Escaping Slavery in Washington Territory

When we think of the cruel legacy of slavery and the bloody Civil War that ended this vile institution, it’s unlikely that images of the verdant, sparsely populated Washington Territory soon come to mind. But settlers brought the seeds of the war with them, and issues of slavery, race, secession, and civil rights divided communities and loyalties in the Pacific Northwest.

When we think of the cruel legacy of slavery and the bloody Civil War that ended this vile institution, it’s unlikely that images of the verdant, sparsely populated Washington Territory soon come to mind. But settlers brought the seeds of the war with them, and issues of slavery, race, secession, and civil rights divided communities and loyalties in the Pacific Northwest.

Seattle public historian Dr. Lorraine McConaghy and co-author Judy Bentley uncover and detail a fascinating story of this era in Washington Territory in their new book Free Boy: A True Story of Slave and Master (University of Washington Press). Based on extensive research, they chronicle the odyssey of a young slave, Charles Mitchell, who escaped from slavery in Olympia to freedom in Victoria, Canada.

James Tilton, the surveyor-general for Washington Territory, “owned” Mitchell who was likely a wedding gift to the Tiltons. Tilton brought Mitchell along when he moved with his family from Indiana to Olympia in 1855.

While illuminating territorial and national history and the attitudes of the period, Free Boy recounts how, in 1860, a group of courageous free blacks arranged for the flight of 13-year-old Charles Mitchell aboard the steamer Eliza Anderson to freedom in the Crown Colony of Victoria.

Dr. Lorraine McConaghy is the public historian at the Museum of History and Industry in Seattle, who believes that “we study the past to make the present make sense, so that we can make better choices for the future.” In addition to her work with MOHAI, Dr. McConaghy teaches at the University of Washington and offers presentations in Humanities Washington's Inquiring Mind series. Her other books include Raise Hell and Sell Newspapers, Warship Under Sail, and New Land North of the Columbia. Her work has been honored by the Pacific Northwest Historians Guild, the American Association for State and Local History, the National Council on Public History, and the Oral History Association. She also is a recipient of the prestigious Robert Gray Medal from the Washington State Historical Society. She earned her doctorate at the University of Washington.

Dr. McConaghy also planned the Washington Territorial Civil War Read-In, an ambitious project of the Washington State Historical Society to recruit hundreds of citizens to research and document the Civil War era territorial experience from 1857 to 1871, an effort to uncover stories from the period -- like the Charles Mitchell escape -- that have been buried and forgotten. Readers will build a website hosted by WSHS.

Free Boy co-author, Judy Bentley, teaches at South Seattle Community College and is the author of Hiking Washington's History, along with fourteen books for young adults.

Dr. McConaghy recently discussed Free Boy and her eye-opening research on Washington Territory during the Civil War era.

* * * * *

Robin Lindley: How did you find the story of young Charles Mitchell’s escape from slavery in Washington Territory to freedom in Canada?

Dr. Lorraine McConaghy: In 2008, the Museum of History and Industry hosted a traveling exhibit from the Constitution Center in Philadelphia called “Lincoln, the Constitution and the Civil War.” My job as the museum’s public historian is to root a traveling show like that in the local experience so that it’s relevant to our visitors and hasn’t landed like an asteroid in our galleries, but makes sense regionally and locally.

I had been told all my life that there was no Civil War to talk about in Washington Territory, so I was not optimistic to find anything about it. But I thought I’d give it a try.

I thought if the settlers in the Territory got excited about anything, they’d get excited about the presidential election of 1860. Lincoln ran in a four-way race against John Breckinridge, Stephen Douglas, and John Bell. But Territorial settlers here couldn’t vote until 1889 when we became a state.

I was blown out of my chair when I read the Olympia Pioneer and Democrat on microfilm from September 1860 looking toward the election in November. It was very clear that people in Washington Territory had strong opinions on states’ rights and slavery. I was told so often that people didn’t -- that people came here to get away from the war, to plant orchards.

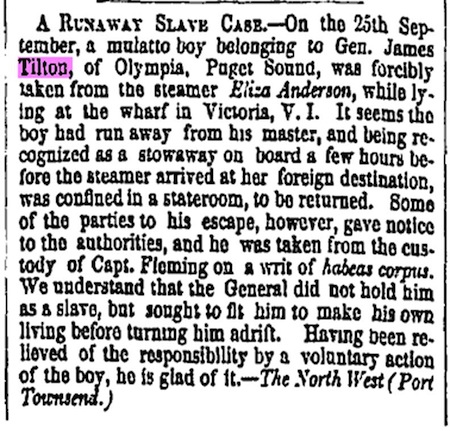

Anyway, I was reading along and saw a little article headlined “Fugitive Slave Case.” I thought they were reporting news from the east about the Underground Railroad in Ohio or New York. But it wasn’t. It was about a boy fleeing Olympia for Victoria. I couldn’t believe it. I’d never known that there was a slave or any slaves in Washington Territory, let alone one so young who had fled on this tiny Puget Sound Underground Railroad.

I sat bolt upright and said, “Everything I know is wrong.” No one had ever mentioned this to me. And no one had ever mentioned that there were advocates of slavery publishing their views in the newspaper. As I read, I found treasonous organizations in Washington Territory and many officers resigning their commissions in the Army and Navy and even the governorship of the territory to go south. It turned out this was a big story.

As you studied this Civil War history, how did you decide to write about the Charles Mitchell story?

I thought it was a story for young people. Here was a boy who didn’t accept his fate. No one knows his exact age. He was born in 1847, but in the 1850 slave census, there was no birth date given but only a hash mark. So he was twelve and a half or thirteen when he ran away.

He redealt the cards himself. He took himself to a whole different world and trusted the black men from Victoria who approached him in Olympia and said, “You don’t have to live this way. You can be free. If you come to Victoria, we’ll welcome you into our community.” And he trusted them and he remade his life. That was the impetus -- to encourage kids now who are stuck in tough circumstances that there is a future that they can make.

Judy Bentley had written several young adult biographies that I admired, so we talked, and she thought this was a great story too, and so we wrote this book together.

Didn’t Charles Mitchell come to Washington as a wedding gift to James Tilton, the chief surveyor for the territory?

There’s more than one story about Charles Mitchell’s status. His status as a gift, either as a wedding gift or an outright gift, is in the newspaper and family stories, and from James Tilton’s protest against the British government -- because James Tilton and the territorial governor did not take Mitchell’s escape lying down.

The boy was freed from the Eliza Anderson, the international mail steamer on which he stowed away with the connivance of the cook who was in on this conspiracy. The captain discovered Charlie on the way to Victoria and locked him up in the lamp room aboard the ship, and half of the black community in Victoria waited for him at the dock. They all knew the child was coming. The captain and the first mate said, “No, he’s locked up and you’re not going to get him. He’s going back to Olympia to his master.”

Three men in Victoria -- Will Davis, James Allen and William Jerome -- went to a friendly solicitor and filled out affidavits, and that’s where our paper trail begins.

The sheriff went to the boat, and the captain and first mate refused to turn over Charlie. The sheriff said, “You have no right to hold this boy under lock and key in the Crown Colony of Victoria waters.” They responded, “Yes we do,” because it was a U.S. vessel.

But eventually, to avoid bloodshed -- as the captain put it -- the boy was released to the sheriff. The boy spent that night in jail and he was freed the next day.

The captain of the ship, John Fleming, filed an affidavit of protest. Back in Olympia, Charles Mitchell’s master, James Tilton, wrote a letter of protest to the acting governor, who then wrote Secretary of State Louis Cass to protest the British seizure of Charles Mitchell. Nothing came of it. No one was going to go to war with Great Britain over Charles Mitchell.

You and Judy Bentley movingly capture the moment when Charles Mitchell’s foot touched the soil of Victoria and he became a “free boy.”

Right.

We didn’t write it for children exactly, but I think many young people will read and enjoy it. We’re also hearing from many adults who like it.

We are also very conscious that educators will use the book. Within a month, University of Washington history professor Dr. Quintard Taylor’s website blackpast.org will run a feature with primary documents that Judy and I used to research this book. Educators can see these documents, read the affidavits, the protests, the census data, and the news articles.

It’s sure to stimulate thought and discussion. What is your sense of Charles Mitchell’s life once he arrived in Olympia and began living with the James Tilton family in 1855?

The only sense we have of him is through Captain John Fleming’s eyes. We know he said to Charles Mitchell, “I know you. I remember you. I have seen you at James Tilton’s house.”

The imbalance of power between the master and the slave that existed during life, endured after death, so the archives are packed with information about James Tilton, the master, but they’re impoverished with information about the slave. It’s very difficult for us to see into his life.

In our book, Judy and I took some risks. Each chapter ends with an italicized section that is an invented scene where Charlie has dialog and gets characterization. It’s a risky thing to do, but we wanted to balance this biography.

And there are places in his life when we don’t know what happened. You asked what he did in the house in Olympia. We took the risk that he did light work -- the kind of work a nine-, ten-, eleven-year old could do: split firewood, work in the garden, pick up packages. This is not like the slavery in South Carolina. In many ways, it’s a different kind of slavery than we know anything about.

We also know that Charles Mitchell was literate. He was educated in Olympia and there’s one reference that he went to an Indian school there. But in Victoria, he went to the Boy’s Collegiate School. We have one final glimpse of him by travelers who visited the Collegiate School and said there was a black boy there who had run away from his master in Washington Territory, who wasn’t very dark and was therefore -- in their eyes -- handsome. So this is our guy at Collegiate School [which offered] a high-falutin’ college prep curriculum. We couldn’t find records of the school, so we cannot tell you how long he stayed.

Was there really a Pacific Northwest Underground Railroad?

I call it a very tiny Puget Sound Underground Railroad….

And was it a group of free blacks from Victoria who spotted Charles Mitchell and encouraged his escape?

Absolutely. It was William Jerome who saw Charles Mitchell in Olympia -- a black child in a white family. Think about it. When he was three, his mother died of cholera -- a horrible, dramatic, sudden death. His white father, an oyster fisherman on Chesapeake Bay, was not part of his life. Slavery inheres in the female line so since his mother was a slave, so he was a slave regardless of his father’s situation. And his grandparents and his aunt lived on the Marengo Plantation in Maryland, and he probably had an aunt and uncle, and cousins there. He left that family behind to go to the Pacific Northwest. It was a cruel deprivation of family for this little boy.

He’s described in the record as a mulatto -- a racial category of the time.

It was said in a couple places that he was quite light. In the racial pyramid in America in those antebellum years, white men were at the top and there’s a responsibility and sense of power that goes with that. And there’s a sort of hierarchy of people of color: the lighter you are the better.

So William Jerome was in Olympia and saw Charles Mitchell, this lovely child, and thought perhaps they could deliver and free him. Victoria was 25 percent black in 1850 and 300 of the families there had come from California and were very aware of slavery in the United States and that the Crown Colony of Victoria was free.

I would love to know more about conversations in Victoria about Charles Mitchell and about approaching him. We see the outcome but not the planning.

Did you find evidence that other slaves were helped by this underground network in the Northwest?

No, not yet. Archy Lee in California is as close as it gets. He was free really because California was a free state. He was brought there by his master and ought to have been free when he reached California, but instead the master hired him out and kept his wages. He eventually fled to Victoria. I suspect that if we find more slaves in Washington, that might be a common pattern: that a black man or woman emigrated from somewhere like Missouri or Kentucky with a white family and lived with them until death, but what happened in the meantime wasn’t easy to document. That’s one of the reasons I’m so passionate about the Read-In. I hope that we will learn more about these obscure stories.

It’s not that long ago that you and I thought there was no Civil War here to talk about. But now we know there is. The pro-Confederate, white supremacist Knights of the Golden Circle had their “castles” in Washington and Oregon, and other more moderate pro-secessionists were also here. There were efforts to purchase a steamer in Victoria and turn it into a Confederate warship. We shouldn’t forget this and pretend that everybody here was Lincoln’s friend.

There was lots of opposition to the Civil War in Washington Territory during Lincoln’s presidency. That translated into very vehement attacks on him as president. Democrats called him “King Lincoln, the Fiendish Ape,” whose arrogance sends hundreds of thousands of men to their deaths for nothing, who refused to sit down and negotiate with Jefferson Davis. These are our newspapers, our settlers -- their opinions.

Did you find evidence that people here were prosecuted under the Fugitive Slave Law?

I think that’s what was going on with the captain of the boat. Every officer of the law is charged under the Fugitive Slave Act to return slaves to their owners. But it might be that it was more informal. We know that John Fleming, the captain, said [to Mitchell]: “I know you. I’ve seen you at James Tilton’s home.” It may have meant no more than, “You’re just a kid. Why are you acting like this? I’m going to put you to work and teach you a lesson, and when you get back to Olympia, you’ll really get your hide tanned.” We don’t really know what was going on in Charlie’s head or the captain’s head or James Tilton’s head, yet it’s important to write the biography.

How many blacks were living in Washington Territory in the late 1850s?

I would estimate two or three dozen among twelve thousand settlers. Some black settlers came directly from Africa on whaling ships. Manuel Lopes, the first black in Seattle whose name we know, was Portuguese-African. He came here from the Cape Verde Islands on a whaling ship and is buried at Port Gamble.

There were other men of color, and the census enumerator was the one who decided whether you were mulatto or Negro. There were a number of sailors from coastal areas and they were free blacks back east. Then there were free blacks like the elite George Washington Bush family of Bush Prairie.

I’m obsessed with finding more people of color in Washington who were here under ambiguous circumstances. There are two letters at the University of Washington in which Edward Huggins reminisced about Fort Steilacoom during the Civil War. In between the federal censuses of 1860 and 1870, he remembered a female slave there known to him as “Mammy,” and she was the personal slave of the wife of an officer at the fort.

Where there’s one there’s two, and where there’s two, there’s got to be more. That’s where the Washington Territory Civil War Read-In comes to play so we’ll never be in the situation again of not knowing what our Civil War history was and being able to pretend the Civil War was far, far away and that the racial complacency we have is our real heritage -- when it’s not.

Wasn’t Olympia a much more established, thriving little city than Seattle in the late 1850s?

No. There was no place in Washington Territory at that time that you could call a thriving little city, compared with Victoria. There are good drawings of Olympia at the time. There was a wharf, but there was a wharf in Seattle too, and there were commercial buildings, but there were commercial buildings in Seattle too. There were very small settlements, though they were urban ones.

Olympia was the capitol, and its size varied dramatically with meetings of the legislature. I’m not sure it was bigger than Seattle. If you compare the newspapers, the Seattle Gazette to the Olympia Times Mirror and Democrat, I don’t see a great deal of difference in the kinds of businesses that were advertised.

After the Treaty [Indian] War of 1855-56, there was an outflow of population [from Washington Territory]. Some people said, “I didn’t bargain for native people at the end of the trail. Put them out on a reservation. Get them out of my sight.” But there was nowhere to go. The reservations are right here, and when native people rose against the treaty, it really freaked out a lot of settlers. So these were very small communities. And in 1860, it may well be, that there were fewer residents here than in 1855.

Is there anything you’d like to add about your hopes for the book and the significance of this story of Charles Mitchell for Washington citizens?

I think it’s significant for Washington citizens to know that we had at least one slave here and now I know of two, and I hope the Civil War Read-In turns up more.

It’s important to know that we have some kind of legacy of actual slavery and we certainly have a strong legacy of anti-black sentiment. When Oregon became a state in 1859, the settlers there voted to become a free state, but they voted by a much wider margin to bar free blacks from the territory. So you could be an abolitionist and be anti-black. You could deplore what Democrats called “Lincoln’s New Nation” of social, economic and political equity for blacks. That was just anathema to them and we’re right across the border from Oregon, and we shared a lot of the same sentiments.

Our first governor, Isaac Ingalls Stevens, was the campaign manager for the Southern wing of the Democratic Party in the 1860 election. His man John Breckinridge spent the entire Civil War in the Confederacy. The goal [of this party] was to incorporate into the Constitution an amendment that would protect slavery forever. And it would name it by that name and not dance around about property rights. So our first three governors -- Stevens, McMullen and Gholson -- were pro-slavery, pro-states’ rights, hyper-expansionist Democrats.

James Tilton was also in this group. He ran as a frank white supremacist in 1865 as a delegate for Washington Territory. There was no getting around the rhetoric of his campaign: “This is a white man’s government for white men’s progeny.” He couldn’t have been clearer. Judy and I argue that his racial attitudes were shaped in the Mexican War and hardened by his fury at Charles Mitchell’s “ingratitude” because this boy of twelve or thirteen turned away from, what seemed to Tilton, a paternal, loving, decisive guardianship.

This is where some interesting conversations can take place. Why is James Tilton called a guardian, an employer, a master, a guardian, an owner, and like a father to the boy? All of those nouns have their equivalent in the way Charles Mitchell is described as a ward, an employee, ward, property, a slave, and so forth -- including “like a son to him.” The ambiguity of this relationship interests me.

For Charles Mitchell, it was crystal clear that he was a slave and he took the risk on September 24, 1860, to get down to the Eliza Anderson dock in Olympia and let the cook hide him on board in a conspiracy to take him from Washington Territory to the Crown Colony of Victoria.

It’s important not to forget that we had this history. This book and the blackpast.org site is for educators so that we don’t go into the next generation with our fingers in our ears saying la la la la la, the Civil War is long ago and far away. The issues of the Civil War were very present here. We have no battlefields, but we had fistfights and duels and vandalism.

In your view, we study history to better understand the present, and how things got this way.

I’m a public historian. I’m not an academic, and the reason I do what I do is to help make the present make sense because if you don’t understand the past, then the present is chaotic. And if the present is chaotic, you can never make better choices for the future. So it’s very utilitarian and simple-minded, but it’s very powerful.

And I hope this book helps. I hope that teachers can use this book and the blackpast.org site in their classrooms and get their kids thinking about what it means to remake their lives. You don’t have to play the hand you’ve been dealt. You can deal yourself another one.

Robin Lindley (robinlindley@gmail.com) is a Seattle writer and attorney and features editor for the History News Network. His writing—often interviews of writers, scholars and artists—also has appeared in Crosscut, Writer’s Chronicle, Real Change, The Inlander, NW Lawyer, and other publications