Mussolini in Myth and Memory

In an unexpected explosion of publications, the bookshops of Europe are suddenly full of titles stressing the dangers of a new Fascism. It is not the fascism of Putin that causes concern; it is the threat posed to democratic institutions by what many call “democratic decline.” Populism, the advent of right-wing—even extreme right-wing—government in some countries, and the advent of “illiberal democracy” in others are all factors which have combined to make many feel they are living on the edge of a precipice. A further aspect of this crisis of democracy is that of a renewed fascination with dictators. Opinion polls in Russia put Stalin back among the leaders most missed, South Korea's Park Chung-hee has a growing fan club, and even the once-loathed Ceausescu is surrounded by nostalgia in Romania. This poses an unavoidable question: How can this be?

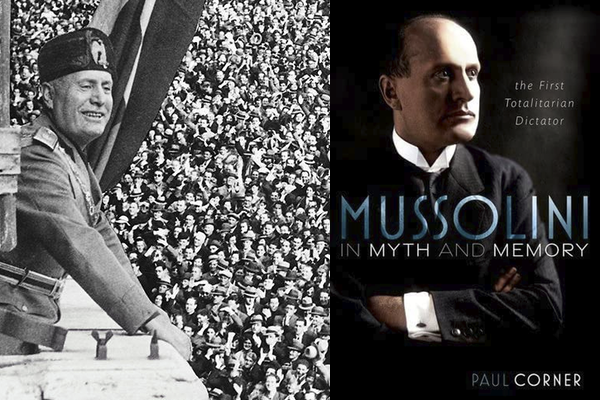

The myth of Mussolini, the strutting Italian dictator, is a useful starting point. In the current turmoil surrounding democratic institutions, analogies to the 1920s and the 1930s are common. Inevitably Hitler and Mussolini are in the foreground. But while Hitler, because of the Holocaust, remains almost the embodiment of evil, the Italian leader often enjoys very different press. Attitudes toward him within Italy are frequently ambivalent, if not unashamedly indulgent. It may be an exaggeration to say that Mussolini is back, but for many, the memory of the fascist leader is not that of a violent and cynical dictator, responsible for at least half a million Italian deaths, but that of the strong leader who—according to the popular phrase—did “many good things.” The myth of continual successes—a myth created by the fascists themselves—has been turned into a spurious “memory” of the fascist past. Only very recently, at the time of the commemoration of the centenary of Mussolini's March on Rome, around 4000 black-shirted admirers of the Duce merged on the small town of Predappio—his birthplace—in order to celebrate his memory.

This, and the recent election of a “post-fascist” leader as the first woman prime minister of Italy, is a reminder of what has been known for a long time, which is that Italy, unlike Germany, has never really come to terms with its fascist past. There is even physical evidence of this. Whereas in Germany Nazi monuments were torn down and others constructed in order to remind people of Nazi crimes, in Italy monuments glorifying the Duce are still there for all to see.

Why is this? What has happened to permit such a distortion of memory? How do myths replace reality? Clearly Mussolini has benefited from comparison with Hitler. He was, undoubtedly, the “lesser evil” – a fact that permitted prime minister Silvio Berlusconi to assert, ridiculously, that “Mussolini never killed anybody,” as if Stalin strangled people with his bare hands. Here the “lesser evil” has become no evil at all.

But current indulgence towards the fascist leader has other causes, some historical, some related to more immediate problems of political instability and economic insecurity. At the historical level, the way in which Italy emerged from the Second World War has great importance. Italians (very understandably) chose to forget Mussolini's alliance with Hitler and to emphasize instead the role played by the Italian Resistance movement in the defeat of the Nazi-fascists. It was an emphasis which suggested that Italians had been victims of Fascism. As victims, of course, there was no need for Italians to come to terms with the fascist past.

Even when historians began to question this reading of events—after all, Mussolini had been extremely popular among many Italians for more than twenty years—nothing changed. In a remarkable process of self-forgiveness, Italians remained convinced of their innocence. This process relied on a common Italian trope which assumes that Italians are intrinsically “good people.” Thus, the argument went, “if we were all fascists, and if we are all good people, then it follows that Fascism could not have been so bad.” Again Italians were off the hook. If, as victims of Fascism they bore no responsibility, as supporters of what was now cast as a benign dictatorship, they had nothing to explain. Germans might have a past that could never pass, but Italians had a past that presented no problems. The path was wide open to a distorted memory of dictatorship.

The media have played their part in this distortion. Television, in particular, has long shown images of the regime drawn from fascist propaganda. People view the regime through a lens provided by what is, in effect, the self-representation of Fascism. Predictably, this lens projects a world of one success after another, of marshlands drained, trains on time, healthy babies and smiling faces. Mussolini's attempt to make Italy great again is there for all to see. It all looks very convincing. The constant violence of the regime, effected in the early years by what was in fact a private militia, is airbrushed out of the picture. Corruption, illegality, the assumption of impunity before the law: these never merit comment. There is rare mention of the tens of thousands of Africans killed in the colonial massacres of the 1930s. Between fake news, amnesia and removal, the real picture of Italian Fascism can never emerge. On the contrary, the picture we form in our minds is comforting and reassuring.

Not all Italians are flocking to pay homage to the Duce in Predappio, of course. To suggest as much would be a gross exaggeration. Even so, the generalized indulgent attitudes towards Mussolini provide a classic case of historical memory being transformed into collective myth. And, in times of increased instability, the myth of the strong leader has evident attractions. As we have seen, even Stalin has his admirers nowadays. In the Italian case, the “Mussolini myth” has developed through a partisan reading of the past, determined by political choices of what was best said and best left unsaid, by a desire to construct a comforting view of the past, and by the more fundamental disposition on the part of many to believe what they want to believe, regardless, or in ignorance, of the facts. The appeal of the firm hand trumps rational discourse. In many respects the current myth of Mussolini—the benign dictator—represents a refusal to confront past errors, a preference for the head in the sand. It is ironic that this kind of retreat from politics reproduces the same kind of retreat made by many Italians in the 1930s. They took refuge in the fascist slogan—“Mussolini is always right”—and abandoned any kind of genuine political involvement with, as we now know, disastrous consequences.