Woody Guthrie's Communism and "This Land Is Your Land"

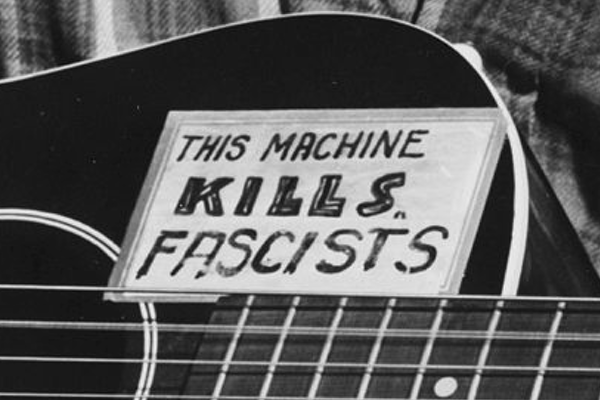

Just before her high wire performance at the 2016 Super Bowl, Lady Gaga sang the opening lines of Irving Berlin’s “God Bless America,” before segueing into Woody Guthrie’s “This Land is Your Land.” That Guthrie’s song was written in angry response to Berlin, and that its incorporation into such a corporate spectacle likely would have caused Woody no small amount of distress, appears to have been something Gaga was unaware of. Such confusion is not especially unique. The song has been mired in ambiguity for decades.

Woody Guthrie’s inspiration for the song came as he traveled from California to New York in the winter of 1940. At the time there was no getting away from Berlin’s song, which was everywhere on the radio, sung by Kate Smith — someone back in the news, not for that composition, but for singing songs with racist content. When Guthrie finally reached New York he sat down and wrote, “God Blessed America for Me,” which would become “This Land is Your Land” — with its melody taken from the Carter Family’s “When the World’s on Fire.” Guthrie’s song, rather than extoling God’s special relationship with the United States, asked how it could be that He blessed a country where people were standing in the relief lines, hungry and out of work. It was, to say the least, not a barnstormer of unabashed patriotism.

Guthrie & the Communist Party

To the degree people know the politics of Woody Guthrie today he is thought of as an advocate for social justice, with a degree of association with mid-century US communism, but mainly a free spirit who travelled among and gave voice to the dispossessed in the United States. The matter of whether or not he was an actual member of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA) has long been debated, with the consensus being he was simply not party material.

On a general level this is correct, but not wholly so. That is because not only was Guthrie a close supporter of the party, there is strong evidence he was a member of the group for a short time in the early 1940s, before being dropped because of discipline issues. Not only that, he unsuccessfully reapplied to the group during World War II, but was rejected, according to his second wife Marjorie Guthrie, something she revealed in Oregon’s Northwest Magazine in 1969.

This is different from the prevailing view, most forcefully argued in Ed Cray’s Ramblin’ Man: The Life and Times of Woody Guthrie, which cites numerous friends and former comrades who claim Guthrie was not, and could never have been, in the Party. Cray however, contradicts himself in a footnote:

[The writer] Gordon Friesen, on the other hand, maintained that Guthrie was a member of the Communist Party briefly in 1942. It ended sometime in the summer months. Friesen wrote, after Guthrie was summoned by “his organizer” to “a branch meeting” in Greenwich Village. Guthrie was to answer charges of lack of discipline… He had pledged to appear at a certain Village street corner to sell Daily Workers and then had failed to show up.

Cray found this anecdote in a letter from Friesen to historian Richard Reuss, the author of the seminal work, American Folk Music and Left-Wing Politics: 1927-1957.

What is notable about this story is that it is one that had been told elsewhere, by music critic Robert Shelton in his biography of Bob Dylan. Shelton says Friesen wrote to him directly, remarking on how badly the CPUSA treated artists, citing Guthrie as an example, “I remembered Woody showing me a letter from his section organizer in the Village ordering him to appear to answer charges for ‘lack of discipline’ because he had failed to show up at a certain corner to sell the Daily Worker.”

Both these stories, in turn, align with Pete Seeger’s recollections. According to Seeger, who spoke with Robert Santelli for his book, Hard Travelin: The Life and Legacy of Woody Guthrie, “Woody considered himself a communist. Was he a member of the Party? Not really.” According to Seeger, “The Party turned him down. He was always traveling here and there. He wasn’t the kind of guy you’d give a Party assignment to. He was a valued fellow traveler.” Seeger, however, continues:

On the other hand, Sis Cunningham, who was a much more disciplined person than either me or Woody, was in a Greenwich Village Branch of the Party. She got Woody in. She probably said, I’ll see Woody acts responsibly.’ And so Woody was briefly in the Communist Party.

Sis Cunningham, it should be noted, was married to Gordon Friesen, and was one of the Almanac Singers in New York before World War II, along with Guthrie, Seeger, Bess Lomax, Millard Lampell and others. That aside, Seeger’s characterization matches with the information above.

Dues paying or not, Guthrie was a committed partisan of the CPUSA. As Los Angeles Party leader Dorothy Healey put it, “If he wasn’t a Party member, he was the closest thing to it.” This is important not only factually, but for what it says about the attention the FBI directed at him. The Bureau tracked Woody Guthrie for over three decades, compiling files adding up to 593 pages. If his association with the Party was as tenuous as some have claimed, then the FBI was seriously off track in the attention they gave him. From their perspective, pursuing people with serious ties to US communism made sense. Which is not to say it was just. Guthrie was not breaking any laws or otherwise engaged in activity meriting such attention. In fact it is abominable that the FBI continued to monitor him for years after his diagnosis with Huntington’s Chorea, as he was losing his ability to walk and even speak.

A Song With Many Meanings

Woody Guthrie met the Communist Party in Los Angeles in 1939, while working at Radio Station KFVD. There he met Ed Robbin, a writer for Peoples World, the party’s West Coast newspaper. One of the first things Guthrie did after meeting Robbin was to write a song about Tom Mooney a labor organizer who had been imprisoned for allegedly bombing a “Preparedness Day” parade held in preparation of the US entering World War I. Guthrie’s first partisan act in that respect was to write “Tom Mooney is Free,” on the occasion of Mooney’s release. A greater example of his partisanship came in the lyric, “Why Do You Stand There in the Rain?” which he wrote in response to Franklin Roosevelt’s scolding of a youth rally — that included communists — held soon after the USSR went to war against Finland. Among other things the lyrics take a strong anti-war stand consistent with the CP’s slogan at the time, “The Yanks Aren’t Coming” — a position they held during the non-aggression pact between Germany and the USSR. Guthrie, in other words, was already incorporating the political line of the Communist Party into his lyrics when he sat down at actor Will Geer’s house in New York to write what would become “This Land is Your Land.”

In that respect, in order to better understand the song, one needs to understand the peculiarity of the CPUSA under the leadership of Earl Browder. A major slogan of the CP when Woody came on the scene was, “Communism is 20th Century Americanism.” That slogan was in keeping with Browder’s attempt to create a big tent for communism in the United States, steeped in anti-fascism and social-democracy. That the slogan was a mash-up of communism and US exceptionalism helps explain why Guthrie’s song stops in New York, rather than going on to the wider world — communism, after all, was supposed to be internationalism. Browder and the CP’s approach to communism was far more U.S.-centric than internationalist —except of course when it came to supporting the geopolitical dictates of the Soviet Union. All of which explains the orientation of the song.

Depending on the listener, “This Land is Your Land” can be heard in different ways. Guthrie most likely intended it as a call to move beyond private property, and toward a greater equality and common humanity. Notably the lines usually excluded, talk about encountering a sign reading, “No Trespassing,” while the other side of the sign, “didn’t say nothing.” — that being the sign that was “made for you and me.”

More moderately it can be heard as a liberal-secular hymn, in which all people ought to share in the country’s bounty. That is why Pete Seeger and Bruce Springsteen could safely perform it at Barack Obama’s first inaugural celebration.

Alternately still, and not without basis, it can be heard as a proclamation of American chauvinism — in fact the song has been criticized as justification of manifest destiny and even the theft of native lands because of its lines extolling the US landscape achieved through no small amount of blood and conquest.

Such debate will likely never get fully resolved. However, given the politics of its author, and in the interests of showing a little respect for the dead, it would seem a modest request — all due respect to Lady Gaga — to ask that the song not again be sung as part of a medley with “God Bless America.”

Author Update (10/9/2020): After this article published Ronald Radosh helpfully reminded me that he too discussed Guthrie’s membership with Gordon Friesen, this in 1970. In a paper published in 2015 Radosh wrote.

[H]is friends Gordon Friesen and Sis Cunningham, the founders in the 1960s of Broadside, and former members of the Almanac Singers, told me in a 1970s interview that Woody was a member of the same CP club as they were, and was regularly given a stack of The Daily Worker which he had to sell on the streets each day.

What is noteworthy in Radosh’s account is the inclusion of Friesen himself as being a member of Woody’s club, something not in the accounts by Robert Shelton or Richard Reuss, discussed above.

Friesen was always cagey about his Party affiliation, even later in life. Thus in his autobiography, written jointly with his wife ‘Sis Cunningham, we get the following exchange.

Interviewer: You were both members of the Communist Party then?

Sis: We sure were.

Gordon: I’m not sure I was actually a member.

Sis: Maybe I shouldn’t have said that. I thought you were maybe you weren’t. I thought I was.

As I point out in the Folk Singers and the Bureau, Friesen’s circumspection— and the awkward attempt at walk back in the above exchange — is likely a result of his having given a statement to the authorities in the course of a Hatch Act investigation, swearing he was not a member of the Communist Party – information that is contained in his FBI file. In other words, admitting he was in the Party, after claiming otherwise, could make him vulnerable to criminal charges. All of which is testimony to the long reach of the Second Red Scare.