Bernie Sanders, Social Democracy, and Democratic Socialism

Bernie Sanders is the best kind of social democrat and sort of a democratic socialist. He roars against economic corruption, severe inequality, and donor class politics, protesting that Wall Street Democrats dominate the Democratic Party. He espouses a welfare state politics of economic rights, which he calls, with a modicum of historical warrant, democratic socialism. Sanders wants the U.S. to institute policies that social democratic governments achieved long ago in Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden, and Germany, and he opposes authoritarian forms of socialism, contrary to an incoming avalanche of red-baiting. He resolved forty years ago to wear the socialist label as a badge of honor since people were going to call him one anyway. This decision served him well until now. Now he is obliged, with much at stake, to explain more than ever what the s-word does not mean to him.

I say this as a longtime supporter of Sanders and as a current supporter of Elizabeth Warren who believes that she is the best candidate to unite the Democratic Party and attract various others to it. Taking ethical responsibility for the likeliest electoral outcome of November 2020 is a very serious business. But my subject is the democratic socialism of Sanders, which looms ever larger in American politics after the Iowa and New Hampshire primaries.

Classic democratic socialism calls for centralized public ownership of essential enterprises, or worker ownership, or mixed forms of public and worker ownership, either decentralized or not. But Sanders has never pushed for any of these things. The closest that he comes to classic democratic socialism is his plank calling for worker control of up to 45 percent of board seats and 20 percent of shares. Similar planks in European platforms have long marked the boundary between modern social democracy and democratic socialism. In Germany, all companies employing more than 1,000 workers have been required since 1951 to institute a supervisory board consisting of 50 percent worker representatives and 50 percent management representatives. German codetermination has been a firewall against runaway manufacturing plants, since workers do not sabotage their own jobs. The Swedish version of codetermination, a union capital fund called the Meidner Plan for Economic Democracy, would have crossed the line eventually from social democracy into democratic socialism. But it was scuttled in 1992 after a 10-year run, confirming that even in Sweden the guardians of neoliberal capitalism do not tolerate transitions to a different kind of system.

Social democracy and democratic socialism have never completely overlapped. Originally, “social democracy” named all socialists that rejected anarchism and ran for political office, while “democratic socialism” named the flank of social democrats that insisted on the liberal democratic road to socialism. Democratic socialists contended against their Marxian comrades that democracy is the indispensable road to socialism, not a byproduct of achieving it. Social democracy was a name for the broad socialist movement and democratic socialism was a liberal-democratic flank of it.

But “social democracy” acquired a different meaning after European socialists compiled records in electoral politics and shed much of their Marxian background. Their prolonged struggle against Communism was formative and defining, as was their swing away from collective ownership after World War II. “Social democracy” came to signify what democratic socialists actually did when they ran for office and gained power. They did not achieve democratic socialism, the radical idea of social and economic democracy. They added socialist programs to the existing system, building welfare states undergirded by mixed economies.

“Social democracy” became synonymous with European welfare states in which the government pays for everyone’s healthcare, higher education is free, elections are publicly financed, and solidarity wage policies restrain economic inequality. In the United States, meanwhile, healthcare depends on what you can afford, many have no health coverage at all, students enter the workforce with crippling debt, private money dominates the political system, and severe inequality worsens constantly. Sanders has long challenged the U.S. to aspire to social democratic standards of social decency. In his early career he called it “socialism” because he was a stubborn type who didn’t flinch at red-baiting and the social democratic parties no longer talked about economic collectivism. Then he found himself speaking to a generation that grew up under neoliberalism and does not remember the Cold War.

Occupy Wall Street, in 2011, was a harbinger that people are fed up and a breaking point had been reached. Forty years of letting Wall Street and the big corporations do whatever they want yielded protests against flat wages, extreme inequality, the specter of eco-apocalypse, and the neoliberal order. The way that Sanders describes democratic socialism is prosaic in comparison to its history and in the context of the global rebellion to which he speaks. He conceives democratic socialism as the fitting name for his belief that a living wage, universal healthcare, a complete education, affordable housing, a clean environment, and a secure retirement are economic rights.

These six economic rights come from Franklin Roosevelt’s 1944 Economic Bill of Rights. The much-dreaded “radicalism” of Sanders is in fact a throwback to FDR’s State of the Union Address of 1944. Sanders lines up with FDR, Martin Luther King Jr., and Catholic social teaching in believing that real freedom includes economic security. In November 2015 at Georgetown, he reeled off 32 paragraphs about what democratic socialism means to him. All were FDR themes in social democratic language: “Democratic socialism means that we must create an economy that works for all, not just the very wealthy. Democratic socialism means that we must reform a political system in America today which is not only grossly unfair, but, in many respects, corrupt.”

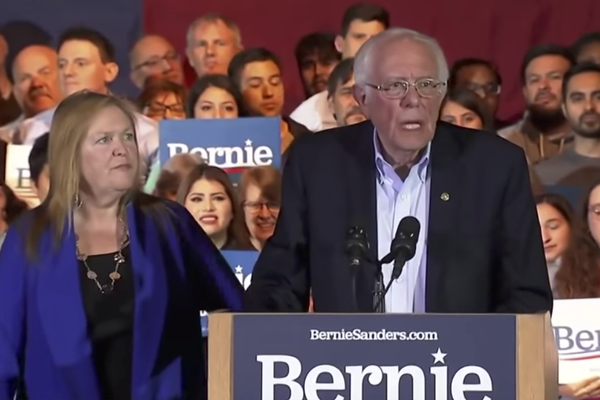

Today he is building upon the spectacular campaign he ran in 2016, rewarded for decades of never wavering on behalf of equality. Last time it showed that Sanders didn’t know many black or Latino organizers and had spent his career speaking mainly to white Vermont audiences. This time his campaign feels much less white and Old Left. The Sanders campaign is a social movement, as he says, not a conventional campaign. Sanders is a magnet for many progressives who hold no interest in joining the Democratic Party and who trust that he is no more of a Democrat than they are. My qualm about his candidacy is that he will not be able to unify the party if he is nominated; Sanders has been a terribly solitary figure in the Senate for a long time. But the party bosses must let this play out without cheating him as they did last time. And they really must resist red-baiting the person who may emerge as their nominee.