America Fought Its Own Battle Over Books Before it Fought the Nazis

When United States servicemen stormed the beaches in Normandy, most of them had an essential item tucked into their breast pocket—not a weapon or food or other gear, but a lightweight paperback novel.

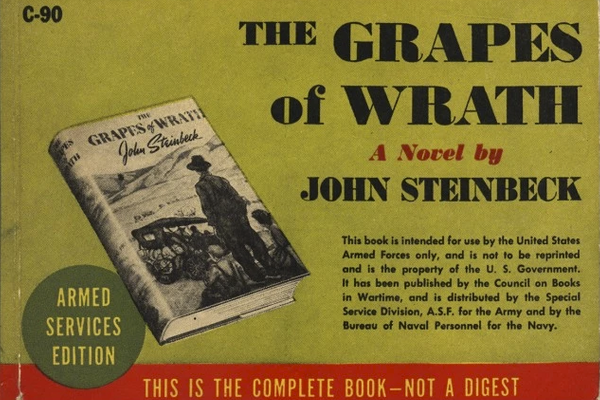

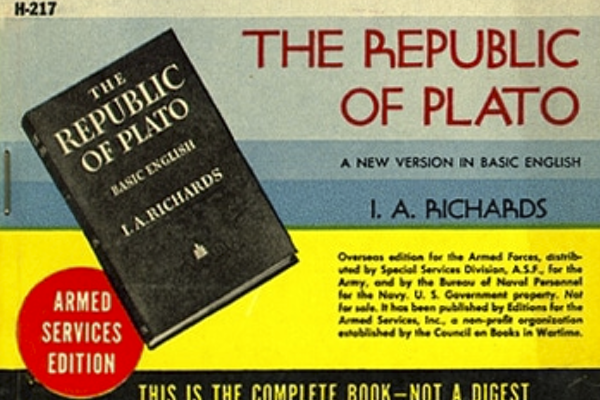

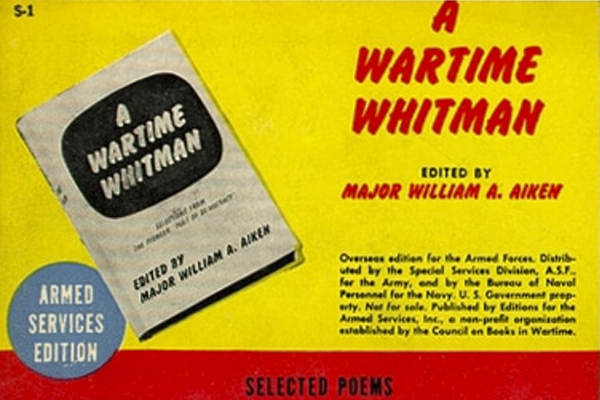

These weren’t just any books. These were Armed Services Editions, softcover versions of popular novels, classics, Westerns, mysteries and everything in between. Their dimensions were such that they fit perfectly in the soldiers’ uniform pockets and, while sturdy enough to withstand weather and repeated readings, could be ripped apart and shared between the men.

They became one of the Army’s most successful and popular morale boosters throughout World War II. Soldiers lined up to fight for the best books on delivery day, they read passages to each other in foxholes to relieve fear and boredom, and turned to them when they were at the far edge of their despair.

While the bold publishing experiment paid off ten-fold, the ASEs had a rocky road to existence. An Army Librarian named Raymond L. Trautman had a goal to get books into the hands of every soldier serving abroad. When the government called for Americans to donate to the cause, the Army received primarily hardcovers. Those were fine for U.S. bases but they weren’t deployment-friendly.

After a few fits and starts, Trautman came up with the idea of the ASEs with the help of a graphic artist and the Council on Books in Wartime, a nonprofit organization made up of publishers, librarians, book sellers and other industry professionals. For the Council, the ASE partnership was the perfect way to fulfill its core mission of using books as “weapons in the war of ideas” that the Nazis had kicked off long before they invaded Poland.

In fact, the Nazis had honed that particular weapon to near perfection. The infamous book burnings in Berlin on May 10, 1933 were just the tip of the iceberg. From the early days of the party, the leaders understood the unique power of books to shape opinions, feed anxiety, and set a cultural landscape that would support their fear-based, bigoted policies. When they burned books by particular writers, they were making it clear what kind of voices were welcome in their Germany. This served the purpose of clarifying exactly who the Nazis’ scapegoats were while at the same time creating a strong sense of party unity. With the physical act of burning their own personal libraries, Germans were making a pledge to the Nazis and their ideology.

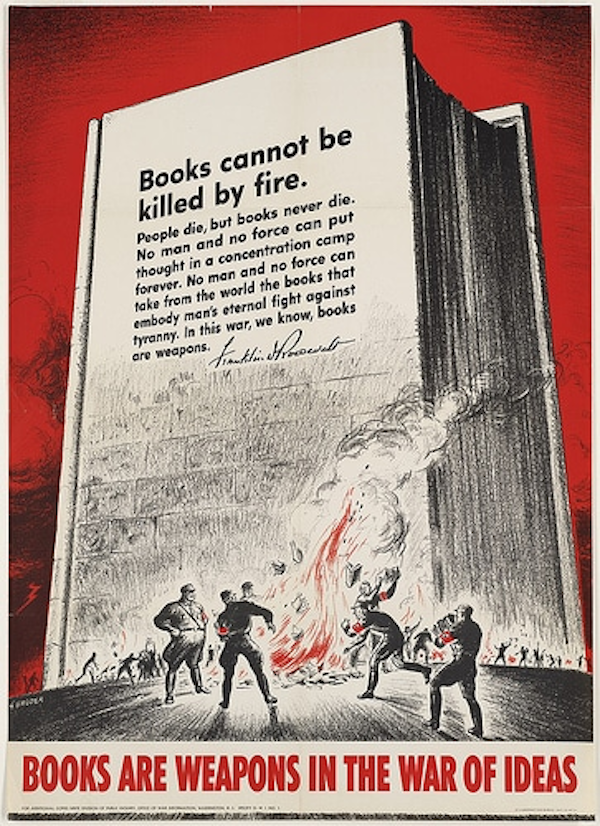

In war propaganda, where ideas have to be both bold and easy to communicate, there was no clearer line to be drawn than this: America was the land of the free and Germany was the land where fascists burned books.

President Roosevelt himself amplified this message. “Books cannot be killed by fire. People die, but books never die,” he said, the words later splashed over popular propaganda posters. “No man and no force can take from the world the books that embody man’s eternal fight against tyranny. In this war, we know, books are weapons.”

But, as propaganda so often does, that flattens the actual state of affairs in the United States at the time. The Armed Services Editions themselves—wildly popular and supported by both General Eisenhower and President Roosevelt—became a target of a powerful senator’s censorship efforts. Senator Robert Taft of Ohio, who had his eye on the White House, attached an amendment to a must-pass soldiers’ voting bill that severely limited what books could be part of the ASE program—essentially banning books selected by an organization whose main purpose was to use books to fight those who wanted to ban them.

One Council member claimed that that censorship bill was so overreaching that there’d be nothing left to send the boys besides the Bobbsey Twins.

While that was happening, the book Strange Fruit, a novel about an interracial relationship, was banned in Boston and Detroit, as well as banned from being sent through the mail. According to Molly Guptill Manning’s When Books Went to War, the cities weren’t bluffing. One shop-owner in Boston ignored the legislation and was arrested for selling literature that would corrupt the morals of the youth.

The two incidents caused the Council on Books in Wartime to come out strongly against the anti-American censorship efforts. When appealing to Sen. Taft himself didn’t work, the Council members went directly to the people, via editorials and opinion pieces, beseeching the public not to put up with this “Goebbels purge.”

The Council members eventually prevailed against Taft and were allowed to continue sending any book they deemed worthwhile to soldiers. But the incidents serve as a reminder that bans can be extremely unpopular, taboo, and reviled—and yet still get passed.

That sentiment has carried on today, where the vast majority of Americans oppose book banning. Poll after poll shows that the practice isn’t something most Americans want. Still, in recent years there have been a record number of challenges against books, especially novels in school libraries.

And that’s not the only pattern that has been re-emerging.

The Nazis didn’t only burn books by Jewish writers. In the days before the bonfires, they raided an institute in Berlin that was ahead of its time in research on gender, sexuality and women’s health. The students who organized the book burnings destroyed years of ground-breaking LGBTQ research and then carried a statue of Magnus Hirschfeld, the institute’s founder, through the streets as a trophy.

Today, the top reason for a book to be challenged or removed from a school library, according to PEN America, is because it has LGBTQ characters or content. That reason is followed closely by books that have a character who is not white. The number drops dramatically after that, from 41 and 40 percent to 22 percent for sexual content.

We have long accepted that the books we read reflect what we want our national identity to be. That was true when the Nazis were burning Albert Einstein’s work and it was true when Roosevelt intervened to lift the post-office ban on Strange Fruit. It was true when the Nazis decided to eradicate Jewish voices, queer voices, and the voices of their political opponents from the German culture. And it was true when Eisenhower made sure each of his men, who were headed toward probable (if not quite certain) death, had a book to keep him company in his last hours.

If past is prologue, it’s now more important than ever to read that particular chapter. To understand that books are weapons—but weapons that can be used with both good and evil intent. To lift up, to support communities, to create connections to people so unlike ourselves; or to erase, suppress and ostracize minority voices. Their power to create empathy is unmatched, but so is their power to act as a symbol for silence.

Pete Hautman, writer of young adult fiction, says it best: “Yes, books are dangerous. They should be dangerous—they contain ideas.”

What to do about that fact has defined our history—has defined us—ever since there have been books and there has been fire.