Stronger Global Governance is the Only Way to a World Free of Nuclear Weapons

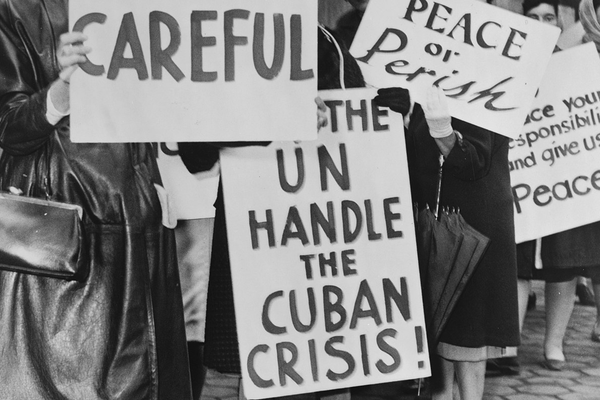

Some of the 800 members of Women Strike for Peace who marched at United Nations headquarters in Manhattan to demand UN mediation of the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis

It should come as no surprise that the world is currently facing an existential nuclear danger. In fact, it has been caught up in that danger since 1945, when atomic bombs were used to annihilate the populations of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Today, however, the danger of a nuclear holocaust is probably greater than in the past. There are now nine nuclear powers―the United States, Russia, Britain, France, China, Israel, India, Pakistan, and North Korea―and they are currently engaged in a new nuclear arms race, building ever more efficient weapons of mass destruction. The latest entry in their nuclear scramble, the hypersonic missile, travels at more than five times the speed of sound and is adept at evading missile defense systems.

Furthermore, these nuclear-armed powers engage in military confrontations with one another―Russia with the United States, Britain, and France over the fate of Ukraine, India with Pakistan over territorial disputes, and China with the United States over control of Taiwan and the South China Sea―and on occasion issue public threats of nuclear war against other nuclear nations. In recent years, Vladimir Putin, Donald Trump, and Kim Jong-Un have also publicly threatened non-nuclear nations with nuclear destruction.

Little wonder that in January 2023 the editors of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists set the hands of their famous “Doomsday Clock” at 90 seconds before midnight, the most dangerous setting since its creation in 1946.

Until fairly recently this march to Armageddon was disrupted, for people around the world found nuclear war a very unappealing prospect. A massive nuclear disarmament campaign developed in many countries and, gradually, began to force governments to temper their nuclear ambitions. The results were banning nuclear testing, curbing nuclear proliferation, limiting development of some kinds of nuclear weapons, and fostering substantial nuclear disarmament. From the 1980s to today the number of nuclear weapons in the world sharply decreased, from 70,000 to roughly 13,000. And with nuclear weapons stigmatized, nuclear war was averted.

But successes in rolling back the nuclear menace undermined the popular struggle against it, while proponents of nuclear weapons seized the opportunity to reassert their priorities. Consequently, a new nuclear arms race gradually got underway.

Even so, a nuclear-free world remains possible. Although an inflamed nationalism and the excessive power of military contractors are likely to continue bolstering the drive to acquire, brandish, and use nuclear weapons, there is a route out of the world’s nuclear nightmare.

We can begin uncovering this route to a safer, saner world when we recognize that a great many people and governments cling to nuclear weapons because of their desire for national security. After all, it has been and remains a dangerous world, and for thousands of years nations (and before the existence of nations, rival territories) have protected themselves from aggression by wielding military might.

The United Nations, of course, was created in the aftermath of the vast devastation of World War II in the hope of providing international security. But, as history has demonstrated, it is not strong enough to do the job―largely because the “great powers,” fearing that significant power in the hands of the international organization would diminish their own influence in world affairs, have deliberately kept the world organization weak. Thus, for example, the UN Security Council, which is officially in charge of maintaining international security, is frequently blocked from taking action by a veto cast by one its five powerful, permanent members.

But what if global governance were strengthened to the extent that it could provide national security? What if the United Nations were transformed from a loose confederation of nations into a genuine federation of nations, enabled thereby to create binding international law, prevent international aggression, and guarantee treaty commitments, including commitments for nuclear disarmament?

Nuclear weapons, like other weapons of mass destruction, have emerged in the context of unrestrained international conflict. But with national security guaranteed, many policymakers and most people around the world would conclude that nuclear weapons, which they already knew were immensely dangerous, had also become unnecessary.

Aside from undermining the national security rationale for building and maintaining nuclear weapons, a stronger United Nations would have the legitimacy and power to ensure their abolition. No longer would nations be able to disregard international agreements they didn’t like. Instead, nuclear disarmament legislation, once adopted by the federation’s legislature, would be enforced by the federation. Under this legislation, the federation would presumably have the authority to inspect nuclear facilities, block the development of new nuclear weapons, and reduce and eliminate nuclear stockpiles.

The relative weakness of the current United Nations in enforcing nuclear disarmament is illustrated by the status of the UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. Voted for by 122 nations at a UN conference in 2017, the treaty bans producing, testing, acquiring, possessing, stockpiling, transferring, and using or threatening the use of nuclear weapons. Although the treaty officially went into force in 2021, it is only binding on nations that have decided to become parties to it. Thus far, that does not include any of the nuclear armed nations. As a result, the treaty currently has more moral than practical effect in securing nuclear disarmament.

If comparable legislation were adopted by a world federation, however, participating in a disarmament process would no longer be voluntary, for the legislation would be binding on all nations. Furthermore, the law’s universal applicability would not only lead to worldwide disarmament, but offset fears that nations complying with its provisions would one day be attacked by nations that refused to abide by it.

In this fashion, enhanced global governance could finally end the menace of worldwide nuclear annihilation that has haunted humanity since 1945. What remains to be determined is if nations are ready to unite in the interest of human survival.