"My Entire Career has Led Me to this Project": HNN Interviews Kevin Kruse

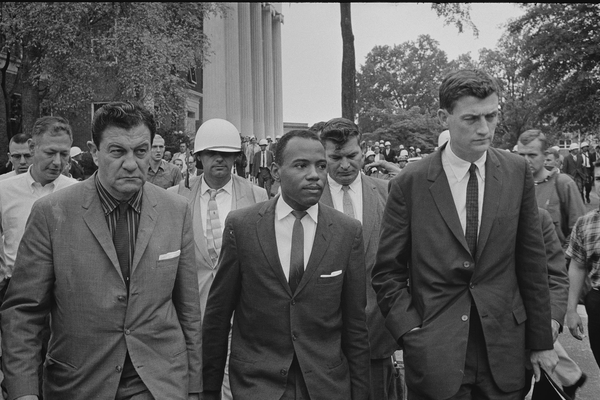

John Doar (R) with James Meredith at the integration of the University of Mississippi, 1962.

Chelsea Connolly and Hana Hancock recently conducted a virtual interview with Kevin Kruse for HNN about his new research on Department of Justice attorney John Doar's work during the Civil Rights movement, his activities as a publicly engaged historian, and historians' place in public discourse. Their questions and his answers follow:

John Doar was one of the public faces of the Justice Department at a time when the civil rights movement put tremendous pressure on that agency. Has studying Doar's career changed your understanding of the relationship between institutions and social change?

The importance of various institutions in the civil rights revolution has always been stressed in the literature, to one degree or another, and this project has only deepened my sense of their importance. But it’s also complicated my understanding in important ways, leading me to reconsider broad institutions that are often presented as a unified whole — “the Johnson administration” — and see them instead as a more complex set of smaller institutions with competing and often conflicting agendas. The lawyers in the Civil Rights Division had to address with pressures above them in the White House and below them, so to speak, at the grass roots, but they also had a considerable number of allies and enemies within the administration, ranging from running conflicts with Hoover’s FBI within the same Department of Justice to growing alliances with liberal forces in departments like HEW and HUD. These institutions mattered, but more important, individuals in them like Doar mattered as well.

Doar was present in a number of historically and culturally significant Civil Rights events. Why do most people not know about him and why should we?

It’s a bit overwhelming to think about how Doar was connected to so many well-known flashpoints in the civil rights revolution, from the Freedom Rides and James Meredith’s integration of Ole Miss to the “Mississippi Burning” trial and the Selma-to-Montgomery March, not to mention dozens of other crises that are less well-known. He was certainly well-known to all sides of the struggle at the time, with civil rights activists carrying his phone number into Mississippi and segregationist officials loathing him by name. But it’s true that his name is not well known today.

I think that’s largely due to the ways in which he operated at the time and the ways in which he protected his legacy later. During his days at the Civil Rights Division, he operated on the principle that you could do anything if you didn’t care who got the credit, and so he often passed credit up to his superiors or down to local officials, as needed. And then once he retired, he kept his papers private until after his death, and as a result, his role wasn’t well appreciated by researchers. But now that the Doar Papers have opened at Princeton, I suspect that’s going to change quite quickly.

Did Doar face any opposition at the Department of Justice, given the volatile atmosphere he encountered many times over in the South?

He had the strong support of his superiors in the Civil Rights Division and the Attorney General, but there was a good deal of friction with the FBI. When Doar arrived in the division in 1960, he quickly learned that the early voting rights suits filed by the division had gone nowhere due to the lack of evidence provided by the FBI. Director J. Edgar Hoover considered the civil rights movement a communist menace to good order, and his agents followed his lead in handling the matter. When asked to investigate voting discrimination cases, FBI agents provided clipped literal answers that largely confirmed information already available in news accounts. Doar changed that, issuing lengthy memos with dozens and dozens of questions that had to be answered in methodical detail. The FBI resented the intrusion.

What does Doar tell us about the allies of the Civil Rights movement and the role that they played?

He shows that the federal government — or parts of it, anyway — were more sympathetic to the cause of civil rights and more engaged in protecting activists and promoting their cause. Doar understood the limits of his office’s abilities and warned activists that he couldn’t protect them in the South at all times, but his diligence and activism certainly kept some additional segregationist violence in check.

What is it like to use John Doar's papers, a previously untapped resource of primary documents, for research?

It’s an incredible collection, in every sense. It’s quite large, with something like 280 large bankers’ boxes of material, and it’s also quite rich in detail. I’ve not only learned a great deal about previously undiscussed aspects of the civil rights struggle, but I’ve unearthed some fascinating new details about events we thought we already knew quite well. I’m excited to share some of these findings in my forthcoming book, but even then I’ll only be able to present a small portion of this material. I think this collection will keep civil rights historians busy for quite some time.

In your opinion, how does the experience of writing a biography differ from other types of historical writing?

This project has evolved into more of an institutional biography, with Doar at its center, rather than being a straightforward biography, so I’m not sure I can answer that question precisely. But I will say the experience of having one central figure at the heart of the history I’m seeking to relate is a rather new experience. My previous work focused on larger entities, ranging from a city like Atlanta to a political movement like religious nationalism or the entire country writ large. It’s at once easier, in that the boundaries of the project draw themselves naturally, and harder, in that I feel compelled to account for as much of the subject as I possibly can. With a larger project, I’ve felt free to follow the narrative arc of the history where it seemed to lead, while here I’m feeling obligated to account for the whole of the individual or the institution in ways I haven’t before.

How does Doar’s story fit into your broader interest in 20th century American political and social history?

I’ve felt that my entire career has led me to this project. My first book (White Flight) was a grassroots study of segregation and civil rights, my second (One Nation Under God) looked more to Washington DC to explore a different political change, and the third (Fault Lines) took an even broader perspective on the nation as a whole. This one will bring all those perspectives together, while returning me to my first love, the civil rights era.

You are an academic historian, yet you are also very publicly engaged. Why do you believe it is important for historians to "break out of the ivory tower," so to speak?

I think most historians share my belief that we have an obligation to engage with the general public in some fashion. Our approaches may vary — some writing op-eds and essays, others popping up in radio or TV to add historical insight, or still more working on social media or podcasts to advance their own message, etc — but at heart we’re all teachers and looking to reach as many people as possible.

And in this convoluted era of “fake news” and hyperpolarized history, I think our work is especially vital. As much as doctors have an obligation to push back against the anti-vaccine crowd or climate scientists have an obligation to push back against climate change deniers, historians have a duty to push back against the lies and misrepresentations made about our history. We have a special set of expertise that needs to be shared with the general public.

Academic communities, like the rest of the world, are being affected by a pandemic now. As a historian, what do you think about this moment? What can historians contribute to the discourse?

Historians, as always, provide vital context in a crisis. Historians who specialize in past pandemics, public health and medicine, of course, have a particularly important role to play here, but I think virtually every historian has something to contribute. This pandemic is global in scale and personal in impact, and as a result, it’s touching and transforming virtually every topic that historians have studied. We have a duty to share our insights with the larger world. They’re interested in what we have to say. (And, let’s remember, most of them are stuck at home looking for something to read!)