Interconnected Histories of Race, Violence, and Policing in America

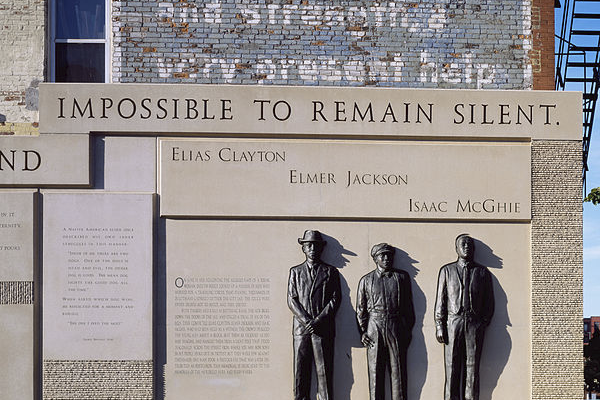

Memorial to the three victims of the 1920 Duluth, Minnesota lynching.

Even amid the continuing COVID-19 pandemic, the United States in recent days has experienced profound reminders of the legacies of its interconnected histories of lynching and brutal, racially disparate policing, histories that span American regions. In February, several white men in Glynn County, Georgia, shot and killed Ahmaud Arbery, a 25-year-old African American jogger whom they claimed may have committed burglary. Local authorities initially failed to charge Travis and Gregory McMichael in Arbery’s death. After media coverage and national scrutiny, Georgia authorities brought charges in May against the McMichaels and a third man, William “Roddie” Bryan Jr., who had filmed Arbery’s killing.

The fatal arrest on Memorial Day of George Floyd, a 46-year-old African American accused of trying to use a fake twenty-dollar bill, led to days of protest and looting and calls for charges of murder to be brought against the four police officers involved. As vividly captured in a widely viewed video, one of the officers, Derek Chauvin, for more than eight minutes held his knee to Floyd’s neck as the handcuffed Floyd pleaded that he could not breathe. While the Minneapolis police chief fired the four officers the next day and Chauvin was arrested and charged with third degree-murder and manslaughter on May 29th, Floyd’s death joined a lengthy list of African American men who had died at the hands of police, including Eric Garner, who died on Staten Island in July 2014 while similarly held down by a police officer after pleading that could not breathe.

These recent incidents painfully illustrate that America’s racial past is hardly past but rather powerfully connects past and present. The vigilante killing of Ahmaud Arbery resembles Jim Crow era Southern lynchings in the McMichaels’ assumption of white citizens’ prerogative to lethally punish supposed African American deviancy outside of formal due process channels, with at least initially the connivance of local criminal justice authorities. The lethal brutality that the Minneapolis police deployed against George Floyd connects with the ways in which excessive, racially disparate policing emerged from lynching. It also reflects the Midwest and the North’s long participation in American racism and racial violence, despite many white Northerners’ and white Midwesterners’ conception of themselves as racially innocent, free from white Southerners’ links to the overt racial oppression of slavery, lynching, and Jim Crow.

Yet the North and the Midwest were never racially innocent. Irish American mobs in Milwaukee in 1861 and in Newburgh, New York, and New York City in 1863 were among the first whites to lynch free African Americans, anticipating the several thousand African Americans who would be lynched in the South in the decades that followed the emancipation of the slaves in 1865. In Duluth, Minnesota, in June 1920, a mob of several thousand whites lynched three African American circus employees falsely accused of raping a white woman, an event remembered in a memorial dedicated by the city of Duluth in 2003. White urbanites in the North violently policed the color line during the several decades-long Great Migration of blacks from the rural South to Northern cities, rioting in Chicago in 1919 and again against the integration of urban neighborhoods in the 1960s. After Martin Luther King, Jr. experienced white Chicagoans protesting against integration in Marquette Park in August 1966, King told reporters, “I’ve been in many demonstrations all across the South, but I can say I have never seen—even in Mississippi and Alabama—mobs as hostile and as hate-filled as I’ve seen here in Chicago.”

Crucially, Southern and Northern police forces in the twentieth century assumed functions that had previously been left to non-state actors such as slaveholders, the slave patrol and after the Civil War, to lynch mobs: the extralegal use of lethal force to punish allegations that African Americans had breached the color line by, for example, physically harming whites or threatening violence against police officers.

The African American novelist Richard Wright, a Mississippi-born and raised migrant to Chicago, captured well the tragic, and extraordinarily consequential, remaking of rough justice in the United States in the first half of the twentieth century. In his 1940 novel Native Son, Wright depicts Bigger Thomas, a young African American murderer created by the squalor, inhumanity, and hopelessness of the racially segregated northern metropolis. Bigger is accused of murdering and raping a young white woman, Mary Dalton. After a manhunt by Chicago police through the black South Side, Bigger engages in a rooftop shootout with police and is wounded and captured. As a mass mob of Chicago whites stands outside the courthouse shouting "Lynch 'im!," the prosecuting attorney, Buckley, argues that Bigger must be sentenced to death to protect white women from black male criminals but also to uphold "sacred law" and its "holy" role as guarantor of social order. Bigger Thomas is rapidly convicted and sentenced to death; the governor of Illinois refuses to intervene to block the execution.

By 1940, the transition in legal systems was largely accomplished throughout the country. Rough justice was enacted no longer through lynching but through legal executions that combined legal forms, symbolically-charged and arbitrary retributive justice, and white supremacy, and through racially-motivated, lethally-excessive urban policing. Having lived as an African American in both the rural South and the urban North, Wright captured well the social experience and rhetoric of this transition. By the last third of the twentieth century, urban African Americans rebelled against the new legal order. Allegations of police brutality sparked extensive riots in Watts in South Central Los Angeles in 1965, Newark in 1966, and Detroit in 1967. At the end of the twentieth century, the acquittal of four white police officers accused of beating African American motorist Rodney King in April 1992 precipitated large-scale riots in Los Angeles and smaller outbreaks throughout North America.

Informal practices of racially motivated, lethally excessive urban policing, carried forth during the transformation of American demography by urbanization and suburbanization in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, have never been systematically addressed, even amid a long line of similar deaths of African American men at the hands of police forces after the turn of the twenty-first century that include Eric Garner, Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri in 2014, Freddy Gray in Baltimore in 2015, and Philando Castile in Falcon Heights, Minnesota, in 2016.

One might hope that America’s racial reckoning during the COVID-19 pandemic might spark a much more systematic examination of how the nexus of race and violence intrinsically links the past and present across American regions and that the senseless deaths of Ahmaud Arbery and George Floyd will hasten much-needed reform of a criminal justice system still beleaguered by a racist past and inequitable present.