The Striking and Disturbing Parallel Between the 1930s and Our Own Time

There is an understandable desire to explain Trump and Trumpism by comparing him to past individuals and movements. Although understanding Trump and Trumpism in this way is useful, it runs the risk of attributing too much influence to one person. Focusing on the leader disregards the social and political environment and the people that helped bring that leader or movement to power. Instead, it is often more fruitful look at broader historical patterns in the past to understand our present.

To best understand Trump we need to situate him in historical context. What social, cultural and economic situation that brought Trump to the Oval Office? Trumpism and Fascism are both a response to a rapidly changing world where social, political and economic institutions failed to adapt. In The Anatomy of Fascism, historian Robert Paxton sees fascism as a response to the fundamental and rapid changes that occurred at the turn of the 20th century, which culminated in World War I. Trump can also be seen as a response to the dizzying changes that occurred at the turn of the 21st century, which culminated in the Great Recession. In both cases, the subsequent crisis magnified the inadequacy of the prior order, and a nativist authoritarianism stepped in. Neither Trump nor Mussolini grasped the reins of history; they rode its coattails.

In both periods the time leading up to the crisis was one of profound and swift change. At the turn of the 20th century new technology disrupted established economic patterns. Paxton lists an array of changes that stressed the social fabric of society. Steamships brought cheap food to Europe, putting pressure on family farms. Railroads and new factories hurt skilled artisanal labor. Cities swelled with rural refugees. Huge numbers of immigrants – workers from Spain and Italy, but also ever maligned Jews from Eastern Europe – added to perceived stresses on community solidarity.

A similar socio-political upheaval existed in the United States at the turn of the 20th century. Globalization put downward pressure on wages and drove jobs offshore. The cheap goods made available by an increasingly connected world also had a downside. Automation caused further pressure. Huge numbers of immigrants made for easy scapegoats. Income inequality and the demand of marginalized social groups for a seat at the table – both problems originating in the nation’s founding – became more salient. The information revolution has changed the way society we interact with in very profound ways.

In both periods the overwhelming change and disruption culminated in a catastrophic event. World War I dispelled Europe of the promises of liberalism and of the inevitability of European progress. Socially, it created huge numbers of restless, angry veterans who sought ways to express their anger. Politically, most liberal states and societies barely managed to meet these new challenges. Some crumbled beneath them. In Paxton’s view fundamental liberal institutions like parliament, market and school were not able to meet these new challenges. Shocked that liberal European culture could have culminated in trench warfare, large groups of populations sought answers and a way forward.

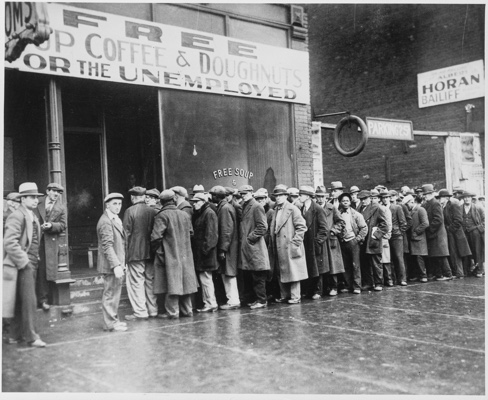

Just as World War I laid bare the hollow core of the pre-war order, so too the Great Recession shattered belief in the liberal American Dream. When the dust began to settle after the implosion of 2008, Americans had a better perspective on the social and political institutions that undergirded the system. The rich controlled the economy. Huge numbers of people were out of work or had jobs that did not pay a living wage. Politicians were mouthpieces for the Fortune 100. Many social groups were marginalized and discriminated against, despite the lip service paid to the creed that economic growth would lift all Americans in equal measure. The prior order had failed, and the liturgy of capitalism and democracy preached by elites was recast in a new light – income inequality and kleptocracy.

Both Trump and early fascist movements played on the political chaos that ensued after the culminating crisis. They stoked the fear and anger of the victims of rapid economic change and globalization. In the words of Frank Rich, “Trump’s genius has been to exploit and weaponize the discontent that has been brewing over decades of globalization and technological upheaval.” Both played on the primacy of the in-group and the fear of immigrants and the need for a strong (male) leader as the only man who has the talents and “greatness” to right wrongs and steer the Volk back to its proper place at the vanguard of the Darwinian struggle.

Many have said that U.S. political institutions are far stronger than those of Western Europe on the eve of World War I. To a certain extent they are right. But our democracy is not as strong or as adaptable as it would seem. Democratic institutions are good at mitigating social conflict, but there is always a point at which the intensity of conflict exceeds the capacity of the institutions. World War I and the rise of Fascism are good examples of what happens when institutions fail to adapt to social and political change. Understanding the conditions in which they rose helps us to understand the more recent conditions that gave rise to our present.