Respectability and Remembrance: The Continued Condemnation of Black Resistance

The killing of George Floyd spurred protests in cities across America that have been met with heavy police resistance, and there is no end in sight to the unrest. Amid continuing violence against African Americans at the hands of police and the devastating toll that covid-19 is taking on black communities, the protests have swelled.

In contrast to the relatively relaxed police response to the armed, largely white anti-lockdown protests just a few weeks ago, police reaction to these large, generally peaceful protests has been highly militarized, a dynamic that has led to confrontations and injuries and fueled further unrest, rage and destruction.

As this violence unfolds, many communities remain sympathetic with the protestors, contributing en masse to bail funds for those arrested, while others, including the president, have condemned the protestors as violent, and a third grouprecognizes the righteousness of the protestors' cause but rejects arson, looting and violence: this group sees the violence has distracting from the Black Lives Matter cause.

Condemnation of black violent resistance, and of black radicalism, is not a new phenomenon, nor is the dismissal of black people’s claim for justice if their uprisings or activism do not fit a particular script of nonviolence. This condemnation is further illustrated by popular memory of the civil rights and Black Power movements, which valorizes nonviolence while dismissing, and often simplifying the histories of, groups that supported armed resistance. This problem is rooted in popular narratives of the civil rights movement which dramatically oversimplify what took place. These popular narratives lionize the non-violent protests led by Martin Luther King Jr., while ignoring the limits and failures of this approach that left many demands of the movement for racial equality unaddressed — including police violence. When viewed more broadly, the current protests are a continuation of this struggle for racial justice.

And while King is remembered as the pre-eminent champion of non-violence, popular memory has forgotten that he recognized the limits of a nonviolent civil rights movement, saying that riots were the “language of the unheard,”illustrating the need for more radical resistance when peaceful protests do not suffice.

In fact, the civil rights movement included much debate among activists who grappled over tactics. Stokely Carmichael, later known as Kwame Ture, became frustrated with nonviolence when, despite securing legal rights, black people continued to face police violence, poverty, and incarceration. Nonviolent protest, which had helped achieve voting rights, legal access to public accommodations, and the end of Jim Crow, had proved unsuccessful in solving these problems.

That fueled the rise of Black Power activism, which appealed to African Americans who felt voiceless, especially the economically and politically disadvantaged. And yet, while often remembered, in the words of historian Peniel Joseph, as the civil rights movement’s evil and “ruthless twin,” Black Power did critical work to highlight white supremacy and anti-democratic practices against black people, while also bettering the condition of disadvantaged African Americans.

And yes, the Black Panthers, maybe the most famous Black Power organization, carried weapons, but they also organized free breakfast programs for poor, black children and carried out tests for sickle cell anemia, a blood disorder that almost exclusively affects black people in the United States. The Panthers saw such programs as crucial in serving oppressed communities and providing equal opportunity.

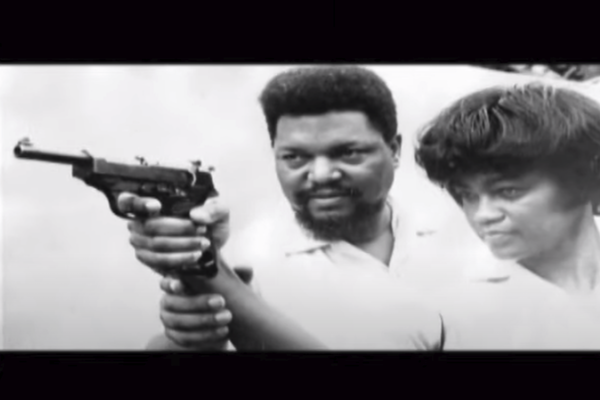

But these efforts have been forgotten because the images of the Panthers remaining in popular memory show them armed, reinforcing white fears of violence. But this ignores that such armed resistance was actually far more about self defense than aggression — something that has been forgotten because, while a number of large-scale episodes of police violence and vigilantism against protestors and activists — Birmingham, Selma, the murders of civil rights activists in Philadelphia, Miss. — are enduring, the day-to-day violence, including police violence, against African Americans, North and South, has been forgotten.

At times, armed self-defense was the only thing that prevented violence against African Americas. One of the most well-known radical activist groups, The Deacons for Defense and Justice, an armed wing of the civil rights movement that existed from 1965 to 1969, openly carried weapons to deter white-on-black violence in Jonesboro, Louisiana. These efforts led to a massive decrease of white attacks on black homes and on civil rights workers. Armed resistance was not only necessary but successful, despite criticisms from whites and moderates. Furthermore, uprisings in Watts in 1965 and across the country in 1968 illustrated the need for more radical resistance. The events of 1965 in Los Angeles are commonly known as the “Watts riots,” consistent with the pattern of using language to contrast insurgent protest as antagonistic to nonviolent protest and therefore, illegitimate. Yet, a nationwide series of riots in 1968 arguably led to the passage of a second major civil rights law, the Fair Housing Act to address the failure of the 1964 legislation to ameliorate urban segregation.

Public memory has continued to deemphasize this radical tradition. While there are at least 40 statues of King across the United States there are fewer than five of Malcolm X, and none of Black Panther leader Fred Hampton, who was shot and killed in his home by the FBI and Chicago police officers. In fact, Hampton’s home was removed from an Illinois African American heritage guide after being deemed too controversial by the Illinois Tourism Bureau.

Major African American history museums, including the Smithsonian Museum of African American History and Culture, portray the Black Power era as one of chaos. This section of the museum is disorganized, difficult to navigate, and accompanied by loud music, signifying a rupture with the preceding narrative. Simply put, Black Power is remembered for not falling in line with a history of respectable nonviolent protest.

Violence has long been a part of civil rights protest going back to the days of abolition because white supremacy is rooted in violence and perpetuated overwhelmingly by law enforcement and white vigilantes with tacit support of legal authorities. This is on display today in the excessive force that has been continuously used against black citizens by police and which resulted in George Floyd’s death. Countless videos of unarmed, peaceful protestors or journalists being pepper sprayed, shot with rubber bullets or, driven into by a police SUV have been shared on television and social media since the protests began.

But actually addressing the full depth of racism and white supremacy in America requires understanding the limits of the non-violent civil rights movements, and the necessity of armed self-defense for African Americans against the violence perpetrated or instigated by whites — including the police — throughout American history.