Colonial Slow Genocide: Palestinian Leader Abbas asks Britain for “Balfour” Apology

Mahmoud Abbas, president of Palestine, is asking Britain for an apology for its having in 1917 issued the infamous “Balfour Declaration.” He won’t get one. The difference between the North Atlantic countries and the rest of the world is that the former are still committed to some key colonial arrangements made at the height of imperialism, which are perceived still to benefit the “West” in its grand strategy. Virtually no one in the rest of the world actively supports (as do the US and the UK) the continued expropriation of the Palestinians except the North Atlantic crowd, who perceive Israel as their human air craft carrier menacing the Middle East. (I know that the US and the UK occasionally make tut tut noises about Israeli squatter settlements on Palestinian land; these noises cannot be taken seriously given the billions in aid and other backing they proffer Tel Aviv).

On the occasion of this entirely justified demand by Palestine, I’ll share a couple of my posts that delve into the significance of that declaration, which led to settler-colonialism in the British Mandate of Palestine and to the current Apartheid state in Israel-Palestine and the statelessness and oppression at the hands of Israelis of millions of Palestinians. This extended colonialism is unparalleled in the whole world: no other colonial power now existing is keeping millions stateless and without the right to have rights. And let me point out that British authorities were told by the European Powers after Versailles that the Balfour Declaration was *not* the basis for a legal claim of Zionist Jews to Palestine and that, moreover, British high officials agreed with this objection. That is, the legislative history does not even support the conventional Zionist interpretation of Balfour to begin with. See Lord Curzon’s memo below:

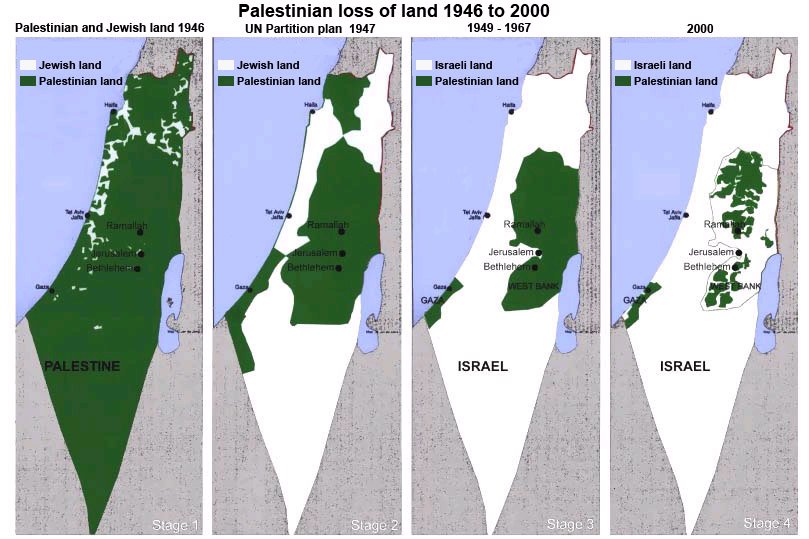

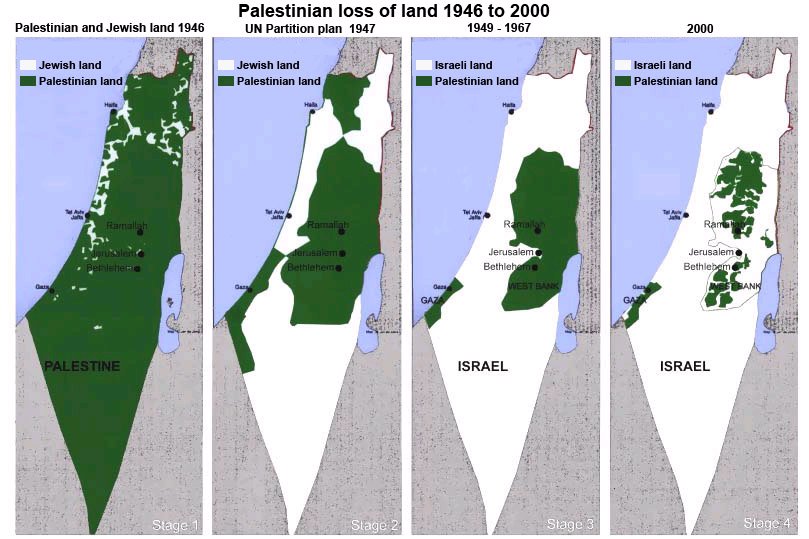

” . . . I [had] mirrored a map of modern Palestinian history that has the virtue of showing graphically what has happened to the Palestinians politically and territorially in the past century.

Andrew Sullivan then mirrored the map from my site, which set off a lot of thunder and noise among anti-Palestinian writers like Jeffrey Goldberg of the Atlantic, but shed very little light. (PS, the map as a hard copy mapcard is available from Sabeel.)

The map is useful and accurate. It begins by showing the British Mandate of Palestine as of the mid-1920s. The British conquered the Ottoman districts that came to be the Mandate during World War I (the Ottoman sultan threw in with Austria and Germany against Britain, France and Russia, mainly out of fear of Russia).

But because of the rise of the League of Nations and the influence of President Woodrow Wilson’s ideas about self-determination, Britain and France could not decently simply make their new, previously Ottoman territories into mere colonies. The League of Nations awarded them “Mandates.” Britain got Palestine, France got Syria (which it made into Syria and Lebanon), Britain got Iraq.

The League of Nations Covenant spelled out what a Class A Mandate (i.e. territory that had been Ottoman) was:

“Article 22. Certain communities formerly belonging to the Turkish Empire have reached a stage of development where their existence as independent nations can be provisionally recognised subject to the rendering of administrative advice and assistance by a Mandatory [i.e., a Western power] until such time as they are able to stand alone. The wishes of these communities must be a principal consideration in the selection of the Mandatory.”

That is, the purpose of the later British Mandate of Palestine, of the French Mandate of Syria, of the British Mandate of Iraq, was to ‘render administrative advice and assistance” to these peoples in preparation for their becoming independent states, an achievement that they were recognized as not far from attaining. The Covenant was written before the actual Mandates were established, but Palestine was a Class A Mandate and so the language of the Covenant was applicable to it. The territory that formed the British Mandate of Iraq was the same territory that became independent Iraq, and the same could have been expected of the British Mandate of Palestine. (Even class B Mandates like Togo have become nation-states, but the poor Palestinians are just stateless prisoners in colonial cantons).

The first map thus shows what the League of Nations imagined would become the state of Palestine. The economist published an odd assertion that the Negev Desert was ’empty’ and should not have been shown in the first map. But it wasn’t and isn’t empty; Palestinian Bedouin live there, and they and the desert were recognized by the League of Nations as belonging to the Mandate of Palestine, a state-in-training. The Mandate of Palestine also had a charge to allow for the establishment of a ‘homeland’ in Palestine for Jews (because of the 1917 Balfour Declaration), but nobody among League of Nations officialdom at that time imagined it would be a whole and competing territorial state. There was no prospect of more than a few tens of thousands of Jews settling in Palestine, as of the mid-1920s. (They are shown in white on the first map, refuting those who mysteriously complained that the maps alternated between showing sovereignty and showing population). As late as the 1939 British White Paper, British officials imagined that the Mandate would emerge as an independent Palestinian state within 10 years.

In 1851, there had been 327,000 Palestinians (yes, the word ‘Filistin’ was current then) and other non-Jews, and only 13,000 Jews. In 1925, after decades of determined Jewish immigration, there were a little over 100,000 Jews, and there were 765,000 mostly Palestinian non-Jews in the British Mandate of Palestine. For historical demography of this area, see Justin McCarthy’s painstaking calculations; it is not true, as sometimes is claimed, that we cannot know anything about population figures in this region. See also his journal article, reprinted at this site. The Palestinian population grew because of rapid population growth, not in-migration, which was minor. The common allegation that Jerusalem had a Jewish majority at some point in the 19th century is meaningless. Jerusalem was a small town in 1851, and many pious or indigent elderly Jews from Eastern Europe and elsewhere retired there because of charities that would support them. In 1851, Jews were only about 4% of the population of the territory that became the British Mandate of Palestine some 70 years later. And, there had been few adherents of Judaism, just a few thousand, from the time most Jews in Palestine adopted Christianity and Islam in the first millennium CE all the way until the 20th century. In the British Mandate of Palestine, the district of Jerusalem was largely Palestinian.

The rise of the Nazis in the 1930s impelled massive Jewish emigration to Palestine, so by 1940 there were over 400,000 Jews there amid over a million Palestinians.

The second map shows the United Nations partition plan of 1947, which awarded Jews (who only then owned about 6% of Palestinian land) a substantial state alongside a much reduced Palestine. Although apologists for the Zionist movement say that the Zionists accepted this partition plan and the Arabs rejected it, that is not entirely true. Zionist leader David Ben Gurion noted in his diary when Israel was established that when the US had been formed, no document set out its territorial extent, implying that the same was true of Israel. We know that Ben Gurion was an Israeli expansionist who fully intended to annex more land to Israel, and by 1956 he attempted to add the Sinai and would have liked southern Lebanon. So the Zionist “acceptance” of the UN partition plan did not mean very much beyond a happiness that their initial starting point was much better than their actual land ownership had given them any right to expect.

The third map shows the status quo after the Israeli-Palestinian civil war of 1947-1948. It is not true that the entire Arab League attacked the Jewish community in Palestine or later Israel on behalf of the Palestinians. As Avi Shlaim has shown, Jordan had made an understanding with the Zionist leadership that it would grab the West Bank, and its troops did not mount a campaign in the territory awarded to Israel by the UN. Egypt grabbed Gaza and then tried to grab the Negev Desert, with a few thousand badly trained and equipped troops, but was defeated by the nascent Israeli army. Few other Arab states sent any significant number of troops. The total number of troops on the Arab side actually on the ground was about equal to those of the Zionist forces, and the Zionists had more esprit de corps and better weaponry.

The final map shows the situation today, which springs from the Israeli occupation of Gaza and the West Bank in 1967 and then the decision of the Israelis to colonize the West Bank intensively (a process that is illegal in the law of war concerning occupied populations).

There is nothing inaccurate about the maps at all, historically. Goldberg maintained that the Palestinians’ ‘original sin’ was rejecting the 1947 UN partition plan. But since Ben Gurion and other expansionists went on to grab more territory later in history, it is not clear that the Palestinians could have avoided being occupied even if they had given away willingly so much of their country in 1947. The first original sin was the contradictory and feckless pledge by the British to sponsor Jewish immigration into their Mandate in Palestine, which they wickedly and fantastically promised would never inconvenience the Palestinians in any way. It was the same kind of original sin as the French policy of sponsoring a million colons in French Algeria, or the French attempt to create a Christian-dominated Lebanon where the Christians would be privileged by French policy. The second original sin was the refusal of the United States to allow Jews to immigrate in the 1930s and early 1940s, which forced them to go to Palestine to escape the monstrous, mass-murdering Nazis.

The map attracted so much ire and controversy not because it is inaccurate but because it clearly shows what has been done to the Palestinians, which the League of Nations had recognized as not far from achieving statehood in its Covenant. Their statehood and their territory has been taken from them, and they have been left stateless, without citizenship and therefore without basic civil and human rights. The map makes it easy to see this process. The map had to be stigmatized and made taboo. But even if that marginalization of an image could be accomplished, the squalid reality of Palestinian statelessness would remain, and the children of Gaza would still be being malnourished by the deliberate Israeli policy of blockading civilians. The map just points to a powerful reality; banishing the map does not change that reality.

”

And here is the concluding document for this discussion:

I posted Tuesday on the legal implications of the League of Nations’ recognition of Palestine as a “Class A” Mandate, i.e. a former Ottoman territory nearly ready for national independence, to which the mandatory authority (i.e. Britain) was to lend ‘administrative assistance’ in its attainment of independence. I received some strange mail from fanatics afterward, insisting that the British Mandate of Palestine was not recognized as a Class A Mandate. A scholar also wrote me to point out that unlike the case with Iraq and Syria, the British brought the Balfour Declaration into the Mandate document. The latter is true, but not relevant to my point, since the League of Nations interpreted the language of the declaration differently than did the Zionists. Others complained that the map starts in the mid-1920s after the British had already hived off Transjordan. But so what? If Class A Mandates were almost ready for independence, why couldn’t some portion of them be granted independence first? The French also split the Mandate of Syria into two parts, Syria and Lebanon. What has that got to do with anything?

The legal history does not bear out any of these objections to my argument. The following British archival document makes it very clear that the British were forced by France and Italy not to disregard the interests of the over 90% of their mandate that was Palestinian, and that London revised its Mandate document under pressure as a result. The League of Nations created and granted the Mandate, contrary to what Balfour kept sputtering (he was not even in office 1922-1924). What the victorious Powers and the League of Nations wanted has to be part of the interpretation of the Mandate’s charge. The League of Nations wanted the British Mandate of Palestine to serve the Palestinians in accordance with their status as “Class A.” It envisaged a Palestinian state. Indeed, Sir Herbert Samuel, the first governor of the British Mandate of Palestine, urged that the “future government of Palestine” be required to repay any loans raised during the Mandate for its development. So they envisaged a future government of Palestine, which they assumed would be overwhelmingly Palestinian.

As for the language about a Jewish homeland, by that was not meant a territorial state on Palestinian land. Curzon is clear that although the Powers at the Versailles conferences after WW I recognized a Jewish connection to Palestine and the Balfour Declaration, “this was far from constituting anything in the nature of a legal claim . . .” He also reports that the Powers said that “while Mr. Balfour’s Declaration had provided for the establishment of a Jewish National Home in Palestine, this was not the same thing as the reconstitution of Palestine as a Jewish National Home–an extension of the phrase for which there was no justification . . .”

So here is the Memorandum of Lord Curzon, British Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, concerning League of Nations “Class A” Mandates in November 30, 1920. British National Archives, Catalogue Reference: CAB/24/115. Crown copyright. (Note that I am not reproducing the entire document, leaving out some discussion of arrangements in Iraq):

MANDATES A.

MEMORANDUM BY THE SECRETARY OF STATE FOR FOREIGN AFFAIRS. [Lord Curzon].

A FINAL decision about Mandates A is required. The Assembly of the League of Nations is concerned about their submission to the Council, and will probably not allow the gathering at Geneva to come to an end without a decision being taken on the point.

It is understood that the Council of the League is likely to hold a meeting while at Geneva to consider these Mandates, and it has been informed that they will be submitted without further delay. The Mandates concerned are those for Syria, Mesopotamia and Palestine.

The French Mandate for Syria is drawn on the same lines as ours for Mesopotamia, though not actually identical with it. There is nothing in it to which we desire to object.

The Mandate for Mesopotamia has passed through several stages, tending in each case to further simplification. It has been shown to, and approved by, the French and Italian Governments, to whom we were under a pledge at San Remo to submit it In its last printed form this Mandate was approved by the Cabinet a few weeks ago . . .

As regards the Palestine Mandate, this Mandate also has passed through several revises. When it was first shown to the French Government it at once excited their vehement criticisms on the ground of its almost exclusively Zionist complexion and of the manner in which the interests and rights of the Arab majority (amounting to about nine-tenths of the population) were ignored. The Italian Government expressed similar apprehensions. It was felt that this would constitute a very serious, and possibly a fatal, objection when the Mandate came ultimately before the Council of the League. The Mandate, therefore, was largely rewritten, and finally received their assent. It was also considered by an Inter-Departmental Conference here, in which the Foreign Office, Board of Trade, War Office and India Office were represented, and which passed the final draft.

In the course of these discussions strong objection was taken to a statement which had been inserted in the Preamble of the first draft to the following effect:— ” Recognising the historical connection of the Jewish people with Palestine and the claim which this gives them to reconstitute Palestine as their National Home.”

367 [4996]

It was pointed out (1) that, while the Powers had unquestionably recognised the historical connection of the Jews with Palestine by their formal acceptance of the Balfour Declaration and their textual incorporation of it in the Turkish Peace Treaty drafted at San Remo, this was far from constituting anything in the nature of a legal claim, and that the use of such words might be, and was, indeed, certain to be, used as the basis of all sorts of political claims by the Zionists for the control of Palestinian administration in the future, and ;2) that, while Mr. Balfour’s Declaration had provided for the establishment of a Jewish National Home in Palestine, this was not the same thing as the reconstitution of Palestine as a Jewish National Home–an extension of the phrase for which there was no justification, and which was certain to be employed in the future as the basis for claims of the character to which I have referred. On the other hand, the Zionists pleaded for the insertion of some such phrase in the preamble, on the ground that it would make all the difference to the money that they aspired to raise in foreign, countries for the development of Palestine. Mr. Balfour, who interested himself keenly in their case, admitted, however, the force of the above contentions, and, on the eve of leaving for Geneva, suggested an alternative form of words which I am prepared to recommend.

Paragraph 3 of the Preamble would then conclude as follows (vide the words italicised in the Draft-;

” and whereas recognition lias thereby (i.e., by the Treaty of Sevres) been given to the historical connection of the Jewish people with Palestine, and to the grounds for reconstituting their National Home in that country.”

Simultaneously the Zionists pressed for the concession of preferential rights for themselves in respect of public works, &c, in Article 11.

It was felt unanimously, and was agreed by Mr. Balfour, that there was no ground for making this concession, which ought to be refused. . .

During the last few hours a telegram has been received from Sir H. Samuel, urging that, in order to facilitate the raising of loans by the Palestine Administration, which will otherwise be impossible, words should be added to Article 27, providing that on the termination of the Mandate, the future Government of Palestine shall fully honour the financial obligations incurred by the Palestinian Administration during the period of the Mandate. This appears to be a quite reasonable demand, and I have accordingly added words (italicised at the end of Article 27) in order to meet it. With this explanation, therefore, I hope that the Mandates in the form now submitted may be formally passed and forwarded to the Council of the League.

C. OF K. November 30, 1920.