 5, 1912, Frieda von Richthofen, a thirty-three-year-old German aristocrat and married mother of three, awoke to the sound of rain. It was four thirty in the morning. Quivering strips of pearly light seeped through the sides of the shutters. She opened her eyes, dimly aware of her young lover strapping up their rucksacks and humming beneath his breath. At last she was about to embark on a real adventure, the sort of escapade she’d dreamt of for the last ten years. It had been a long, dry decade in which her emotionally restrained life in a comfortable suburban house on the edge of industrial Nottingham had almost driven her mad.

Her lover was the fledgling writer D. H. Lawrence, a penniless coal miner’s son whom she’d met four months earlier. The pair of them had been poring over maps and guidebooks for days, plotting a route that would take them through “the Bavarian uplands and foothills,” over the Austrian Tyrol, across the Jaufen Pass to Bolzano, and down to the vast lakes of Northern Italy.

Later, this six-week walk would become much mythologised as their “elopement.” But the evidence suggests this was less an elopement than a feverish bid for freedom and an inarticulate yearning for renewal. On the first misty, sodden step of that six-week walk, Frieda began the process of reinventing herself as a woman without children, scissoring herself free from the restrictions and responsibilities that accompanied being a mother in Edwardian England. Almost overnight she transformed herself from a fashionably dressed and hatted mother and manager of multiple household staff to someone else entirely: a woman who put comfort before fashion, who took responsibility for her own cooking and laundry, who swapped warm, soapy baths for ice-cold pools and the latest flushing lavatory for speedy squats among the bushes.

Frieda’s isolation was exaggerated by her choice of paramour. Lawrence spoke with a Derbyshire accent. He dressed in cheap clothes and came from a rough mining village. He was also six years younger than she was, at a time when women were expected to marry older men. To leave children, a comfortable home, and a successful husband broke every taboo. To leave them for a man like this was unthinkable.

In 1912, this was not how women behaved. Least of all mothers.

—

Frieda and Lawrence put on their matching Burberry raincoats. Frieda donned a straw hat with a red velvet ribbon round the brim. Lawrence wore a battered panama. They squeezed a spirit stove into a canvas rucksack, planning to cook their supper at the side of the road. They had twenty-three pounds between them, barely enough to reach Italy.

The pair chose a punishing route that would fully occupy them with its steep climbs and its perilous twists and turns. Neither of them had walked or climbed in mountains before, neither was a skilled orienteer, and neither was particularly fit. Lawrence found the mountains bleak and terrifying, seeing there the eternal wrangle between life and death. Later, he made full use of his Alpine terror in Women in Love, sending Gerald Crich to a lonely death in the barren glaciers of the Alps. Frieda, however, thought it was “all very wonderful.”

On this walk, the pair averaged ten miles a day, much of it uphill and strenuous, much of it cold, always with their packs on their backs. On some days they walked farther still. Only when the weather was particularly hostile did they allow themselves the luxury of catching a train to the next town.

Even as Frieda and Lawrence celebrated their new-found freedom—from their past lives and from the passionless provincialism of pious England—they were acutely aware of how hemmed in they were. Frieda’s presence had a profound effect on Lawrence, sparking a creative surge that resulted in dozens of short stories, poems, and essays, as well as his three acknowledged masterpieces: Sons and Lovers, The Rainbow, and Women in Love. But as he led Frieda farther and farther away from her previous life, he began to see how necessary she was to him. Not only for his happiness but for the continued blooming of his genius. Many of his poems are testimony to this feeling of necessity, a feeling that occasionally tips into a terrified dependency:

The burden of self-accomplishment!

The charge of fulfilment!

And God, that she is necessary!

Necessary, and I have no choice!

Frieda discovered that her new-found liberty was similarly compromised. She left her husband, children, and friends to discover her own mind, to be freely herself. But freedom is infinitely more complicated than simply casting off the things we believe are constraining us. Hurting others in the pursuit of freedom and self-determination brought its own struts and bars, its own weight of guilt. Frieda never shared the great weight of her guilt. She couldn’t. Lawrence wouldn’t allow it. His friends joined forces with him, insisting that she put up or shut up, that her role was to foster his genius. At any price.

—

After six weeks, Frieda and Lawrence arrived in Riva, then an Austrian garrison town on Lake Garda. Vigorous ascents over steep mountain passes in snow and icy winds followed by nights in lice-ridden Gasthäuser had left them looking like “two tramps with rucksacks.” Within days a trunk of cast-off clothes from Frieda’s glamorous younger sister had arrived, swiftly followed by an advance of fifty pounds for Sons and Lovers from Lawrence’s publisher. In a big feathered hat and a sequinned Paquin gown, an exuberantly overdressed Frieda and a shabbier Lawrence sauntered round the lake, celebrating their return to civilisation and rubbing shoulders with uniformed army officers and elegantly dressed women.

So why did Frieda devote less than twenty-five lines of her memoir to this pivotal time in her life? She writes in the same book: “I wanted to keep it secret, all to myself.”

This journey was so vivid and intense, so personal, that neither Frieda nor Lawrence wanted to enclose it or share it. When Lawrence fictionalized a version of it in Mr. Noon, he never sought publication (unusually for him as they invariably needed the money). Instead, he consigned it to a drawer. Nor, after his death, did Frieda try and have Mr. Noon published—despite publishing other writings Lawrence had chosen to keep private. Mr. Noon stayed unpublished until 1984.

—

Twenty months after their Alpine hike, and at his insistence, Frieda married an increasingly restive and cantankerous Lawrence, arguably exchanging one form of entrapment for another. It wasn’t until his death in 1930 that she became free to live as, and where, she wanted. In a bold attempt to finally assert her own identity she used the name “Frieda Lawrence geb. Freiin von Richthofen” on the opening page of her memoir. That, I suspect, was her definitive moment of freedom.

After Lawrence died, she lived in the same ranch (“wild and far away from everything”) in Taos, New Mexico, for much of her remaining twenty-six years. Here she cultivated a close group of friends, a surrogate for the family she’d sacrificed. And she walked. Her memoir is peppered with references to walking: “We were out of doors most of the day,” she says, on “long walks.” Her first outing with Lawrence, shortly after they met, had been “a long walk through the early spring woods and fields” of Derbyshire with her two young daughters. It was on this walk that she discovered she’d fallen in love with Lawrence. Later she wrote of “delicious female walks” with Katherine Mansfield, walks through Italian olive groves, walks into the jungles of Ceylon, walks along the Australian coast, walks through the canyons of New Mexico, or simply strolls among “the early almond blossoms pink and white, the asphodels, the wild narcissi and anemones.” Frieda walked in the countryside for the rest of her life.

But the pivotal walk of her life—the six-week walk she skirted in twenty-five lines—was the most significant. From here, Frieda emerged as herself, as the free woman she had always longed to be—dressing in scarlet pinafores and emerald stockings, swimming naked, making love en plein air, walking as she wished. She had also become the free woman Lawrence needed for his fiction. He made full use of her in his writing, continually remoulding her, most famously as Ursula in Women in Love, and Connie in Lady Chatterley’s Lover. His novels shaped history, but Frieda was the catalyst.

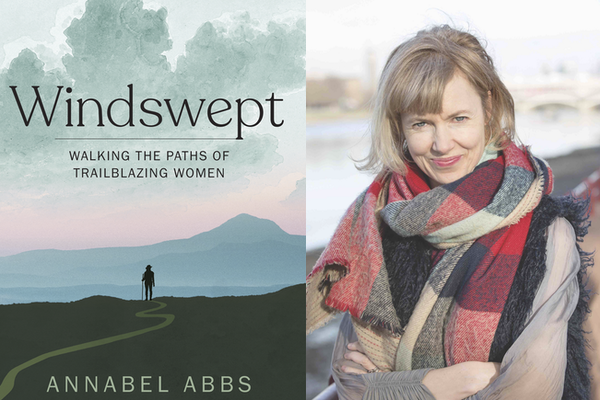

Excerpted from WINDSWEPT: Walking the Paths of Trailblazing Women by Annabel Abbs. Copyright (c) 2021 by Annabel Abbs. Published by Tin House.