The History of Black Women Championing Demands for Reparations

The American media has paid increasing attention to the legacies of slavery. The new National Museum of African American History and Culture features a huge exhibition on the history of slavery. Many US universities are studying their links with slavery and the slave trade. In several cases, schools decided to provide symbolic reparations by renaming buildings and/or creating memorials and monuments to honor enslaved men and women.

But these measures do not seem to suffice: several activists and ordinary citizens are calling for financial reparations. Students of Georgetown University recently voted to pay a fee to finance a reparations fund to benefit the descendants of the 1838 sale of enslaved people owned by the Society of Jesus. The Democratic presidential candidates are routinely asked if they would support studies to provide financial reparations for slavery to African Americans. What is often missed is that these calls started long ago. Writers and readers also forget that black women championed demands of reparations for slavery.

Belinda Sutton is among the first black women to demand reparations for slavery in North America. Her owner, Isaac Royall Junior, fled North America in 1775, during the American Revolutionary War. He left behind his assets but his will included provisions to pay Belinda a pension for three years.

After Royall Junior’s death, we assume Sutton received the pension determined in his will. When three years passed, the payments stopped. Belinda petitioned the Massachusetts legislature and requested her pension continue. Emphasizing she lived in poverty and had contributed to the wealth of the Royalls, Sutton successfully obtained an annual pension. Belinda’s story is memorialized at the Royall House and Slave Quarters in Medford, Massachusetts.

Like today, the political context shaped these early demands for reparations and the responses petitioners received. Unlike other former slaves, Sutton’s odds to get restitutions were greater because her former owner was a British Loyalist. Moreover, he had already determined in his will to pay her a pension.

Freedwomen and their descendants continued fighting for reparations in later years. They knew more than anyone else the value of material resources because they lacked them. They were those providing hard work to maintain their households and to raise children and grandchildren.

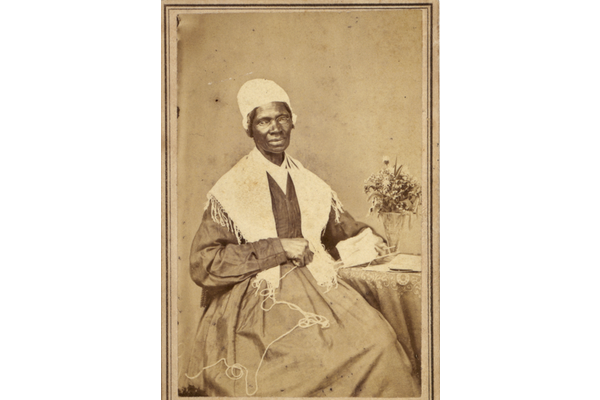

Sojourner Truth also demanded reparations for slavery through land redistribution. Following the end of slavery, during Reconstruction, Truth argued that slaves helped to build the nation’s wealth and therefore should be compensated. In 1870, she circulated a petition requesting Congress to provide land to the “freed colored people in and about Washington” to allow them “to support themselves.” Yet, Truth’s efforts were not successful. US former slaves got no land or financial support after the end of slavery.

The context of the brutal end of Reconstruction that cut short the promises of equal access to education and voting rights for black Americans favored the rise of calls for reparations. And once again black women took the lead.

Ex-slave Callie House fought for reparations. A widow and a mother of five children, who worked as a washerwoman, she saw many former slaves old, sick, and unable to work to maintain themselves. House became one of the leaders of the National Ex-Slave Mutual Relief, Bounty and Pension Association that gathered dozens of thousands of former slaves to press the US Congress to pass legislation to award pensions to freedpeople.

Soon the federal government started accusing the association of using mail to lead a fraud scheme. Callie House responded that the association’s goal was to obtain redress for a historical wrong. She reminded federal authorities that former slaves were left with no resources and had the right to organize themselves to demand restitutions. She bravely denounced that government hostility against the pensions movement was motivated by racism.

In 1916, the Post Office Department charged Callie House for using the US mail to defraud. She spent one year in prison.

Black women had good reasons to fight for reparations. Until the 1920s, black women were deprived of voting rights. More than black men, they were socially and economically excluded. With less access to education, even in an old age they were those running the households. To most former enslaved women, expectations of social mobility were impracticable. In contrast, pensions and land were tangible resources that could supply them with autonomy and possible social mobility.

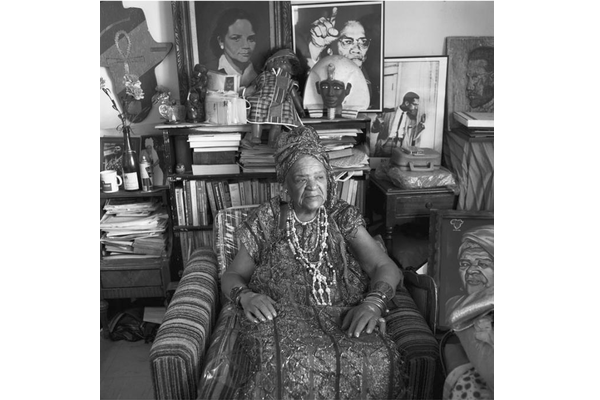

Audley Eloise Moore from Louisiana also became an important reparations’ activist. Influenced by Marcus Garvey she became a prominent, black nationalist, Pan-Africanist, and civil rights activist.

In 1962, Moore saw the approach of the one hundredth anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 as an occasion to discuss the legacies of slavery. To this end, she created the Reparations Committee for the Descendants of American Slaves (RCDAS) that filed a claim demanding reparations for slavery in a court of the state of California. She also authored a booklet underscoring that slaves provided dozens of years of unpaid work to slave owners. She emphasized the horrors of lynching, segregation, disfranchisement, raping, and police brutality. Yet, the litigation was not successful.

Moore defended payment of financial reparations to all African Americans and their descendants and that each individual and group should decide what to do with the funds. She contended that the unpaid work provided by enslaved Africans and their descendants led to the wealth accumulation that made the United States the richest “the richest country in the world.”

In later years, Moore continued participating in organizations defending reparations for slavery. In 1968, she joined the Republic of New Africa and later supported the efforts of the National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America (N’COBRA). She made her last public appearance at her late nineties during the Million Man March held in Washington DC in October 1995, when she still called for reparations.

In 2002, Edward Fagan filled a class-action lawsuit in the name of Deadria Farmer-Paellmann and other persons in similar situations. An African American activist and lawyer, Farmer-Paellmann founded the Reparations Study Group. Fagan’s lawsuit requested a formal apology and financial reparations from three US companies that profited from slavery. Among these corporations was Aetna Insurance Company that held an insurance policy in the name of Abel Hines, Farmer-Paellman’s enslaved great-grandfather. Although the case was dismissed in 2004, the US Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit later allowed the plaintiffs to engage in consumer protection claims exposing the companies named in the lawsuit for misleading their customers about their role in slavery.

Years marking commemorative dates associated with slavery favor the rise of demands of reparations. This year marks the fourth hundredth anniversary of the landing of the first enslaved Africans in Virginia. In addition, it’s also the kick off of the 2020 presidential campaign.

For black groups and organizations that now fully engage in social media it’s time to renew calls for reparations that have been around for several decades. For potential presidential candidates, the debate on reparations is an opportunity to gain the black vote.

But for black women, no matter the commemorative and elections calendars, the fight for reparations is not a new opportunity, it is rather a long-lasting battle for social justice.